1960s—More Talk than Peace

Widely hailed as one of the outstanding professional diplomats of his generation, Philip C. Habib (1920-1992) served as deputy assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific affairs from 1967 to 1969. He later served as ambassador to South Korea (1971–1974), assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific affairs (1974–1976), and under secretary of State for political affairs (1976–1978). After retiring from the Foreign Service, Ambassador Habib was twice recalled to duty, first as a special adviser and then, in 1981, as a special envoy to mediate the Lebanese civil war.

In this section of his ADST oral history, Amb. Habib recalls his role on the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Talks, which began in 1968 and finally concluded in 1973 with the agreement on ending the war and restoring peace in Vietnam.

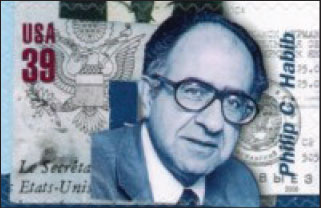

Philip C. Habib was one of six distinguished American diplomats honored by the U.S. Postal Service with a commemorative stamp in 2006.

From our standpoint, we were willing to go for a total bombing halt, but we wanted to get a proper negotiation going including the South Vietnamese. We had South Vietnamese liaison guys there in Paris. But the actual negotiations were between us and the North Vietnamese.

We had two levels of negotiations. For the formal talks every Thursday, we would convene at the Majestic Hotel at Avenue Kléber. The delegation would file into this magnificent conference hall, and we’d sit there and read statements to each other, and go out and talk to the TV cameras, and go back to the office and meet again the next Thursday.

Well, that went on for a while, and obviously we weren’t going to do anything under that spotlight, so we had a couple of private meetings, and then we set up the formal secret negotiations. They had a safe house, and we had a safe house. Nobody knew, nobody had a clue where they were. They knew that something was wrong, but couldn’t figure out what.

I remember one CBS reporter said, “Now we’ve figured it out, you’re meeting on a houseboat on the Seine.” Yes, that’s right, on a houseboat, you get a rowboat and follow us out. They never discovered it, and why? We ran it, we were professionals. Nothing ever leaked from them, or from us. We had a whole series of good meetings.

Cy Vance and I had carried on most of the secret negotiations. We would bring Averell Harriman in for the key ones. Cy and I had meeting after meeting, and a couple of times I had meetings alone, at the last stages when we were drafting terms in getting the agreement on the shape of the table. All that was done in that period under the secret negotiation.

Harriman, right, head of the U.S. delegation, and Cyrus R. Vance, left, leaving the Paris Vietnam peace talks on Oct. 24, 1968.

Pierre Boulat / Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

From May, June, July, August, [the North Vietnamese] wouldn’t give a thing. We had been pressing them: What would we get if we gave a total bombing halt? For the total bombing halt we wanted, specific things had to happen.

Finally, all of a sudden one day, the head of their delegation, a member of the Politburo, said to Harriman and Vance, “If we do so and so and so, will you stop the bombing?”

At that point, you knew you had it. It was just that stubbornness and reading reams of propaganda bullshit, even in the secret talks. They finally agreed to what we needed, and what we wanted, and the deal was cooked in October 1968.

And then something happened. ... before the election. Somebody got to [South Vietnamese President Ngyuen Van] Thieu on behalf of Richard Nixon and said, “Don’t agree, come to Paris.”

It was done right here in Washington. A Republican went to a famous woman called Anna Chennault. Anna Chennault went to the Vietnamese and told them: “We’ll get a better deal under Nixon.” So Thieu refused to accept the agreement and sent a delegation to Paris.

Clark Clifford was fit to be tied. Harriman was about to climb the wall. Well finally, of course, the election was held and Humphrey lost. I’m convinced that if Hubert Humphrey had won the election, the war would have been over much sooner.

Instead, a new group came along. You couldn’t get the thing cranked up until after the inauguration, which meant you marked time until January 1969.

Meanwhile the [South] Vietnamese agreed to come, so they formed their delegation, and the Viet Cong came with their delegation. People said it took us three months to decide on the shape of the table, but that was a bunch of shit. We knew what shape the table was going to be from the beginning; it was going to be a round table. It was the only way you were going to solve the problem.

We knew that, but we had to go through this whole routine of satisfying the South Vietnamese, and beating down the arguments of the North Vietnamese who wanted the Viet Cong as an equal delegation. They talked about a four-party negotiation, and we talked about an “our side, your side” negotiation. We finally resolved the problem by a round table. We knew we were going to do that. But you couldn’t solve anything when you didn’t have delegations.

Clark Clifford was fit to be tied, and Averell Harriman was about to climb the wall.

–Philip Habib

The new administration appointed Cabot Lodge as head of the delegation and, of course, he had a so-called number two called Walsh, a lawyer from New York who didn’t know anything about the problem. He was a Republican lawyer from New York who was in the early Nixon administration.

Cabot came and we began sort of floundering around. At that point Henry Kissinger entered the negotiations by deciding that he’s going to run the secret negotiating. He had Dick Walters, who was then the military attaché, set up the negotiation, and said nothing to us. Henry lacked confidence in the secrecy of the Foreign Service.

[Kissinger] had with him Winston Lord, Tony Lake, and this character, Walters. None of them knew anything about anything at that point compared to us. …