Redesigning Foreign Service Performance and Promotion at USAID

USAID took the first bold step to modernize its performance management and promotion systems in 2014, asking FSOs to report honestly and in detail what they thought of these processes.

BY MARTHA LAPPIN

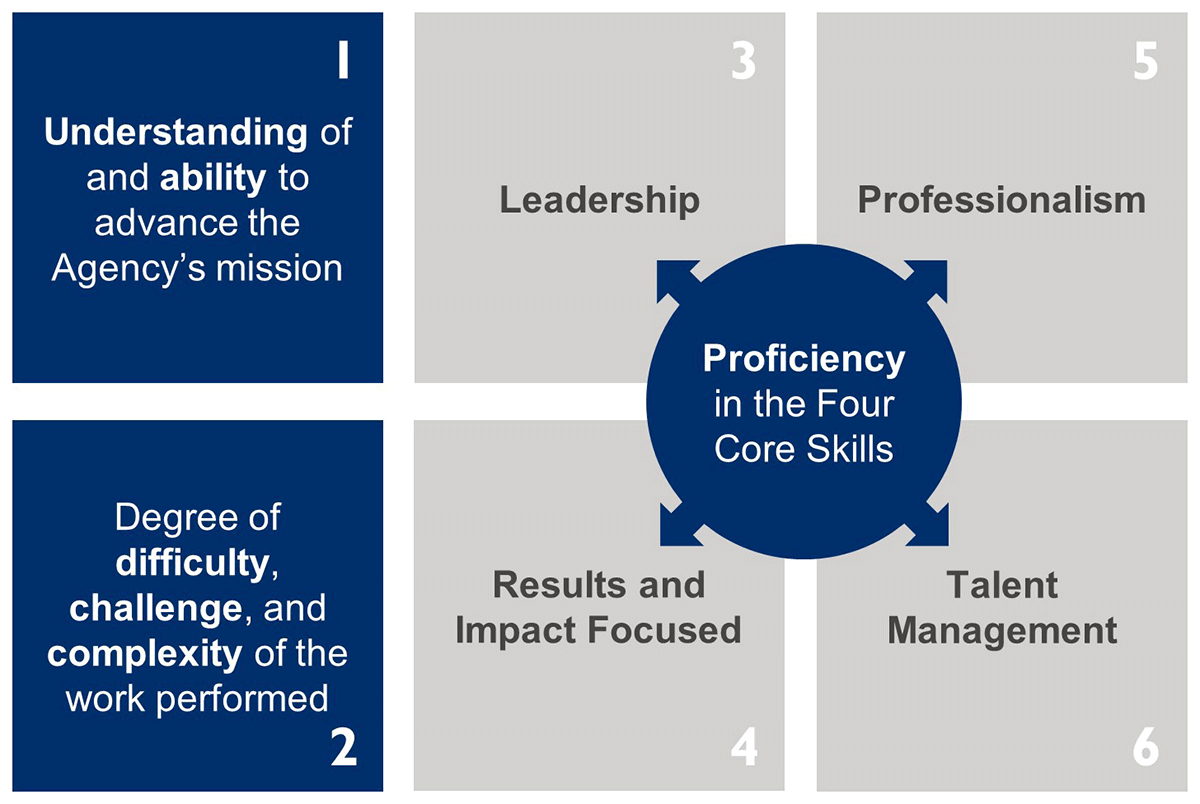

The Six Promotion Decision Factors

Courtesy of Martha Lappin

In 2014 USAID took the first bold step on a journey to modernize its performance management practices and increase the transparency and fairness of its promotion process. The Office of Human Capital and Talent Management asked Foreign Service officers to tell us honestly, and in great detail, what they really thought of the agency’s performance management and promotion processes (USAID FSOs number 1,850, compared to 7,905 at State). The results, published in 2015 in “Current State Report: Evaluation of the USAID Foreign Service Performance Management Program,” were not a surprise; they reflected the complaints, frustrations and growing cynicism about processes FSOs had been sharing with each other and their leadership for years.

