Remembering a Born Diplomat and Consummate Professional

BY JAMES T.L. DANDRIDGE II

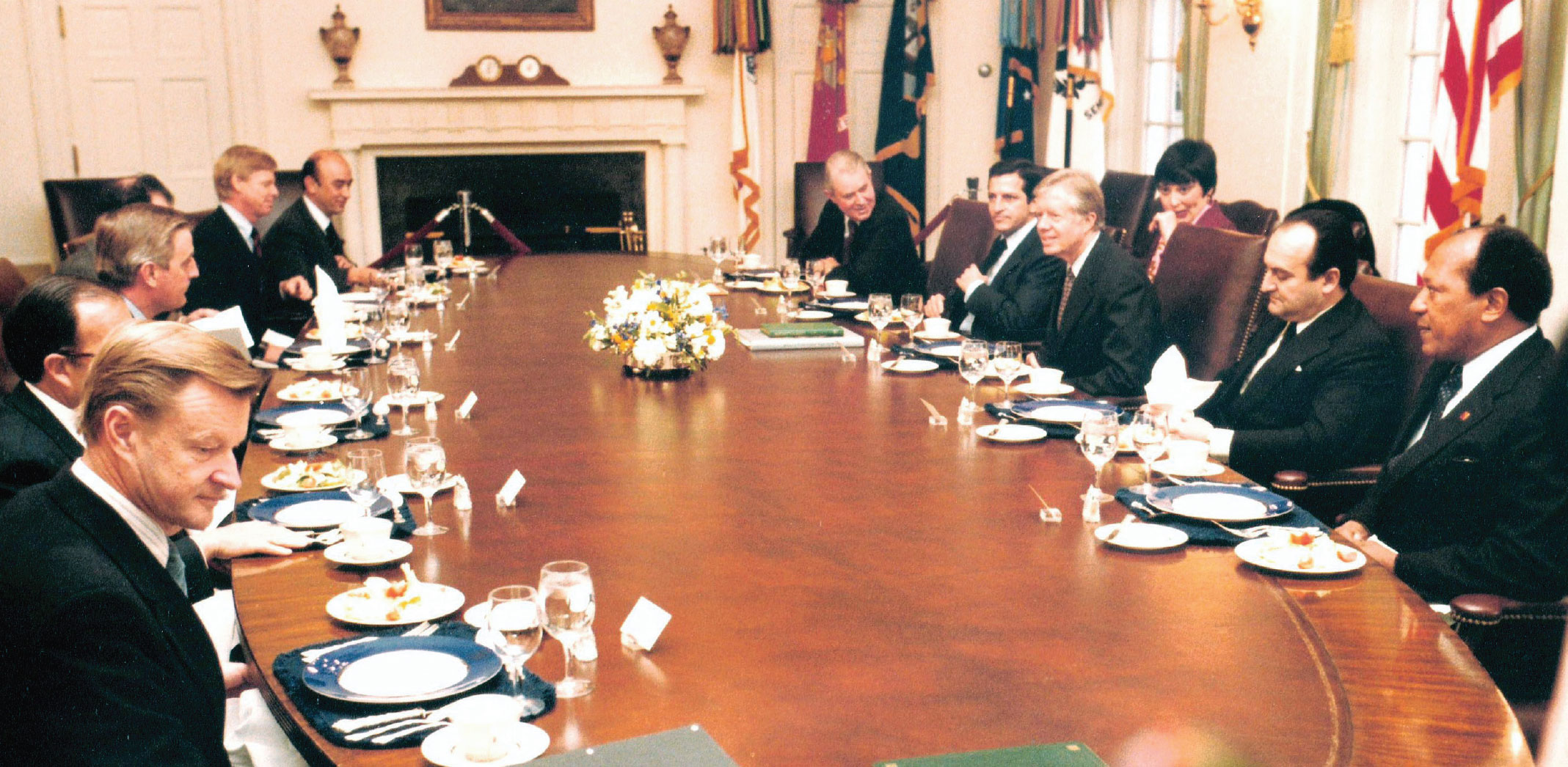

Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Terence Todman, far right, at a Cabinet meeting with President Jimmy Carter, third from right, and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, sixth from right, at the White House during the Panama Canal negotiations in 1977.

