The FRONT-Line Initiative: Combating Transnational Criminal Organizations

Transnational street gangs are a growing problem for communities and law enforcement across the United States. State’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security is part of the solution.

BY CHRISTOPHER “KAI” FORNES

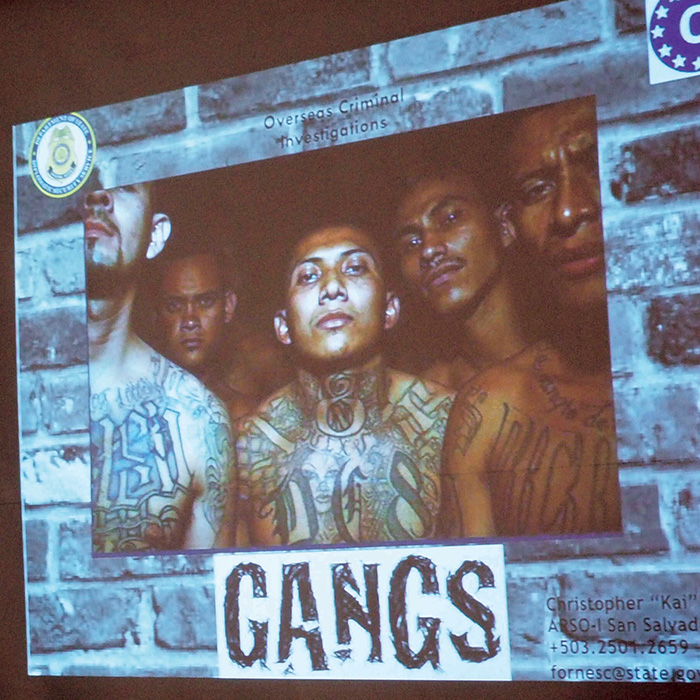

Special Agent Kai Fornes presents the San Salvador enhanced gang vetting process at the 2017 inaugural FRONT-Line Workshop in San Salvador, with a graphic from the presentation.

U.S. Department of State

Local and regional street gangs have always been a problem for local police departments. But, as Homeland Security Investigations Special Agent Angel Melendez and U.S. Marshall John Gibbons note in their recent article for The Police Chief magazine, “The Perfect Storm: The Convergence of Gangs and Transnational Crime,” the past few decades have seen the emergence in American cities of gangs whose criminal activity takes place in more than one country.

These transnational gangs, which often have sophisticated networks and exploit smuggling routes used to bring narcotics, people and proceeds across international borders illegally, are a growing challenge for local communities and for law enforcement across the United States. In a February 2017 Presidential Executive Order on Enforcing Federal Law with Respect to Transnational Criminal Organizations and Preventing International Trafficking, the Trump administration mandated an increased focus on combating criminal gangs and cartels.

Take, for example, La Mara Salvatrucha. Better known as MS-13, this notoriously violent gang that was designated a priority in October 2017 by the Department of Justice’s Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces tops the list of threats for many major U.S. cities. The FBI estimates that there may be up to 10,000 MS-13 members living in the United States, many of whom emigrated from Central America. Although the gang formed in Los Angeles decades ago, its leadership is based in the “Northern Triangle”—El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras—where U.S. law enforcement has no jurisdiction. This makes it very difficult to combat MS-13’s influence and activities in the United States, which is why preventing members and affiliates from entering the United States in the first place is critical.

This is where the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service comes in.

A New and Exemplary Initiative

As the law enforcement and security arm of the U.S. Department of State, DSS partners with law enforcement in foreign countries to investigate crimes that affect U.S. citizens and national security, and trains our international counterparts to assist in those efforts. Combating transnational criminal organizations, including international gangs, is one of its top priorities. The most widely represented U.S. law enforcement agency around the world, DSS has more than 2,100 special agents serving at 275 U.S. embassies and consulates in 170 countries, as well as 29 domestic offices across the United States.

In August 2017, as part of the effort to combat gang-related transnational crime, DSS and the State Department Bureau of Consular Affairs at the U.S. embassies in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras launched an enhanced gang vetting program to identify and block legal travel to the United States by gang members called the Fraud Reduction Operations in Northern Triangle (FRONTLine) initiative. The initiative was first implemented in San Salvador. In 2017 El Salvador’s annual homicide rate was 60 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, placing it second on the list of countries outside of war zones with the highest homicide rates, according to InSight Crime. Many of the homicides and violent crimes in the country are attributed to gangs, which the Salvadoran government has been aggressively confronting.

Though the majority of gang members who enter the United States do so illegally—without a visa and without inspection at a port of entry—many also attempt to obtain visas through the application and interview process at a U.S. embassy or consulate outside the United States. Significantly, as border security enhancement efforts to curb illegal immigration at the southern border itself show more success, DSS and consular fraud prevention investigators have observed an upward trend in gang members attempting to manipulate the visa process.

The U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act is an excellent tool for preventing gang members from entering the United States on valid U.S. visas, but it is only effective when consular officers adjudicating visa applications have evidence of an applicant’s gang affiliation. According to Section 212(a)(3)(A)(ii) of the Act, an applicant is ineligible for a visa when a consular officer has reason to believe that the applicant is coming to the United States solely, principally or incidentally to engage in unlawful activity. Visa applicants who are affiliated with gangs can be found to be ineligible for visas to travel to the United States under this section; it does not require a criminal conviction, and there is no waiver available for this inadmissibility.

