Life After the Foreign Service—What We Are Doing Now, Part II

The May Foreign Service Journal’s focus was “Life After the Foreign Service.” We began preparing that issue in January, with a broadcast message to retired and former members of the Foreign Service requesting input on the “afterlife.” We asked AFSA members to reflect on what they wished they had known earlier about retirement, and what advice they would give their younger selves on planning for it. We also asked what they wish they had known before joining the Foreign Service. And we invited them to tell us about their interesting post-FS lives, including advice for others who may want to take a similar path.

The response was quick and abundant. We received nearly 50 thoughtful essays—far too many for one issue. We published 22 in May, and present the remaining 25 in this edition. Like the first batch, this collection is full of interesting stories. Retirees and prospective retirees alike will appreciate the great variety of paths taken by their colleagues, as well as the hard-won insights and useful advice offered here.

—The Editors

Teaching English as a Second Language

BY JAMES WACHOB

James Wachob was featured in the Wilson High School newspaper in Washington, D.C., during his 2004-2014 tutoring stint.

Courtesy of James Wachob

When I retired from the Foreign Service at age 60, I strongly wanted to “give back” some of the fruits of my exciting and challenging Foreign Service assignments. I was particularly interested in applying the skills in writing and in cross-cultural communication that I had honed in the course of a 37-year career that included seven overseas postings.

A Foreign Service spouse had once told me of the satisfaction she derived from organizing groups to learn English in countries where it isn’t widely spoken. Her enthusiasm for English as a Second Language instruction motivated me to consider employment as an ESL instructor in the Washington, D.C., area, where my wife and I reside in retirement.

A novice on ESL matters, I sent employment application letters with my résumé to four ESL schools advertising in the Yellow Pages. One of them was so enthusiastic about my qualifications that its management tracked me down in Los Angeles, where I was administering Foreign Service oral examinations during my final State Department assignment. They promised to hire me without an interview if I agreed to report to their Rosslyn branch on the first day of my retirement from State, a condition to which I readily agreed.

When I reported to the school, the receptionist handed me a book used to prepare students for the international Test of English as a Foreign Language. I hadn’t even heard of TOEFL or that publication, but she said, “You'll be in Room 4. Your students are waiting for you.”

My Foreign Service experience, which included instances of successfully facing situations far more alarming than this, gave me confidence for my debut. I was pleased to be named the branch’s senior instructor soon after that, and spent a total of 16 satisfying years in that line of work.

As my wife’s Parkinson’s disease worsened, I took a volunteer appointment to the ESL department of a public high school in the District of Columbia so I could spend more time with her and her nurses. My twice-weekly series of one-on-one sessions, again exclusively with foreign students, began as a continuation of my TOEFL program at the private schools. However, the main thrust of my high school sessions evolved into mentoring students who were underperforming for various reasons.

With the full support of the ESL department, I was successful in encouraging many students to alter the negative behavior that had led to their being referred for mentoring. After seeing substantial improvement in those students, some department teachers began sending me students “whom only Mr. Wachob can handle.”

After 10 years at the high school, I decided to end my volunteering on my 87th birthday. I look forward to seeing some of my former students again, either here or perhaps in their home countries. Now widowed, I find those reunions an immensely rewarding part of my life after the Foreign Service.

Retiring Overseas

BY SUE H. PATTERSON

Sue Patterson (second from right) interacts with WINGS youth peer educators two years into their activities.

Courtesy of Sue Patterson

There is life, adventure and deep satisfaction in retirement. Making one’s own life does require a steady income, initiative and the willingness to take a few risks, along with knowing yourself and what brings you satisfaction.

I chose to retire from the Foreign Service 19 years ago, after my final assignment as consul general in Florence. When I decided to make my home in Guatemala, where I had previously served as consul general for four years, my friends in Tuscany (and other places) thought I was in need of psychiatric treatment.

Some days I think they were right, but on the whole it was a good choice for me. Antigua—the colonial United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization site where I live—offers a fabulous climate, a lower cost of living than most places in the United States and plenty of stimulation. And it’s surrounded by beauty in both the landscape and the Mayan culture. It also has a plethora of thorny but compelling social issues, which is what, in fact, pushed me to come back to settle.

It was during my time as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Colombia, more than 40 years ago now, that I learned I have a deep passion for trying to help poor women get better control over their lives. The paths that opened for me here, which provide structure to my days and occupy a lot of volunteer time, are family planning (via www.wingsguate.org) and reducing chronic malnutrition (www.aldeaguatemala.org).

Guatemala has both the highest fertility rate in Latin America (half its children are younger than 5) and the fourth-highest rate of chronic malnutrition in the world. Obviously, there is plenty of work to be done in these two intersecting areas, as in many others. Gratification and opportunities abound.

To ensure that a choice similar to mine is going to work, it is necessary to be in a community with plenty of stimulating, like-minded people with whom one feels comfortable. For me, that is mainly a generous supply of fellow expatriates, not the rural Mayans I try to serve in my volunteer work. It also requires access to family and friends in the United States, as well as amenities like books, music, travel opportunities, a good climate, a university and a public library.

The decision to retire overseas takes time to ferment, and is enhanced by having previously lived in the potential destination. It is also true that only our excellent government benefits make such a choice possible for those of us having no other income streams. Serious volunteer work abroad or in the United States can be every bit as fulfilling as were our Foreign Service careers.

Working and Reporting on Environmental Issues

BY BOB TANSEY

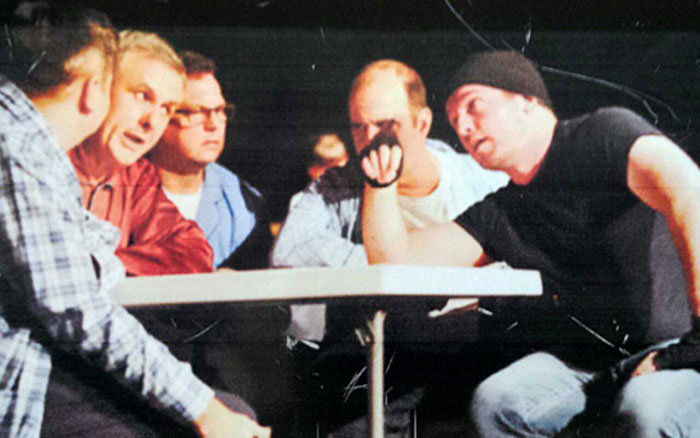

A pot-luck farewell reception for Bob Tansey, third from left, at his apartment in Beijing.

Courtesy of Bob Tansey

I retired on Sept. 30, 2009. Looking back, I feel like I was pretty well prepared. I think State’s four-day workshop is great. I also did the two-month transition and job search program just before I retired, and that provided lots of useful information and insights.

My advice—whether to my younger self or to colleagues preparing to retire in the foreseeable future—is to look for what you love and prepare to do it for the rest of your life. I’ve been a Buddhist all my adult life, and that gives me an orientation to service and to ongoing self-development. So I figured out early on that I wanted to keep working and contributing to society in retirement.

Naturally almost everyone thinks about the basics like financial viability in retirement. But I believe it is also hugely important to consider what will bring you joy and fulfillment. The Foreign Service is a very particular kind of career, so it’s important to step back and ponder, “What do I want to do for the rest of my life?”