Courtesy of James Dandridge II

Career Ambassador Terence Alphonso Todman died on Aug. 13, and his life was celebrated in a memorial service on Aug. 28 in the George C. Marshall Center at the United States Department of State.

Ambassador Todman’s service to his country spanned almost 50 years, and he continued to support the execution of U.S. foreign policy after his retirement. He was the 1997 recipient of the Director General’s Cup for the Foreign Service in recognition of his unceasing promotion of the U.S. Foreign Service as a diplomat in retirement.

Many knew Amb. Todman, but even more had heard of him APPRECIATIONas a result of his diplomatic excellence. He was a born diplomat, a consummate professional who was dedicated to supporting the execution of American foreign policy. Unarguably one of America’s most effective Foreign Service officers, he was chief of mission at six embassies on three continents, and earned the highest rank in the Foreign Service, career ambassador.

The American Heritage Dictionary characterizes diplomacy as tact and sensitivity in dealing with people. A major element in Amb. Todman’s success was his respect for individuals and cultures; he could deal with anyone, keeping his mind open and his judgments to himself. Also, he understood that governments were made up of people—individuals, with all their prejudices, preconceptions and ambitions. He always worked the person, not the agency, office or organization. And, above all, it was never “about me.”

A Born Diplomat

Ambassador Todman with President George H.W. Bush at a White House reception.

Courtesy of James Dandridge II

Born in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, on March 13, 1926, Terence Todman exhibited early signs of concern for others, especially for the plight of his Caribbean neighbors in Haiti. This was the beginning of the development of a desire to prepare himself to do something for the region. He undertook to learn to speak Spanish and commenced his university studies in Puerto Rico. Recognizing this budding interest in reaching out to help his fellow man, his mother gave him one indelible piece of counsel: “Don’t get involved in Virgin Islands politics.” And by extension, he carried that advice through life, recognizing the need to be politically aware while not becoming politically involved.

Amb. Todman was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1945 and was commissioned into the officer corps and assigned to General Douglas McArthur’s U.S. military government staff in Tokyo. He plunged into exercising his diplomatic skills in dealing with the Japanese populace, teaching himself enough of the language to be professionally conversant in his areas of responsibility. He was already developing skills that would later serve him so well.

Amb. Todman quickly discovered that there was a gulf of misunderstanding between Japanese and American citizens and, as a result of acquiring proficiency in Japanese, his third language, he was able to serve as a cultural bridge to help neutralize the misconceptions and misinformation each society held about the other.

Many are aware of the role that Amb. Todman played in desegregating the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute in 1952 when he entered the Service. But few know that his Army assignment to Tokyo had come as a result of his having “stirred up problems” over the lack of access for minority officers to the officers club and swimming pools at the U.S. Army Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland, where he was trained as an ordnance officer.

An Unequaled Career

Ambassador and Mrs. Todman arriving for the ambassador’s 85th birthday gala on March 11, 2011, at the Frenchmen Reef Marriott Resort Hotel in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Courtesy of James Dandridge II

In 1952 Amb. Todman embarked on a Foreign Service career that is unequaled by most. His postings included India, Lebanon (for Arabic language training), Tunisia and Togo (as deputy chief of mission). Then he took up three consecutive ambassadorships, in Chad, Guinea and Costa Rica. After serving as assistant secretary of Western Hemisphere affairs, he held three more ambassadorships, to Spain, Denmark and Argentina. In addition to Spanish and Japanese, Amb. Todman showed a proficiency for difficult languages by learning Arabic and Hindustani.