What was new, and also exciting, was the agency’s commitment to do something about it. All we knew at the time was that Band-Aids and quick fixes wouldn’t suffice, and that FSOs themselves would have to play a leading role in overhauling an outdated and inefficient system.

Here are the changes USAID has implemented to date, as well as some of the lessons learned in the process.

Identifying the Problem

Federal mandates established by the Foreign Service Act of 1980 provide the foundation for FSO performance management and promotion policies. Advancement in the Foreign Service relies on a rank‐in‐person, competitive promotion system, supported by a traditional approach to planning, monitoring and evaluating performance. For decades, the cornerstone of both the performance management and promotion processes at USAID was the Annual Evaluation Form. The AEF served as both the annual performance evaluation, documenting how well the individual has done over the past year, and the primary input to the boards charged with recommending candidates for promotion. In theory, this might seem like an efficient way to “kill two birds with one stone”—however, in practice, the AEF served neither purpose well and consumed an inordinate amount of time every spring.

What we suspected, and our assessment confirmed, was that candid conversations about professional development were few and far between (and met with considerable resistance if they suggested that an employee’s performance wasn’t up to par in a particular area), and that the AEF had largely devolved into an exercise in artful writing designed to impress the promotion boards.

These and other findings reflect the fundamental problem with trying to use a single document for two very different purposes. AEFs tended to focus on the employee’s most noteworthy achievements and were often exaggerated and laden with superlatives that obscured true differences across employees’ skills and readiness for promotion. Moreover, it was never clear whose opinion the AEF reflected—although “officially” written from the supervisor’s perspective, employees often wrote the first (and sometimes final!) draft of their own AEF. And 360-degree feedback solicited at the end of the year was often reduced to quotes used to support supervisors’ glowing narratives.

The norms that evolved around AEFs over many years contributed to FSOs’ loss of confidence in the process, but that was not the only casualty. The single-minded focus on AEF writing every spring also undermined what should have been the primary goal of the performance management system—namely, helping FSOs develop and enhance the many complex skills they need to be successful as they move up the career ladder. When performance management is viewed as synonymous with writing AEFs, things like thoughtful conversations about performance, honest feedback about strengths and weaknesses, and deliberate efforts to create developmental assignments tend to take a back seat.

This doesn’t mean that most supervisors didn’t care about developing their staff. Many supervisors tried to maintain a focus on employee development, including holding employees accountable for poor performance, but our human resources systems provided little support for their efforts. With too few people and too much work to do, it was just too easy for meaningful conversations between employees and supervisors to get sidelined or postponed indefinitely.

Putting Employee Development into Performance Management

As HCTM made a commitment to acknowledge, understand and address these challenges, we were extremely fortunate to have the full support of USAID’s senior leadership—including our administrator, our partners at AFSA and, most important of all, our hardworking 18-member community of stakeholders (CoS). Beginning in April 2016, the CoS that led the redesign consisted of FSOs from the FS-3 to Senior Foreign Service grades. The group was co-chaired by the USAID counselor, the highest career FSO at the agency, and an FS-3 officer. The role of the junior officers was particularly important because we sought to build to the future.

The goals of the redesign were:

- Facilitate ongoing, meaningful feedback and professional development to build employees’ expertise throughout their careers.

- Ensure that processes for dealing with employee misconduct and chronic poor performance are clear, fair and effective.

- Increase the transparency, objectivity and fairness of the promotion process.

- Reduce complexity and administrative burden, wherever possible.

HCTM supported the stakeholder community by providing input from the latest research and standards of practice in both the public and private sectors, and by facilitating the many working groups that discussed, debated and, ultimately, designed the framework for the interrelated elements of the new processes. Forms, instructions and operational details were developed and refined through focus groups, field tests, negotiations with AFSA and a three-day promotion process pilot test. This collaborative, data-driven approach produced systems that are practical as well as innovative.

The Annual Evaluation Form had largely devolved into an exercise in artful writing designed to impress the promotion boards.