Before I joined the Foreign Service in 1985, I’d only been to the Canadian side of Niagara Falls and to Japan. I spoke a bit of Spanish. Now I’ve lived in eight countries, visited 63 (and counting), and have been able to communicate with fascinating people in Spanish, Mandarin Chinese, Russian and Turkmen in addition to my native English. It’s probably good to have more experience with the world outside the U.S. than I had before joining the FS, but for me and my family it all worked out.

Because I had won the 2007 Frank E. Loy Award for Environmental Diplomacy for my work as an environment, science, technology and health officer in Tel Aviv—including my contributions to Israeli-Palestinian water cooperation—and because I’d also studied Mandarin in Taiwan, and then worked in Beijing and Chengdu, The Nature Conservancy hired me in early 2010. I started in Beijing but am now at TNC’s world office in Arlington, Virginia, supporting our China program from here and engaging with policy innovation teams across the organization’s major goal areas: land, water, oceans, sustainable cities and climate change.

To me, it’s some of the best work in the world. Serving in almost all regions of the world was probably too eclectic from a Foreign Service careerist standpoint, but that mix is really paying off for me now in my global role with TNC.

I tell friends still in the FS—including highly accomplished colleagues—to apply now for some things that by their nature involve long application and decision processes. That’s a safe way to start figuring out what your own future “dream job” might be—assuming you want to keep working. I still quote the great lines from counselors at the career transition course: “Go for the offers! You can turn down the offers you don’t want, but you can’t accept the offers you don’t have.”

Do What You Didn’t Have Time to Do

BY CRAIG OLSON

My response to your request to describe life after the Foreign Service has a twist. More than 80 percent of my working life occurred before I joined the Foreign Service.

You see, I entered the Foreign Service as a political officer at the age of 58. And no, I was not an appointee; I took and passed the exam after several tries. (I don’t know if it’s true, but I’ve been told I am the second-oldest person to have entered the Foreign Service in history.) I served in Colombia and Kenya, then spent the remaining two years of my FS career in the Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

My philosophy has always been that retirement is the stage in life when you do things you didn’t have time to do—or, for legal reasons, couldn’t do—while working. In my case, that has included political activism, travel, bridge, golf and spending lots of time with our six grandchildren.

Ink in My Veins

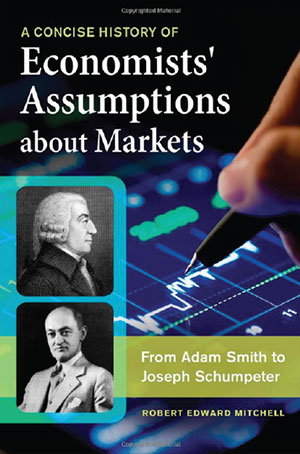

BY ROBERT E. MITCHELL

I was a mid-career transfer into the Foreign Service, a targeted recruit from academia with analytical skills needed at the time by the U.S. Agency for International Development. With USAID I was able to continue what I was already doing, but without the time-consuming challenges of preparing courses, teaching and encouraging students. I missed that, but found program management and development work very rewarding.

Heavy time demands placed on overseas USAID staff didn’t allow much opportunity to plan for what one would do after mandatory retirement at age 65. But I greatly benefited from the one-month retirement workshop the agency offers those about to retire. I sorted out my financial and other challenges while slowly slipping back into my earlier academic environment by taking advantage of the learning and research resources in the Washington, D.C., area.

Ink is in my veins, so writing (and publishing) compensates for my near-deafness, an affliction that makes social relations very difficult. I can live within myself, as I have had to discover.

I do miss the challenges of an overseas Foreign Service career and certainly benefited from multiple long-term postings in the Near East and Africa. But I was always a particular type of nonpolitical activist, a disease that began well before my rewarding career with USAID. That early history helped me forge a meaningful post-retirement life. I’m still plugging away at publishing and both taking and leading courses for fellow (non-Foreign Service) retirees.

Keeping the Mind Sharp in Retirement

BY DAVID SHINN

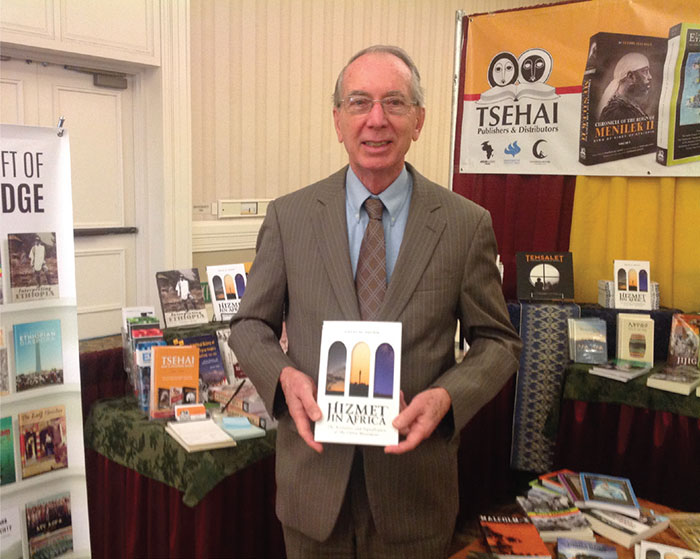

David Shinn with his book, Hizmet in Africa, at the African Studies Association Conference in San Diego in 2015.

Courtesy of David Shinn

A Foreign Service career comes to an end for most of us at a relatively young age, our late 50s or early 60s. Assuming good health, there is a great deal one can do during a long period of retirement.

That said, moving to a second career may be harder than you think, even when you seem to have all the right credentials. Armed with a Ph.D. and teaching experience at Southern University and the University of California at Los Angeles, thanks to the State Department’s diplomat-in-residence program, I thought advancing within academia would be relatively simple. But it soon became apparent that I had not punched the necessary tickets to assume a senior teaching position.

So instead, I began adjunct teaching in the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University. That may actually have been the better choice, it turns out. While the pay is modest, I control my own schedule and effectively have no bosses—a huge plus after 37 years in the Foreign Service. The moral here is to be realistic about second careers and prepared to accept something less than your first choice.

Everything considered, there is little I would change in my planning for life after the Foreign Service. Your spouse or partner needs to be part of the process and in agreement with your plans. You should have some idea where you want to live, and what you would like to do. Financial planning that leads to financial flexibility is also important.

I knew long ago that teaching was a possible second career, so I decided to get a Ph.D. while still in the Foreign Service. I wanted to remain engaged in international affairs. That argued for staying in the Washington area. We already owned a home on Capitol Hill, and it was easy to stay put. Frugality and careful investing while in government resulted in financial flexibility. Voilà! It worked out, just not at the level I had initially envisioned.

Before joining the Foreign Service, it never really occurred to me that retirement might last so long. The corollary is to stay physically fit. I did not begin a serious physical fitness program until age 60.

In addition to teaching, an activity that helps keep the mind sharp and the psyche young, I have co-authored two academic books and published a third on my own, all dealing in some way with Africa, which was my area of specialty in the Foreign Service. But I also needed to get up to speed on China for a major tome on Beijing’s relations with the continent, so I made multiple visits there. Another book dealing with the Gülen Movement in Africa reacquainted me with Turkey, a country I had not visited since 1966.

Besides contributing numerous articles to policy and academic journals, I’ve also given lectures all over the world and advise or serve on the boards of a half-dozen nongovernmental organizations. My bottom-line advice to prospective retirees is to remain physically active and mentally engaged to make the most of retirement.

