You Have a Strategy. Now What? — How to Turn Any U.S. Mission Strategy into Results

Today State has a unique opportunity to reassert leadership of foreign policy by focusing on delivering the outcomes promised by strategies that are now aligned across the department.

BY MATT BOLAND

Why is it that some chiefs of mission and deputy chiefs of mission are better than others at turning policy ideas into results? How do some seem to project a command presence—providing overall direction, interagency coordination and leadership of U.S. foreign policy in country—while others do not? After all, they are just like chiefs of mission and deputy chiefs of mission (DCMs) everywhere: they have access to the same mission-driven workforce, they struggle against the same outdated State Department technologies, and they face the same pressure to react to events and respond to taskings from D.C.

As it turns out, however, they all follow much the same routine. Many great government leaders think, act and communicate in similar ways. The best leaders at State follow these practices, and we would all benefit if more leaders did so.

The need to improve strategic planning and implementation has been highlighted in every major State Department reform initiative since 1992. One problem is that many at State believe they have “policy” responsibility, while “strategic planning” and “implementation” are, they think, someone else’s concern. The result of such a mindset was summed up in the State-USAID reform plan submitted to the Office of Management and Budget last September: “Failure to prioritize top foreign policy objectives and plan strategically has led to ad hoc decision-making, ineffective allocation of human and financial resources, and disjointed activities at the Washington and mission levels.”

In fact, when it comes to delivering results, strategic planning and implementation are not only inseparable from policymaking, but are its driving force. As Michael Barber, first head of the U.K. Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (an institution created to strengthen the British government’s capacity to deliver on Prime Minister Tony Blair’s policy priorities), puts it: “Policy is 10 percent and implementation is 90 percent.”

Today we have a unique opportunity at the State Department to reassert leadership of foreign policy by focusing on delivering the outcomes promised by our strategies. It is an opportune moment for action—what the Greeks call kairos—because we now have coherent strategies across the department. Drawing on the new National Security Strategy, the State-USAID Joint Strategic Plan was finalized in February; that was followed by completion of 46 bureau strategic plans this spring, and integrated country strategies (ICS) for 185 U.S. missions this summer.

Having set clear objectives, developed plans to achieve them and aligned strategies across the State Department, leaders and staff are poised to achieve significant results in advancing American security, interests and values. Here are some suggestions for how to take advantage of this opportune moment.

Build a Strategic Planning and Implementation Process That Delivers Impact

The key to delivering on any strategy is to understand what prevents effective strategic planning and implementation, and then to attack those challenges head on. This is as true for a government official in Britain or Indonesia as it is for an official of the U.S. State Department.

During a yearlong fellowship at The Boston Consulting Group, a global management consulting firm with more than 50 years of experience as a leader in strategy, I had the opportunity to be part of a team that worked to identify such obstacles. We interviewed 31 current and former government leaders around the globe. In a separate project, I interviewed a dozen State Department officials—chiefs of mission, DCMs, Foreign Service officers and Civil Service professionals—to benchmark the State Department’s approach to strategic planning and performance management against global best practices.

Strategic planning and implementation are core leadership responsibilities.

Our work pointed to key steps mission leaders and staff can take to become more effective at developing and implementing their strategy. There are several obstacles to overcome at the State Department:

A “fire-fighting” and risk-averse culture. Reacting well to unplanned and unforeseen events and crises is some of the most important work we do. However, effective leaders also proactively shape the future rather than simply react to it by setting and driving an agenda. Further, if we avoid taking reasonable risks for fear of failure, we won’t get big things done.

Lack of leadership engagement. While many department leaders have policy expertise and focus, they often delegate responsibility for strategic planning and implementation to others. This lack of engagement at the top filters down, leading to members of the mission who don’t fully understand or aren’t committed to implementing the strategy.

High turnover. Foreign Service officers transition every two to three years, and the average tenure of a Senate-confirmed appointee is only 18 to 30 months. With little time to make a mark, many understandably focus on short-term initiatives, rather than long-term goals and objectives.