The first task the stakeholder group tackled was to integrate the FS Skills Matrix and the SFS Skills Model into what is now our FS/SFS Skills Framework. The differences across the FS and SFS core skills and subskills suggested that, suddenly, as one entered the SFS different skills were required, when in fact what our working group determined was that skills required for success are the same; what changes is the expected level of proficiency and the sphere of influence and context in which the critical skills are demonstrated.

The FS/SFS Framework now provides a solid foundation for both performance management and promotion processes across an individual’s career at USAID. In addition, the behavioral examples developed to illustrate how expected proficiency levels in the four core skills change as FSOs progress in their careers help both supervisors and promotion boards anchor their expectations.

Next, stakeholders charted a vision for what our performance management system should look and feel like. We named the new system “Employee Performance and Development,” leaving no doubt that developing our people was the primary objective. The actual requirements of the system are minimal, yet the redesign represents a major shift in our culture—from a focus on end-of-year documentation to year-round conversations. Here are the new requirements:

- Quarterly conversations between supervisor and employees.

- Skill development objectives, along with performance/task expectations, for every FSO.

- A skills assessment review and discussion conducted by supervisors at the end of every performance appraisal cycle.

- A satisfactory/unsatisfactory end-of-year evaluation, with no written narrative.

- An Annual Accomplishment Record consisting of five entries of 75 words (or fewer) where employees summarize their contributions to the team or mission and then supervisors review, suggest revisions if appropriate and sign.

- Counseling and Performance Improvement Plans for under-performers.

Training and guidebooks highlight the importance of honest two-way conversations about progress, performance and priorities. They emphasize supervisors’ responsibility to employees’ advancement by developing their own coaching, feedback and communication skills. And they underline the need for supervisors to seek and share timely, relevant and development-oriented 360-degree feedback on the people they supervise throughout the year.

All of these changes were rolled out and communicated to the USAID workforce in 2018 and 2019, along with the promise that every element of the new process would be evaluated—and refined—in the coming years based on employee feedback. The Year One Evaluation was comprehensive, including promotion board member interviews and surveys, as well as an October 2019 Workforce Survey completed by more than 500 FSOs (representing nearly one-third of the FS USAID workforce).

We have learned that we are clearly on the right track, but still have work to do. The good news is that two-thirds of our respondents reported having had both required quarterly conversations in the first two quarters of the appraisal cycle. Given all the summer assignment transitions, these are pretty good numbers; however, there is room for improvement in how quarterly conversations are used.

Only half of all FSO respondents felt that their supervisor had “used quarterly conversations effectively to clarify expectations and priorities”; and only half said they had established a skill development objective with their supervisor. This year, HCTM and senior leaders need to do a better job communicating the value of skill development objectives. These objectives not only keep attention focused on specific developmental goals; they also create relatively nonthreatening opportunities to practice the art of asking for, giving and acting on constructive feedback. Nevertheless, it is encouraging that fully 85 percent of our respondents agreed that quarterly conversations were a good investment of time for employees and supervisors.

Promotions

The changes to the promotion system were even more dramatic than the changes to our performance management processes. In rethinking what boards need to see to make wise promotion recommendations, the stakeholders group recognized that boards need more than just one perspective (the supervisor’s), and they need input that would more clearly differentiate FSOs. After much discussion and debate, the group determined that promotion boards would need three different documents to reliably assess the best candidates for promotion:

- The Annual Accomplishment Record (completed by all FSOs as part of the Employee Performance and Development process).

- A Promotion Input Form, consisting of five 250-word blocks employees complete and one 250-word block supervisors complete to help boards assess candidates on the six promotion decision factors [see the graphic, above].

- Multisource Ratings (MSRs) of behaviors that reflect the four core skills, collected from supervisors, colleagues and subordinates.

The Annual Accomplishment Record is designed to provide a fairly objective account of the employee’s significant contributions and accomplishments over the course of the appraisal period. It is written by the employee with input from the supervisor, who also has to sign off on its accuracy. The new Promotion Input Form asks employees to describe how they have demonstrated each of the four core skills (these are four of the six promotion decision factors), and to also show their understanding of and ability to advance the agency’s mission.