Use Your Connections

BY JIM MEENAN

Jim Meenan (right), with his wife, Vera, advocates for the Foreign Service with Representative Gerry Connolly (D-Va.) at the congressman’s annual St. Patrick’s Day event.

Courtesy of Jim Meenan

All too often, Foreign Service personnel don’t think about planning for retirement when we begin our careers. As a result, retirement sneaks up on many of us.

What is it that you would really like to do now that you have a retirement annuity to help meet your daily needs? The earlier you can answer that question, the better positioned you will be to achieve your dreams, by ensuring the skills you are developing and the training you are receiving will furnish you with the qualifications you’ll need during retirement.

While in college, I had the pleasure of briefly meeting John F. Kennedy during his presidential campaign stop in Los Angeles. He proved most inspiring and sparked a desire to do more in my career than just hold down a job. I wanted a challenging international career where I could make the most use of my education. Shortly after graduation, The Wall Street Journal ran an ad announcing openings in my field of expertise in more than 87 countries with an organization called the U.S. Agency for International Development.

My first assignment after joining the Foreign Service in 1965 was Saigon, so I realized right away that my career would prove to be challenging, as well as rewarding. I served in a variety of hot spots, from Chile and Panama to Sri Lanka and the Philippines. What I learned throughout my career is the need to stay flexible and seek new ways to contribute to the U.S. objectives in each particular country or environment. Toward that end, I changed my career path from one pointing out areas for program improvement to actually designing the programs and managing their implementation. As a bonus, I figured that would give me employable skills later in my life.

I also observed, during my Vietnam assignment, the importance of staying in touch with one’s congressional representatives. One senior officer was promised his next assignment would allow his family to accompany him, and when that did not happen he contacted his representative, who happened to be Tip O’Neill Jr., the Speaker of the House. His situation was quickly corrected.

Although my Foreign Service career had focused heavily on private enterprise development, I was fortunate to have secured (under the Foreign Service Act) a three-year assignment as legislative assistant for trade and economic development to Senator Max Baucus (D-Mont.). This assignment helped pave the way for a post-Foreign Service career in international trade, with both private firms and trade associations. I also joined the U.S. Department of Commerce private sector trade advisory group for small and minority business, as well as its intellectual property sister committee.

I later received a call from the chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Small Business to join his staff as its senior trade adviser, which led to useful hearings about the shortcomings in U.S. trade promotion. (I continue to maintain some congressional contacts as I volunteer on the AFSA Political Action Committee Advisory Board.)

My concluding advice: As one proceeds through a Foreign Service career, one should stay alert to making the most of the skill sets that are being developed, with an eye to ensuring they will be of assistance during retirement.

Activism Through Volunteer Work

BY JACK R. BINNS

There is indeed life after the Foreign Service, and it can be very fulfilling. Moreover, it may continue for an extended period, as in my case. Of course, other persons’ trajectories may not be as favorable as mine, or as that of my friend and colleague, Ray Seitz. When he retired from the Service and became a Lehman Brothers director, Ray observed: “I can continue to wear all my pinstripe suits: no change of wardrobe required!”

My wife, Martha, and I returned to our home in Washington, D.C., from Madrid in early 1986, ready to start new lives while remaining in our comfort zone, near friends and colleagues. My original plan had been to do consulting work and start a Spanish antiques business on the side. To that end, I had established a relationship with a Madrid dealer and brought back a container-load of goods at my expense. But within two months I discovered my profit margins would be small, and the work would take a lot more time and effort than I was prepared to expend. Antiques were just not my bag!

Consulting work offered a more rewarding way to make a living. Among other gigs, at the behest of the Diplomatic Security Bureau I headed a small team that designed and conducted emergency planning exercises at embassies and larger consular posts. For nearly five years, my team visited and conducted exercises throughout Latin America and Europe—as well as Syria, for reasons I no longer recall.

For her part, my wife became a travel agent, then moved on to the National Planning Association—a nonpartisan think-tank that brings together business, labor and academia—as a meeting planner. We both were having a great time, but eventually got itchy feet. The Southwest beckoned! After much research, we moved to Tucson, Arizona, in October 1990.

We found a beautiful house and settled in. In addition to lots of golfing, we both joined the boards of all sorts of local groups: the League of Women Voters, a local country club, an FS retirees group (which ultimately folded), the United Nations Association of Southern Arizona, the Tucson Committee on Foreign Relations and the Latin America Center at the University of Arizona.

Eventually I became the public affairs director for the local Planned Parenthood chapter, and that proved to be a turning point in our lives. The best part was the chance to form strong ties with a younger group of like-minded friends. They are very tolerant of the aged!

We also keep in touch with our FS friends, some of whom are winter visitors, and we see others when we go east to visit our New York-based daughter. Our other daughter lives in Australia with our only grandchild, but our parents faced the same long-distance challenge with us.

So, yes, kind readers, there is definitely a life after the FS. And there’s also a hitherto absent sense of permanence. As best Martha and I can recall, we had 23 full household moves, sometimes two or three in the same city, during our 35 years in the Navy and Foreign Service. Since retiring we have moved three times, and have been in our current residence for 23 years. The thought of yet another move is appalling, but no doubt inevitable.

Two More Careers Open New Worlds

BY GEORGE LAMBRAKIS

George Lambrakis (front, second from left) with his wife, Claude (front, right), at a dinner with the Brown University Club of South Korea in Seoul while on a fundraising trip.

Courtesy of George Lambrakis

At age 54, after 31 years in the Foreign Service (two with the U.S. Information Agency and 29 at State), I embarked on the second of my three careers: international fundraising. That was eventually followed by university teaching and administration in London and Paris.

I quickly learned the value of putting together an effective résumé, a task I had never had to perform during my time in the Service. On a happier note, I discovered that there are a lot of Foreign Service alumni out there who are eager to help you find a job, particularly in think-tanks and academia. Nor do you need to be a superstar or have the title of ambassador (which several universities unilaterally bestowed on me anyway) for such positions.

Following up on a tip from a retired FSO I didn’t previously know, and with the recommendation of former ambassador and Fletcher School Dean Ed Gullion, I was selected to establish a pioneer American university fundraising effort abroad at Brown University (not my alma mater). They preferred someone who knew his way around the world rather than any of the 250 other applicants with domestic fundraising experience.

Accompanied by my wife (at my own expense), I traveled to many countries we had never seen in the Foreign Service; got local country reports from savvy business people with whom, as a former political officer, I had had little previous contact; stayed in top hotels familiar to the wealthy prospective donors; and ate at top restaurants and was invited to stay in lovely homes. (My FS pension helped me make ends meet, given the lower starting salary at Brown.)

After more than three successful years at Brown, an old Foreign Service friend introduced me to the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, where I established a similar program. I then set up fundraising for the new Princess Royal Trust for Carers (which involved visits to Buckingham Palace, lunches with Princess Anne, and a broken ankle while out shooting near Loch Lomond in Scotland).

Next came a position as secretary general of the International Federation of Multiple Sclerosis Societies, where in the process of multiplying their fundraising take I got an education on brutal politicking between national chapters and prima donna volunteers in America and Europe. And finally, as the sole fundraiser for Passports for Pets, I helped inspire the campaign that succeeded in ending the draconian six-month quarantine of dogs and cats imported into the United Kingdom. In the process, I met more top society donors than I ever knew existed and earned the gratitude of people such as Governor Chris Patten, who was returning from Hong Kong with his two dogs.

