The Achille Lauro Affair, 1985

Reflections

BY TOM LONGO

The Achille Lauro

D.R. Walker / CC BY-SA 3.0

In late 1985 Italy was crucial in NATO negotiations with the then-Soviet Union on the issue of Intermediate-range Nuclear Force missiles in Europe. Essential was Italy’s commitment to deploy some INF (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force) missiles on her soil for NATO to counter the Soviets’ installation of SS-20 missiles in Eastern Europe. Italy’s site for the missiles was a former abandoned World War II air base in southeastern Sicily near the town of Comiso.

At the time I was head of the State Department’s Italy desk. As such, I was the everyday point person in Washington for both U.S. Embassy Rome, headed by Ambassador Maxwell Rabb, and the Italian embassy in Washington under Ambassador Rinaldo Petrignani.

In October 1985 four Palestinian terrorists hijacked the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro in the Mediterranean. They killed an elderly American passenger, Leon Klinghoffer, and threw him and his wheelchair overboard. Days later the ship docked in Egypt, and the hijackers and their ringleader were being flown to safety aboard an Egyptian state airliner when, with no advance notice to the Italians, U.S. Navy jets intercepted the airplane over the Mediterranean and forced it to land at an Italian NATO base in Sigonella, Sicily, some 100 kilometers north of Comiso.

Moments of high drama followed in Washington. I hurtled into the State Department at night to interpret on the telephone between then-Secretary of State George Shultz and his Italian counterpart, Giulio Andreotti, and then at the White House between President Ronald Reagan and Italian Prime Minister Bettino Craxi.

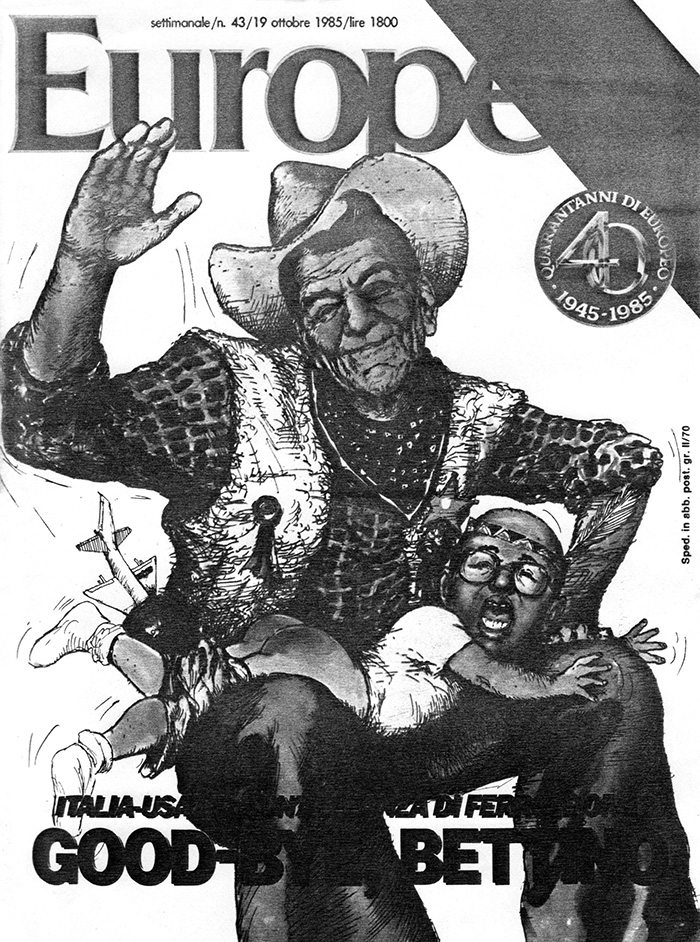

“Good-Bye Bettino.” Reagan spanks Craxi on the cover of a leading Italian newsweekly. Such polemics roused Italy’s democratic parties to fear and anger and encouraged the Communist Party of Italy to try to seize the moment.

Courtesy of Thomas Longo

At the White House I helped to defuse an extremely tense situation at Sigonella, where American commandos and Italian Carabinieri surrounding the Egyptian airliner containing the hijackers were brandishing weapons around each other. The United States had sent the commandos to Sigonella to grab the hijackers and fly them to the United States for prosecution since they had killed a U.S. citizen.

Citing constitutional and legal reasons—since the ship was Italian and at Sigonella the culprits were now within Italian territorial jurisdiction—Craxi refused, begging Reagan’s understanding. I can still hear Craxi’s voice quavering at the prospect of Americans and Italians shooting at each other on the runway. Reagan and Craxi agreed the Italians would assume custody pending a legal extradition request from Washington through diplomatic channels. The issue was calmed for the moment.

More than just interpreting, at the White House and afterward I explained to the Americans the stress and fear in Craxi’s voice and the political backdrop in Italy. There was another mess a few days later when the Italians, for mysterious reasons, let the ringleader, Abu Abbas, go. (Abbas masterminded the plot but was not one of the four actual hijackers on the ship, whom the Italians did prosecute.) Everyone from the president on down was white-hot furious. The Italians reciprocated in kind and both countries embarked on ascending spirals of bitter rhetoric.

There was a real risk that events would spin out of control so as to give an unprecedented political opportunity to the large pro-Soviet Italian Communist Party, whose leadership was salivating at the prospect. And this just as Italy’s willingness to host U.S. medium range nuclear missiles on her soil (ironically, just a short distance from Sigonella) was absolutely critical to the later success of INF negotiations with the Soviet Union.

I had excruciating conversations with the anguished Italian Ambassador Rinaldo Petrignani. Other doors in town were totally closed to him. Extraordinarily, the ambassador asked me directly about the acceptability of certain top Italian political figures to Washington. I had been told only to listen and report back what Petrignani had to say, and I was on the spot to reply. I said I was without instructions but, speaking personally, I was sure the United States would respect whatever leadership decisions sovereign Italy made.

I reported to superiors the desperation Amb. Petrignani’s inquiries reflected, that one sovereign NATO ally would seek pre-approval of another for his country’s internal leadership choices. The drama helped me make the case with my superiors that we had other enduring, especially NATO, interests with Italy, and that we should not allow our justified anger “to throw the baby out with the bath water.”

As an Italian-American boy from Boston and the grandson of immigrants from Sicily, the Italy desk job was especially meaningful for me. I approached it with humility. Helping resolve the Achille Lauro crisis brought a special sense of fulfillment. n