Supervisors have just one block to complete, and this is where they can recommend or not recommend someone for promotion, and share what they believe the promotion board needs to know to accurately assess the employee on the six promotion decision factors.

We named the new system “Employee Performance and Development,” leaving no doubt that developing our people was the primary objective.

Multisource Ratings: How They Work

The promotion process also involves collecting data from multiple sources on the extent to which promotion-eligible FSOs are displaying specific behaviors related to the four core skills. This information is collected via short surveys where respondents use a five-point scale to rate the extent the FSO does things like “seeks information from relevant sources to develop and implement appropriate solutions when problems arise” and “communicates effectively and respectfully with people at all levels of USG and host country.” These Multisource Ratings are completed by the FSO’s immediate supervisor and all direct reports, if they have any. Ratings are also collected from a carefully selected group of colleagues.

Supervisors are instructed to meet with their promotion-eligible FSOs to review the clearly defined criteria for peer/other raters and identify which colleagues in the pool of potential raters best meet the criteria. The goal is to only include individuals who have a strong working relationship with the FSO and thus are in a position to have observed most of the behaviors they are asked to rate. The peer/other and subordinate ratings are aggregated across the individuals in those groups, and averages are only shared with FSOs if there are at least three respondents in the group. This is to preserve the confidentiality of the peer/other and subordinate ratings—one of the most critical elements of the process. Supervisor ratings are not confidential.

Summaries of the MSRs are provided to promotion candidates to support their professional development, as well as to the promotion boards.

Of the three new components of the promotion package, the Multisource Ratings are the most controversial. The anxiety and confusion over them are reflected in the fact that when asked if including the ratings in the promotion process would help boards better assess candidates’ core skills, more than 40 percent of the October survey respondents said no. The survey also revealed some possible reasons for this skepticism. For example, average ratings, particularly from supervisors, were very high; and most FSOs did not believe the five-point scale was adequate to differentiate candidates. We also noted that too many supervisors (approximately 15 percent) failed to follow the rater selection process and guidance, and that the large number of peer raters we allowed (up to 15) encouraged including raters who did not truly meet the selection criteria.

The Office of Human Capital and Talent Management is addressing each of these issues. For example, we are using item analyses to identify those that are “too easy” and fail to adequately differentiate FSOs. We are also modifying the rating scale anchors and reducing the maximum number of peer and subordinate raters from 15 to 10. The other major focus for 2020 is communication. Only 60 percent of our FSO respondents said their supervisor encouraged the team to participate in the MSR process, and only 50 percent said their supervisor reinforced the need for honesty, confidentiality and integrity in the MSR process. As we develop better training, and as supervisors and managers get more comfortable with the rating process, we expect confidence in the MSRs to increase, as well.

Overall, we were very encouraged to learn that nearly all promotion board members endorsed the value of the new promotion package. And while many FSOs are adopting a wait-and-see attitude about MSRs and the overall impact of the new process, a large majority see it as an improvement over the old evaluation forms.

A Step Forward

In summary, the innovations USAID implemented in 2018 and 2019 represent a huge step forward in the agency’s effort to enhance the skills and professional development of the workforce while simultaneously providing promotion boards with the information and structure they need to identify the best candidates for promotion. There appears to be widespread acceptance of the Employee Performance and Development process, although we need to continue to encourage and support supervisors to use the required quarterly conversations more effectively. To that end, we have provided extensive education and training opportunities for the new process, and have been delivering a course on critical conversations.

With respect to the new promotion process, acceptance may take a little longer. Understanding the new process requires unlearning the deeply embedded norms and practices of the AEF system, and this takes time. It also requires the Office of Human Capital and Talent Management to continue to work on training and communication, in addition to paying close attention to the one-off situations, technology issues, and equity and fairness concerns our workforce is sharing with the office and with AFSA.

Fortunately, our workforce is a partner in this great endeavor, and with their continued good faith efforts to make it work—and to provide honest feedback when things aren’t working—our personnel systems will only get better. We are already looking forward to hearing what FSOs will tell us in the Year Two Evaluation.