My subsequent switch into academia was less dramatic. Foreign Service experience and a Ph.D. (from The George Washington University) won me the position of program head for international relations and diplomacy at the London branch of Schiller International University in 1994. I held that position until 2011, when I retired at age 80, having simultaneously taught courses at four other universities in London and directed the new American Graduate School of International Relations and Diplomacy in Paris.

So, my fellow FSOs, take heart. Your talents are highly marketable, and there is much to learn and enjoy once you realize that retirement, like college graduation, can open up new worlds for your delectation.

Breaking into Publishing

BY BRUCE K. BYERS

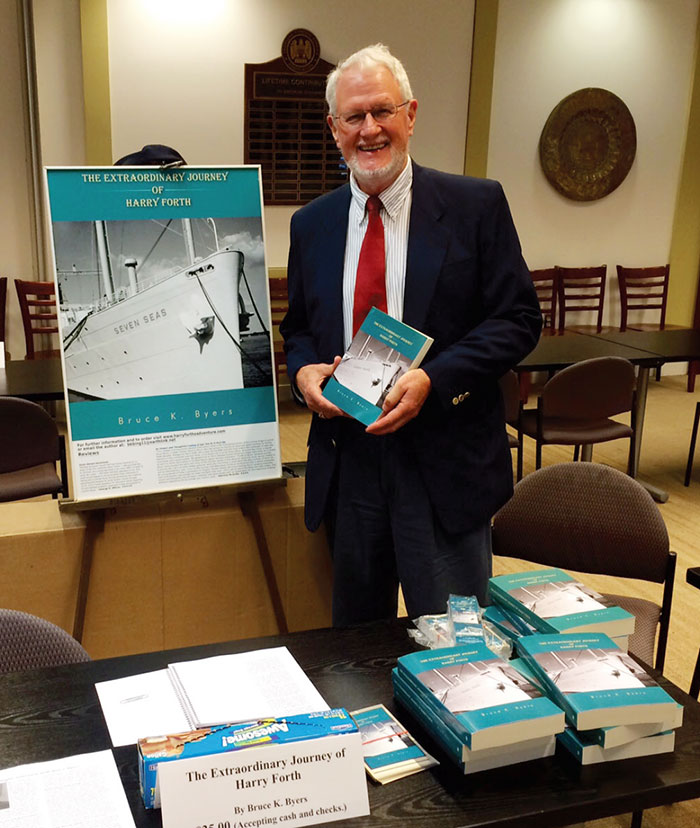

Bruce Byers with his book, The Extraordinary Journey of Harry Forth, at AFSA’s 2015 Book Market.

Courtesy of Bruce Byers

What do I wish I’d known before joining the Foreign Service? I would have liked to know more about the dislocation that moving overseas can visit upon a young family.

I grew up in a military family and was used to moving a lot. But there is a major difference between military life and Foreign Service life. Support for the families of armed forces members is much more developed, although there have been significant improvements in family support at Foreign Service posts.

How should a prospective retiree prepare for post-Foreign Service work (paid or volunteer) and other activities? Research your post-career interests as much as possible before you retire, and expand professional contacts in those fields while you are still employed. To the extent feasible, attend conferences, seminars and lectures in the areas you are interested in pursuing. And don’t neglect to join professional organizations that can help after retirement (AFSA and DACOR are two I have joined). Finally, hone your public speaking skills and expand the range of topics about which you can speak.

If you enjoy writing, start documenting your experiences while still on active duty. Keep photos, letters, articles and other memorabilia that can help in pursuing a writing career. (Remember, your children will one day want to know more about the early years in the Foreign Service when they were young and moving about the world.) Participate in writing workshops and seminars to establish contact with local authors.

While I worked as a WAE (now REA, or re-employed annuitant) in the State Department between 2001 and 2009, I published several essays on foreign affairs topics on different websites. I also wrote short stories related to my career experiences and my life before the Foreign Service, which were the basis for an autobiographical novel about my first trip to Europe as a high school exchange student.

Write what you would enjoy reading without worrying about publishing it. That way, the experience is more fun and less prone to disappointment. When you think you have something worth publishing, ask friends about their experiences and research the self-publishing industry thoroughly. Read contracts carefully and don’t assume anything.

What advice would I give my younger self about planning for life after the Foreign Service? First, I would emphasize the need to save throughout one’s career and avoid carrying major debt into retirement. It’s also advisable to maintain good relations with local physicians, dentists and lawyers.

I would establish a revocable family trust (much sooner than I did) as a means of protecting personal and financial assets. The trust documents include medical directives, wills and powers of attorney to protect us and our assets in case of certain life events. Shop around for a law firm that specializes in trusts, ask lots of questions during the initial interview with a lawyer, and take nothing for granted.

I would urge anyone on the verge of retirement to update their security clearance and maintain good relations with the bureau in which they are working at the time of retirement to be able to be considered for WAE positions. A current security clearance is very valuable if you contemplate working for any government contractor or other government agency. It opens many doors to post-retirement jobs.

A Satisfying Second Act

BY RON FLACK

Ron Flack.

Courtesy of Ron Flack

I retired from the Foreign Service almost 20 years ago, and still occupy the position I found in 1997. After I had completed the retirement course and the job search program, Taylor Companies, a private, family-owned investment bank in Washington, D.C., hired me to develop and manage a global network of senior advisers.

When I started, I felt like a junior officer in an embassy again. I had to learn how to function in a very different work environment, acquire computer skills and integrate my international experience into the company.

I am not an investment banker, but hire and work with our advisers, mainly retired chief executive officers whom I have recruited. They are key to the success of the company.

Soon after starting my work with Taylor, my wife, Daniele, and I moved to Paris, where I still represent them as co-chairman for Europe. Happily, at age 82 I can pretty much set my own work schedule. When I retired at age 65 I thought I would work perhaps another five years at the most! I am delighted to be still working, albeit less, and keeping active.

Allow me to offer a few recommendations to my active-duty Foreign Service colleagues.

First, throughout your career, develop and cultivate long-lasting relationships with contacts around the world. I still draw on my diplomatic experience and international contacts almost daily in my work. I think that it is easier for FSOs who have spent most of their careers abroad, rather than in Washington, to find satisfying international work in retirement.

Second, spouses can play a very helpful role in a second career. Daniele has kept in touch with foreign contacts even more regularly than I have. FSOs whose spouses accompany them abroad have a major advantage in seeking international work after retirement.

In the Foreign Service spouses are, as my fellow Minnesotan Hubert Humphrey once said, unpaid diplomats. The government gets two for the price of one. In retirement, as well, my wife of 55 years has been an integral part of the teamwork at the company, this time as a paid consultant.

I have often counseled young people who are seeking careers in the Foreign Service to consider the downsides of working abroad, such as raising a family in difficult environments and health issues, in particular—but also education and spouses’ careers. But raising a family abroad can also offer enormous advantages. In our case, we chose the French educational system abroad, and our children have their French Baccalaureate degrees—one from Athens, another from Geneva. They are totally bilingual and bicultural, and they often thank us for giving them an international upbringing.

A Foreign Service career is an exceptional and very gratifying way to spend the first part of your life. But a satisfying second career is equally important.

Enjoying Travel and Hobbies

BY JAMES PROSSER

James Prosser.

Courtesy of James Prosser

After 41 years in the Foreign Service, I retired to Green Bay, Wisconsin, where I was born. This is my 25th year as a retiree.