The FRONT-Line Process

Since, however, it is extremely unlikely that gang members would disclose any information on a visa application that would bar them from entering the United States, such as their gang affiliation or criminal history, additional on-the-ground resources for fully vetting those applicants are needed.

The FRONT-Line initiative’s enhanced gang vetting program provides those essential tools and training. The program includes an increased focus on visa applicants in categories particularly susceptible to gang infiltration; it provides training for consular staff and support personnel at the three U.S. embassies in the Northern Triangle; and it offers a regional training course focused on interview techniques.

DSS-trained Salvadoran law enforcement and immigration officials are another key element in combating transnational crime and document fraud.

Consular officers at embassies in the Northern Triangle first assess every visa application. If the assessment indicates possible gang affiliation, consular officers refer the application to the consular section’s fraud prevention unit (FPU) for investigation. At the same time, the DSS assistant regional security officer-investigator (ARSO-I) at the embassy investigates the visa applicant’s criminal history and background with local authorities. Once these checks are completed, FPU personnel interview the visa applicant.

If the investigation yields evidence that the visa applicant is most likely affiliated with a gang, or if there is evidence that an applicant has provided false information on a visa application, the ARSO-I will also open a visa fraud criminal investigation.

Several recent applications flagged by the FRONT-Line vetting process have led to investigations that uncovered sophisticated document fraud. These investigations suggest that those attempting to obtain a U.S. visa with falsified documents have detailed knowledge of the visa adjudication process, and are coordinating efforts among local MS-13–affiliated gang members to provide doctored court records covering up more serious crimes and excluding the names of other gang members implicated in those crimes. In other cases, the ARSO-I investigative team has uncovered gang members using false or stolen identities to manipulate both the Salvadoran and U.S. immigration systems.

According to a recent internal review at Embassy San Salvador, the initiative has already proven to be 87 percent more effective in identifying gang members and gang affiliations in the United States and overseas than previously used vetting processes.

Host Nations Partnerships

The cachos (El Salvadoran slang for horns) that hang on the wall of the ARSO-I/Fraud Prevention Unit in San Salvador are a reminder of the significance of the gang vetting efforts. The horns, one of the many symbols used by MS-13, have been painted with graffiti and other adornments associated with the notorious gang.

Courtesy of Kai Fornes

While FRONT-Line gives the embassies’ ARSO-Is and FPUs additional resources and techniques to identify and deny visas to gang members who apply for them, host-nation governments also play a critical role in these efforts. DSS special agents are the senior U.S. law enforcement officials at all U.S. embassies— including in San Salvador, Guatemala City and Tegucigalpa—and this has allowed DSS to foster longstanding, close relationships with local law enforcement and immigration authorities. In addition, DSS placed an ARSO-I at each of the embassies to support investigations and national security concerns that affect not just the United States, but the host countries as well.

A key resource for ARSO-Is and FPUs in the Triangle is a border intelligence fusion center known as the Grupo Conjunto de Inteligencia Fronteriza, which collects and develops regional criminal intelligence and serves as an operational coordination and collaboration center for regional transnational law enforcement initiatives. This center was established by the Salvadoran government in December 2017 after the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs began a joint initiative with the government to better screen incoming migrants for gang affiliations at the southern border of the United States.

The GCIF is preparing to receive personnel soon from Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico, allowing it to expand its coverage. The GCIF is an integral part of the ARSO-I and FPU’s enhanced gang vetting process because it incorporates criminal intelligence information from the FBI, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and partnering foreign law enforcement institutions. The ARSO-I and FPU use these multiple sources of information during the visa adjudication process.

DSS-trained Salvadoran law enforcement and immigration officials are another key element in combating transnational crime and document fraud. For several years, every new Salvadoran police officer and immigration official has received intensive training on how to spot falsified travel and identity documents.

DSS signed agreements with the governments of El Salvador and Guatemala establishing special investigative units of vetted national police officers who work with embassy ARSO-Is to conduct visa fraud investigations. When visa applicants omit disqualifying gang affiliation information in the visa adjudication process, they commit fraud.

As a result of the ARSO-I’s continued collaboration with the San Salvador Attorney General’s Office, it is now a crime in El Salvador to present a false document when applying for a U.S. visa. Also, over the last several months, the ARSO-I has been working with the AGO to explore new ways to prosecute gang members identified by the enhanced gang vetting process. In March the AGO agreed to serve as the primary venue for all cases related to gang affiliation visa fraud, a significant development for the U.S.- Salvadoran relationship and for DSS’ work to combat transnational gangs overseas.

Supporting U.S. Gang Investigations

One of the greatest contributions DSS makes to the U.S. law enforcement community is providing investigative information and intelligence gained by working with our law enforcement partners overseas.

In January the DSS Overseas Criminal Investigations Division chief—who oversees the ARSO-I program and the ARSO-Is posted in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras—briefed the gang task forces of Nassau and Suffolk Counties in Long Island, New York, on the FRONT-Line initiative. They discussed how information gleaned from the vetting process and investigations can assist state and local law enforcement when they are working on cases that may involve transnational criminal gangs. A week after the meeting, Suffolk County law enforcement officials used the information provided by DSS to identify an alleged MS-13 suspect who was wanted in Maryland and hiding in Suffolk County.

The FRONT-Line effort in the Northern Triangle serves as a standard for how to combat violent criminal gangs at home. Identifying, disrupting and dismantling transnational criminal gang activity is only possible through collaborative efforts both at home and abroad. DSS and the rest of the State Department will continue to work hard to deter legal entry of potential gang members into the United States, and to support U.S. law enforcement agencies combating violent gangs inside the United States.