If there were to be a Todman-100 course on how to excel in diplomacy, one of the things it would highlight is his demonstration early on that there is no such thing as a “small post.” After a stint as DCM, with extended time as chargé at an African post, he was selected as chief of mission to what were perceived as obscure posts in Africa. In each, he displayed outstanding skills in focusing U.S. foreign policy on issues that had continental reverberations.

Based on insights honed during earlier assignments with various United Nations Trustees Committees, he was able to steer the formulation of U.S. foreign policy toward actively promoting the democratization of newly independent countries, rather than simply following the Western colonial powers or acceding to the influences of Cold War antagonists on the continent. He proved that size does not matter in diplomacy; proactive leadership in policy articulation is what counts.

Amb. Todman considered himself a professional who served at the will of the president, regardless of political party affiliation. He developed strong professional and personal relations with both Republican and Democratic administrations and faithfully supported the policy objectives of each. In this regard, he took his mother’s counsel beyond the confines of the U.S. Virgin Islands. In fact, he never short-circuited the system by claiming residence in a mainland state for federal voting privileges.

The Duty to Give Counsel

Terence Todman and Henry Kissinger in conversation.

Courtesy of James Dandridge II

On more than one occasion, Amb. Todman strongly presented advice to the department, even when it ran counter to Washington thinking. He took the position that as a career diplomat, he had the duty to offer the best counsel in the furtherance of the execution of U.S. foreign policy.

On one occasion, while working on certain issues as COM in Madrid, Amb. Todman encouraged Secretary of State George Shultz to visit Spain. Todman flew to Paris to meet the Secretary prior to the visit and, on reading the Secretary’s briefing book, was astonished to find that Washington had turned his recommendations on their head.

As Amb. Todman tells the story in his oral history: “So when he got on the plane the next day, I said, ‘Mr. Secretary, they have set you up for disaster. If you follow what this book says, things will go very bad for your visit and for our relations.’

“‘Then what should I say?’ Shultz asked.

“‘Go back to what I wrote,’ I said. And we went over again what I had said.

“‘Well, okay, [if] you insist on this, I will do it,’ Shultz replied. ‘But, if it doesn’t work, it is your neck.’

“‘Of course,’ I said. ‘If I give you bad advice then I shouldn’t be here.’

“The people back in Washington who felt they knew all about it had just turned things around. Fortunately, Shultz followed [my] advice, and things went very well. At the end of it, Secretary Shultz said it was one of the best trips he’d taken.”

Amb. Todman also recognized the essential role of the Foreign Service family. On one occasion, he took his younger son with him to a civic organization where he was scheduled to speak. Explaining all of the parameters of the event on the way to the program, he sought his son’s advice and feedback on the planned presentation. When introduced to speak, Amb. Todman announced that his son had contributed to the preparation of his presentation; and, to his son’s utter surprise, he introduced the young man to make the presentation in his stead.

As his sons eulogized Amb. Todman at his funeral in St. Thomas on Aug. 23, they eloquently summed up their father’s life mission by reading lyrics from the last verse of “The Unreachable Star” in Joe Darion’s musical, Man of la Mancha. In this song, Don Quixote explains his quest and the reason behind it:

And I know if I’ll only be true, to this glorious quest,

That my heart will lie peaceful and calm,

When I’m laid to my rest ...

And the world will be better for this:

That one man, scorned and covered with scars,

Still strove, with his last ounce of courage,

To reach the unreachable star.

Read More...

- Virgin Islander Terence Todman, ambassador extraordinaire (Virgin Island Daily News, March 11, 2011)

- Being Black in a “Lily White” State Department (Excerpts from Terence Todman Oral History with ADST)

- Celebrating the Life of Career Ambassador Terence A. Todman (FSJ, October 2014)

- Terence A. Todman, U.S. Ambassador to Six Nations, Dies at 88 (Washington Post, August 2014)

- 10 Things You Didn’t Know About U.S. Ambassador Terence Todman (AFK Insider, September 2014)