Pursuing my numerous hobbies (photography, trains, classical music, animals and wildlife, computers, telecommunications, amateur radio, gardening, swimming) never left time to engage in remunerative post-retirement work. But it has also meant that I never have to wonder what I’ll do each day.

One very enjoyable aspect of retirement after the Foreign Service has been the many opportunities to address schools, social clubs and other local organizations about the Foreign Service. This activity led me to mentor three college students on how to successfully pursue careers in the Foreign Service.

My wife and I lived in 11 different countries during my Foreign Service career, and we still travel the globe, making scores of close friends. Many of our voyages have been by sea on freighters, each carrying fewer than 13 passengers. We traveled all the way around the world on a Danish freighter!

People often ask us, “What was your favorite place or trip?” We usually respond that it’s impossible to pick only one. As long as our health holds out, we just keep on going.

Oh, and closer to home, we also have Green Bay Packer season tickets!

Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice

BY WILLEM H. BRAKEL

There are many onward paths following a career in the State Department. Over the past five years, mine has centered on teaching part time at the university level. I have found this to be extremely rewarding in various ways: the interactions with bright and curious students, the possibilities for sharpening one’s own analytic and presentation skills, and the opportunity to find some perspective and coherence (if only retrospectively) in the random moving around from issue to issue and post to post that is typical of a Foreign Service career.

As active-duty diplomats, we flit from one assignment to the next, focusing so much on the crisis of the day and the deadline of the moment that we have precious little time for reflection or strategic thinking. Academia offers an antidote to these tendencies. They say you never really understand a subject until you have had to teach it. And, as Socrates said, an unexamined life is not worth living. I feel very fortunate to have the opportunity for that reflection and self-examination today.

For those contemplating going in an academic direction, I call attention to the excellent, thought-provoking series of articles on the divide between scholars and practitioners of diplomacy in the January-February 2015 Foreign Service Journal. My only quibble, as a former economic-coned officer and scientist with 24 years in the Foreign Service, relates to that series’ relatively narrow focus on (geo)political issues.

Not long ago, I had the opportunity to teach a course on international environmental politics at American University’s School of International Service. In preparation I delved for the first time into the extensive scholarly literature on international relations as it relates to environmental concerns. (My own previous degrees were in biology.) Like several authors in the above-mentioned FSJ, I found that some academic writing was pretentious and pompous, and theoretical to the point of abstruseness. Yet I also found much that was useful and insightful and valuable—stuff I wish I had known better while I was still in the trenches drafting position papers, sharpening decision memoranda and delivering demarches.

Take, for instance, the academic literature on international environmental governance, which looks at the totality of institutions and arrangements and all their moving and non-moving parts. Over the years as an FSO I had picked up a lot of this in a piecemeal fashion. Yet if I could have given some advice to my younger self, I would tell that slimmer, hairier Willem to seek out opportunities for reflection and learning about his profession outside of the day-to-day grind of work. He will need that broader perspective in more senior positions later on and in retirement—and it will make him a better officer in the near term.

And I would also tell him to not be shy to bid on assignments that interest him and allow him to develop new skills and experience, even if they do not appear to be promotion-worthy or career-enhancing in the immediate term. In my case, several assignments that might appear off the beaten path (a teaching stint at FSI; an out-of-cone assignment that involved lots of negotiation; a detail to an international agency involving lots of practical, hands-on experience) helped me immeasurably in the Senior Foreign Service and paved the way for a rewarding career in semi-retirement.

Making the Best of Premature Retirement

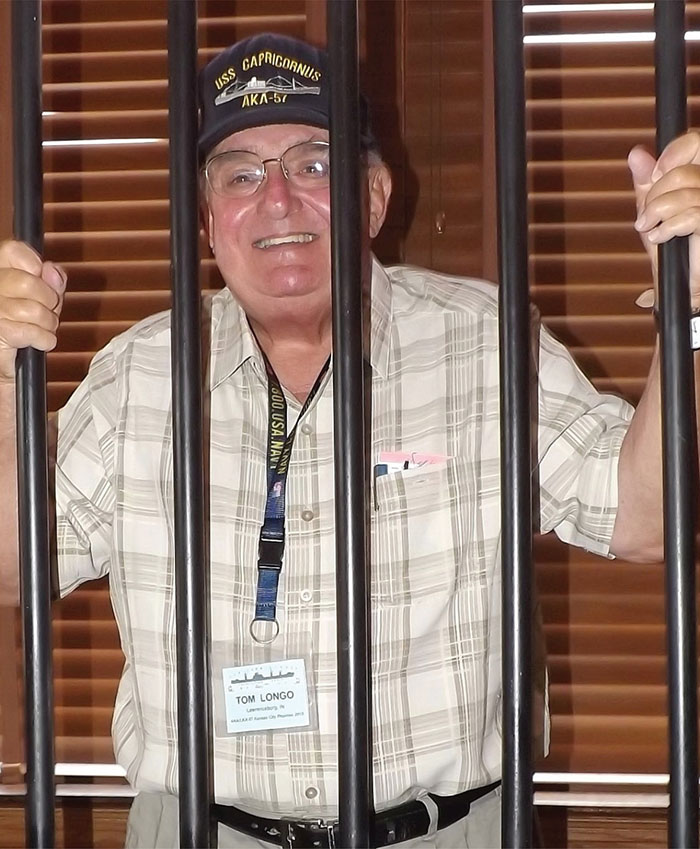

BY D. THOMAS LONGO JR.

D.T. Longo Jr. “in jail” at the USS Capricornus Association’s 2015 reunion in Kansas City, Mo. Longo has headed the naval ship association since 1999. The “cell” was a mockup in the restored Leavenworth, Kansas, train station, which is home to large U.S. military and federal civilian penitentiaries.

Courtesy of D. Thomas Longo Jr.

It’s one thing to retire after a full career in the Foreign Service. It’s quite another to be retired prematurely, and involuntarily, for reasons unrelated to job performance.

That’s what happened to me in 1993, when my time in class expired before I could be promoted into the Senior Foreign Service. The demise of my career resulted from shifting multifunctionality standards for promotion, as well as budgetary constraints and legal limits on the State Department’s ability to confer promotions.

To be booted out that way was a searing experience, since I had planned to continue devoting my life to the Foreign Service. It was a psychological stunner that contributed, in part, to my divorce two years later. It also dissuaded me from ever again wanting to be hostage to an employer’s whims.

Fortunately, I qualified for an immediate earned annuity, for which I am eternally grateful. Thanks to cost-of-living adjustments and careful budgeting, I lead an agreeable existence.

I continue to engage in various volunteer activities, such as serving on the board of a regional symphony orchestra, heading an alumni association of former U.S. Navy crew members since 1999 and participating in AFSA’s Speakers Bureau. I am also president of eNARFE, the virtual electronic chapter (with more than 30,000 members) of the National Active and Retired Federal Employees Association.

For me, these pursuits are a way to give back to fellow veterans and my country, from someone grateful to have served his country, to receive a decent federal annuity and, at age 73, to enjoy pretty good health.

I wish I had known before entering the Foreign Service that despite whatever dedication you bring to the “needs of the Service” and whatever accomplishments you achieve, it’s not enough to think, as I perhaps naively did, that doing a good job will bring its own reward. Promotions are in good measure a matter of luck and whom you’ve met along the way to mentor you and give you a boost. The pernicious up-or-out system obliges the Service to cast out perfectly good people. What a waste for the country to squander experienced, good FSOs.

Speaking to various groups ranging from high schoolers to senior citizens, I do encourage others most sincerely from my own experience that the Foreign Service is extremely interesting, important and worthwhile work. You will be challenged, you will not be bored, and you will have fun. But keep your eyes open about what you’re getting into: a full career and promotion to senior ranks are susceptible to ever-varying considerations beyond the fact that you stood up, saluted, went where the Service sent you and consistently did a great job.

Random Tandem Thoughts on FS Retirement

BY DAVID T. JONES AND TERESA C. JONES

David and Teresa Jones.

Courtesy of David T. Jones

When we entered the Foreign Service (David in 1968 and Teresa in 1974), the institution was on the cusp between the “old” and the “new” (and still evolving). Diplomacy was a profession, lasting a working lifetime—not a job. Although there was selection out and time-in-class restrictions, the system gently managed successful diplomats at the upper mid-level and senior ranks. They could expect to retire at their leisure in their 60s, and gold-plated, escalator-claused annuities permitted them to live comfortably without a second job.

The new Foreign Service, which we had to navigate and which all current FSO must master, is more demanding. The first lesson for newly minted diplomats is to understand the federal bureaucracy thoroughly to better enhance their careers.

Here are some additional observations for active-duty FSOs that will help ensure you can look back on a satisfying career:

Find a mentor. Locate an upward striving, congenial superior in an area that interests you. Be prepared to go to the deepest-darkest (as well as lightest-brightest) with him or her. Work like hell to be an indispensable team member (in 30 years of active duty, I logged seven years of uncompensated overtime and regretted barely a minute of it). But at the same time, start building your own team, those you want to lead when opportunity permits.

Leave previous experience behind. Your former academic, professional study or work will likely be irrelevant. A decade of East Asia study never resulted in a Far East assignment for one spouse; native Mandarin was never used professionally by the other.

Tandem status helps. The end of prohibition for married women as FSOs in the 1970s created “tandems”—with minuses as well as pluses. Now we must address the bitter spouses who couldn’t pass the FS entry exam. But “tandem” status is financially invaluable, especially in retirement.

Keep your original spouse. Divorce is expensive; multiple divorces even more so, especially when significant percentages of your pension goes to the spouse.

Preparing for retirement:

Assess your circumstances. Consider a final assignment to make you a Spanish-speaker if you do not already have that language. Obtain “While Actually Employed” (now REA) status. It is easier to arrange before retirement and opens paths for short-term assignments as an inspector, “gap” replacement or regular State work (e.g., Freedom of Information Act declassification).

Review your physical health. Do you need to diet? Do you have an exercise regime?

After retirement:

Do nothing dramatic for a year. Don’t plunge into a new job or a volunteer commitment (those are easier to get into than out of). Remember: Volunteers are welcome, but not honored. You get real respect by being paid.

Don’t sell your house and move “home.” You may quickly find that Centerville, USA, is Dullsville, with beloved relatives in cemeteries and “old school friends” passé. Moreover, it takes at least a year to move, reorganize and create new “trap lines.” Do you really have a year to spare for that?

Expand your social circle. This may seem obvious, but it is important to find younger friends (less likely to die on you).

Most important of all, enjoy every day! You have fewer ahead than behind.

Picking Up Again in Academia

BY AL KEALI’I CHOCK

On my retirement from the Foreign Service, my wife and I moved to a nonprofit retirement community, Pohai Nani, which is a month-to-month rental in Hawaii with a $250,000 entrance fee. We enjoy regular meals, many social activities, as well as bus service to shopping areas, theaters and concerts.

Fortunately, I had previously taught ethnobotany at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa as a lecturer, a paid position. After retiring, I was appointed to the adjunct faculty (unpaid). And after a decade and a half, I got an office (which I share with a post-doctoral student) that contains my technical and Hawaiian library—the equivalent of three wall-to-floor bookcases.

Warning: Once the word gets out that you’re retired, you will have numerous groups recruiting you. My first decade was filled with voluntary community boards and organizations (as many as six!), including two years as president of a master community association.

Be prepared: As a senior, you will soon find that there are numerous body parts that will fail, and you need to be close to major medical facilities. Forget that dream of living in a forest or rural setting! Since my retirement in 1992, I have had two complete knee replacements, as well as back (laminectomy) and right shoulder (rotator cuff) surgeries.

I wish I had today’s annuity, with locality pay, and double what I had in 1992!

Expect the Unexpected

BY DIANA PAGE

Diana Page with her husband in the Andes mountain range in the Atacama region of Chile.

Courtesy of Diana Page

Despite preparing for mandatory retirement at 65 (which should be raised at least high enough to match the age to collect full Social Security benefits), the first few years of what I prefer to call “reinvention” were full of discoveries and disappointments for me.

I say this even though I approached the process as if I were going back to college: a freshman year for experimenting, then the traditional overconfident sophomore year. That would perhaps be followed by a junior year abroad or other challenges, after which I hoped to use a senior year to focus on what lies beyond that.

My husband and I expected to have our own little vineyard in Chile; instead, we ended up as tenants on an avocado farm. (“Yes, I know you thought you’d try a cabernet sauvignon, but how do you like this guacamole?”) Hidden in a valley an hour from Santiago, the farmhouse is not glamorous, but the rent is quite economical. It also allows us to escape winter in Maine from November to April.

I also expected my good health to last a long time—until the day pain developed in my knee, eventually forcing the choice between giving up walking or surgery. I chose knee replacement, but that changed my “junior year” into one of not going abroad. And despite planning many sentimental journeys, I found out that family issues—such as becoming grandparents—will defer your travel. My advice to fellow retirees: travel sooner rather than later, because you never know what’s coming.

My four years of reinvention did not bring what I expected, but they brought some advantages that I never anticipated: the fun of learning how to cook whatever is in season, the pleasure of a good library that is also a community center, and the satisfaction of being an opinionated citizen in a lively local democracy. (I’m working with Maine Moms for Gun Sense on a referendum to close loopholes on background checks.) When traveling, I find freedom to engage in discussions at all levels as just an American, not as a diplomat.

My advice to those planning to live abroad is try it for a year or so before shipping your household goods. You may miss all the acronyms, such as FSN, GSO, APO. You will inevitably spend days in lines in ministry corridors. (My husband is Chilean, but I cannot get permanent residency due to our dividing the year between the United States and Chile.) Foreigners also have trouble getting bank accounts; it seems we’ve been too successful in blocking money laundering. On the bright side, the greatest boost to travel since no-frills airlines is the online home-away-from-home website, Airbnb. I love it!

Launching a Documentary Film Company

BY LEONARD HILL

Leonard Hill and his wife, Cathy Stevulak, interview Bangladeshi artist Suraiya Rahman in Dhaka for the documentary film “Threads,” which recently completed its film festival run.

Anil Advani and Kantha Productions LLC

My post-retirement path has been partly traditional—rediscovering the ups and downs of living in my own house, several months of WAE (now REA) work a year—and partly unconventional. Launching, with my wife, a documentary film production company a year into “retirement” was definitely not one of the things we had talked about or planned during the Job Search Program.

Here are a few things that I’ve taken away from the process:

• An “extended home leave” cleared the decks for the next phase of life. Approaching retirement as I would home leave—a time of transition to something new, with a lot of things to do to get ready—worked well for me and my wife. I focused on getting through a list of necessary but not necessarily exciting tasks—e.g., renovations to our house, figuring out what to do with stuff that was in storage—rather than thinking too much about my new status (or lack thereof).

Before I knew it, I had both accomplished the tasks on the list and found myself headed on a completely unanticipated path.

• Be open to a change. Although my wife and I want to be near our aging parents, who require some assistance, we have tried to keep ourselves as flexible as possible to take advantage of new opportunities.

• Networks matter. From WAE assignments to finding a film crew in Bangladesh, people I met during my diplomatic career have been crucial to what I have done since leaving the Service. Staying in touch or reconnecting with friends and colleagues has been one of the pleasures my wife and I have enjoyed post-retirement. And the networks that we developed have helped us immensely, either directly or by introducing us to others who have been helpful.

Making an independent film—as anyone who stays in the theater to read the credits knows—takes a lot of people; introductions and recommendations make finding them so much more effective.

A Retirement Adventure

BY JUAN BECERRA

Juan Becerra (third from left) at an Information Resources Management award ceremony at Embassy Brazzaville in 2015.

Courtesy of Juan Becerra

The thought of retiring was frightening, but I can attest that there is life afterward. You do have to make adjustments to survive financially, however. I wish that I had known the value of formulating a “What do I really want to do?” plan before retirement. Financial stability and a home are important, but so is keeping yourself occupied after you retire.

As a Vietnam veteran, I decided that I would help my fellow vets by volunteering at the local Veterans Affairs hospital. That turned out to be rewarding as well as challenging, because I didn’t always understand the patients I worked with.

I had been lucky enough to return from Vietnam with minimal problems, but many of my peers had not been so fortunate. The same was true of many veterans of other wars and conflicts. Despite my best efforts, I could not relate to them.

So after a year of volunteering at the hospital, I decided to start traveling to visit family and friends and visit places I had always wanted to see. I did that for several years until one day, when I received an email from a Foreign Service colleague asking me if I might be interested in doing “While Actually Employed” (now “re-employed annuitant,” or REA) work. I jumped at the chance and here I am today, heading off to an assignment in South Africa next.

I would advise anyone interested in volunteering to try it out for a while and see if it’s really what you want to do. I found that I missed the travel, the adventure, the challenge of FS work and my Foreign Service colleagues. I have given myself an “end date” of 2017, and still plan to “completely” retire next year.

I am happy and ready for the next adventure in my life.

Happy to Be Alive

BY ALAN L. ROECKS

When I retired from the State Department Foreign Service in 2012, I was in good health. But a year later, in October 2013, cancer struck. Over the next two years, after 21 painful immunotherapy treatments and numerous hospitalizations, I would lose a kidney and bladder, and now wear an external pouch. I was depressed and wondered if I would make it to age 70.

Fortunately, I had a spiritual companion. When times were difficult or I had considerable pain, I would close my eyes and Mother Teresa magically appeared to comfort me. My wife, Jane, and I had happened to have a private, 45-minute meeting in her Kolkata office years before. Mother Teresa thought I was there for visas, but I had brought used computers, which it turned out she could not use.

Though I had planned to write in retirement, it didn’t happen—the medical challenges created writer’s block. (This is my first writing since retirement.) Channeling frustrations of self-pity into something positive, I set up an American Foreign Service Association retirement group in Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho, established a nonprofit foundation and a bladder cancer support group.

The overseas group was a wonderful stress-reliever and provided a collegial forum to discuss international politics and happenings in the Foreign Service, and reminisce about past postings. We talked, for example, about the Foreign Service Institute’s Job Search Program, an option most of the group had not pursued when retiring.

As it happens, the Job Search Program had prepared me well. Room and board costs were offset by remaining longer on the payroll. Upon completion, I knew what I wanted to do with my Thrift Savings Plan and Social Security, had prepared a 10-year financial plan, and decided to set up a nonprofit foundation and keep my federal health insurance (a move that has saved me thousands of dollars in medical costs).

Setting up the nonprofit foundation was tricky and time-consuming, but represented a welcome diversion from ongoing cancer treatments and surgeries. The foundation embraces international medical, educational and humanitarian causes. In Addis Ababa, my last posting, our family became involved with a youth tennis academy and decided to sponsor a student to study in the United States.

Because Ethiopia is not exactly known for its tennis players, it was a hard sell. But we finally found a college in Lewiston, Idaho, that offers an excellent tennis program for international students. Yonas, the student we’re sponsoring, joins our family during holidays and school breaks, and we follow his tennis team. The foundation also sponsors a humanitarian award for a student from my high school and helps support Missionaries of Charity in Bhagalpur, India, the birthplace of our two adopted children.

Looking back, I wish I had known about the Foreign Service out of college. I joined State as a specialist at age 42, later moving to the FSO management track. Overseas international schools provided a comprehensive college-preparatory education for our children and a stimulating professional environment for Jane, an elementary teacher.

My close medical calls since retirement have made me appreciate life, particularly my overseas experiences with the Foreign Service, more than ever. I am grateful for my pension; excellent, affordable health insurance; and the flexibility to engage in the activities of my choice.

Fulfillment in the Nonprofit World

BY LAMBERT “NICK” HEYNIGER

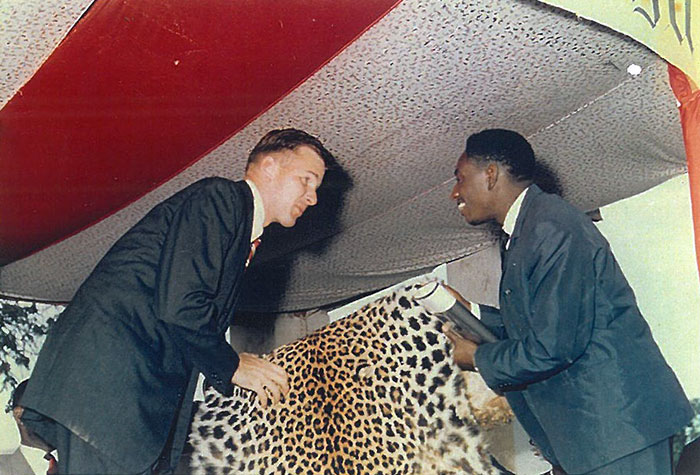

Nick Heyniger (left) in Katanga Province, Southeastern Congo, in 1965 at the investiture of a new tribal chief up-country. Heyniger gave the chief a set of USIA books, and the chief gave Nick a leopard skin.

Courtesy of Nick Heyniger

I joined the Foreign Service in 1956 and served first as a consular officer in Amman and, thereafter, as a political officer in a series of overseas postings and assignments in Washington, D.C. These included the Bureau of Intelligence and Research and the Office for Combating Terrorism, among others.

After retiring, I moved with my Foreign Service wife to Montreal, Canada, and found a very pleasant and fulfilling life as an executive at a family foundation.

Before joining the Foreign Service, I wish I had gone to the Georgetown School of Foreign Service. As a political officer I never was given any training whatever on how to perform in that position.

Before retiring, I wish I had known more about the not-for-profit world. As it happened, I found my next job in Montreal, working for a family foundation, but that was more a matter of luck than design.

Theology and the FS

BY FR. THEODORE LEWIS

The Reverend Theodore L. Lewis.

Courtesy of Theodore Lewis

Life after the Foreign Service may be daunting to contemplate, at least for those not content with golf and cruises. The skills we develop in our careers, the disciplines we acquire, arise outside the usual American context. We may wonder how they can be relevant in that context. Further, in our assignments we deal with vital matters both national and international. Postretirement, such activities as community service, consulting or teaching may be available to us. But can they give us anything like the same sense of purpose? I do not have final answers to these questions. But I can tell how in my own case they were answered positively.

My retirement came about abruptly; I had little chance for advance planning. But I had been to seminary along the way, and I had already conceived an idea for a book. This was to discern a particular theme in biblical redemption history, the story running from Moses and the Exodus through the death and resurrection of Jesus (“power lies ultimately in acceptance of our powerlessness”). It would then trace application of this theme to subsequent history—history of the world, as well as the church. And my toolkit for the discernment and the tracing would be my Foreign Service disciplines.

My retirement gave me time to work on the book. But I lacked the supervision as well as access to needed research materials. To find them I went to England and took up residence in an Oxford theological college. One of the tutors there was pre-eminently qualified to supervise me; subsequently, he became one of the world’s best known theologians. But I lacked academic credentials; would he take me on? He did, solely on the basis of my Foreign Service disciplines!

I did not finish the book while in Oxford, but I acquired sufficient momentum to carry it to completion later. That enabled not only continuing contact with my Oxford mentor but also acquisition of an American one, similarly world-famous. At the latter’s urging, I wrote Theology and the Disciplines of the Foreign Service. It was reviewed in the April 2015 issue of The Foreign Service Journal, and its United Kingdom launch in Oxford the following October was well received.

My experience shows that Foreign Service disciplines are, in fact, applicable beyond its ranks, at least where theology is concerned. But what about the sense of purpose that the Foreign Service conveys? Can this, too, be found elsewhere? With regard to theology, I would answer as follows. Its issues may not have the immediacy of those in the Foreign Service. They are not quite like crises in a particular country to be dealt with or urgent queries from Washington to be responded to. But I have found the issues themselves, involving as they do final questions, to be no less serious. In fact, their resolution may be regarded as bearing on eternal life and death. Accordingly, theology, instead of diminishing my sense of purpose, has enhanced it.

That my experience can be replicated in fields other than theology I cannot be sure. But it certainly seems possible. My only caveat would be the need to develop an interest in such a field prior to retirement. This could serve not only as a preparation, but also as a balance for the exigencies of one’s Foreign Service career.

Getting Involved in the Community

BY GEORGE G.B. GRIFFIN

As chairman of the PenMar Development Corp., George Griffin (right) receives a plaque from Fire Chief Dale Fishack in thanks for the fire truck the company donated to the Smithsburgh, Maryland, Fire Department.

Courtesy of George G.B. Griffin

On retirement, we decided to move to rural Pennsylvania. As we settled in, I began going to community meetings to meet our new neighbors.

At one of those meetings I learned that there was a movement to form an organization to ensure that local concerns were brought to the attention of authorities in our two-state, fourcounty area. (At the same time, I checked out a nearby foreign affairs study group. But, concluding that it was too simplistic and politically motivated, I didn’t join.)

The local group grew into a strong community organization, influencing county and state government actions. When I was elected its vice president, the president asked me to apply for membership on the board of a nearby Base Closure and Realignment Commission-mandated parastatal, which our members considered too secretive and unsuccessful in redeveloping an important former U.S. Army base.

Soon after joining that board, I was elected chairman; three years later, I won a second four-year term. By the end of my tenure, I had successfully negotiated the sale of the entire 600-acre property, and got the developer to agree to join in paying $6 million to build a new community center, which I helped design.

I later served as president of the community center, and convinced the board to donate a million dollars to the local primary school, keeping it open as an inducement to potential job seekers at the former Army base. I also became a trustee of an African wildlife conservation nonprofit organization, and was soon its primary fundraiser in the United States.

There is more than enough to keep one busy in retirement!

My Retirement Bucket List

BY GENE SCHMIEL

Gene Schmiel, in red, talks to fellow inmates of the asylum in a scene from the Fauquier Community Theater’s production of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

Courtesy of Gene Schmiel

During the retirement seminar, I made a list of desirable activities that I thought were “doable.” I’ve crossed many of them off my bucket list:

1. Acting: I’ve been in several community theater plays, including “Twelve Angry Men” and “Judgment at Nuremberg,” and have also directed productions.

2. Writing and speaking: I completed Citizen-General: Jacob Dolson Cox and the Civil War Era, a biography of the Civil War figure that was published by Ohio University Press in 2014. Since then, I have spoken to several Civil War groups around the country about the book and related topics.

3. Sports: I joined the golf club and made a “bucket list” golf trip with my son to St. Andrews in Scotland and the British Open.

4. Travel: My wife, Kathryn, and I take at least one major trip a year, most recently to Tuscany and the Baltic nations.

5. Work: In addition to being a WAE in the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs for 12 years, I taught foreign policy at a college internship program in Washington, D.C., for 10 years.

6. AFSA: I have worked with the AFSA-PAC team and as a judge for the High School Essay Contest.

7. Family: Most important of all, retirement allows us time to spend with our family, including our five grandsons, all living nearby.

Going “NOVA!”

BY ROBERT ALLEN POWERS

Not having a new assignment to look forward to can make retirement unsettling for some FSOs. But whether they appear by serendipity, as in my case, or from diligent searching, opportunities abound. My advice would be to think about what you’d like to do well before your retirement is at hand.

After 25 years in the Foreign Service, I retired on Jan. 4, 1995. Although I was anticipating a more tranquil lifestyle, retirement turned out to be far busier than I’d anticipated. Just a week or two later a longtime friend who knew of my interest in technology called to ask if I’d join him in meeting some friends who wanted to create an Internet service provider site. Several days later I met Jim Southworth, a primary sponsor of the idea, at his home, along with several highly skilled computer specialists. Most of them were younger and fully employed; but the idea of establishing and operating our own ISP, on a voluntary basis, excited all of us.

We quickly drew up a plan whereby these skilled computer technicians would run the internet service provider (ISP), taking turns monitoring our equipment. Some of them even donated their own computers, while two of us made interestfree loans to purchase the specialized equipment required. Soon NOVA.org was up and running out of a spare room in Jim’s office building. Initially, the members of our small group were its only customers.

Not too long thereafter, Jim changed employers, so we had to find a new site for the equipment. Eventually, the Fairfax County public access TV station agreed to house us in Merrifield, Virginia. Our ISP’s reliability improved, and our customer base grew rapidly.

My colleagues encouraged me to run for a seat on the Fairfax Public Access Board of Directors. I was elected and served for several years, ultimately becoming president of the board. NOVA.org soon became an integral part of Fairfax Public Access.

As president of the Fairfax Public Access Board, I initiated and negotiated FPA’s purchase of its building, located in an area that was about to undergo a major renewal. There was considerable resistance from some board members when I proposed that we buy the building. Then, once I had the majority of the FPA board in agreement, there were members of the county Board of Supervisors to convince. I spent a good hour before the County Board of Supervisors explaining our reasons for buying the building. Finally, after explaining that our doing so would not cost the county a dime, the board gave me the green light to proceed with the purchase.

Within a week our treasurer and I met at the building owner’s law firm in Washington, D.C. With a reasonable mortgage in hand, the bank representative and I signed the papers, making Fairfax Public Access owner of the building. I’ve since been told that the resulting increase in value has enabled FPA to purchase and install some of the latest broadcast technology in its studios and control rooms.

To this day, I use my email address, powers@nova.org, with pride.

Read More...

- “What We’re Doing Now” (The Foreign Service Journal, May 2016)