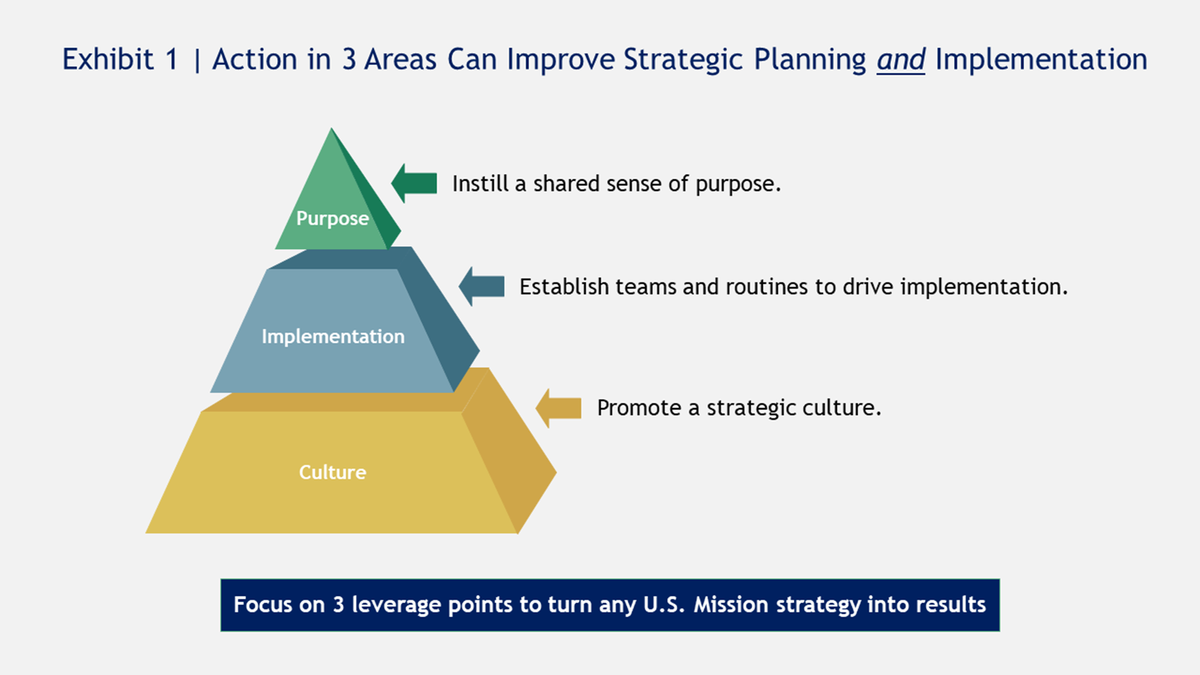

Based on our interviews, we identified three actions that chiefs of mission and DCMs can take to mitigate these challenges and turn the mission strategy into results: promote a strategic culture, instill a shared sense of purpose, and establish teams and routines to drive implementation (see graphic above).

Promote a Strategic Culture

To ensure a shift in the culture—habits, hearts and minds— chiefs of missions and DCMs must participate in strategic planning, frontline leaders at post must be involved from the start, and the risk-averse mindset at State must be addressed.

Strategic planning and implementation are core leadership responsibilities. Effective chiefs of missions and DCMs personally drive the effort to set strategic priorities, build buy-in, align resources, communicate the strategy consistently and hold people accountable for executing the plan. “Strategy is ultimately the leader’s responsibility,” according to Salman Ahmed, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama and senior director for strategic planning. “You can’t delegate responsibility for leading change.”

When she served as DCM at Embassy London, Ambassador Barbara Stephenson (now the president of AFSA) used strategic planning as a platform to break down section and agency silos, build ownership and organize a whole-of-government approach. She led a strategy development process that involved staff from across the mission in the effort. “We deliberately designed mission objectives that required an interagency team to deliver them,” Amb. Stephenson told me. “This created a clear sense of where we were going, why, and the role each section and agency plays in achieving our objectives.”

The single most important step chiefs of mission and DCMs can take to promote a strategic culture is to draw frontline leaders—the section and agency heads who supervise frontline employees at post—into the effort. Why?

First of all, that’s where the work gets done. Frontline leaders can elevate to the attention of senior leadership the practical realities of implementing a particular strategy, making successful implementation more likely. “If a team is closely involved in developing the strategy they will feel ownership of it,” Paul Gerrard, director of policy & campaigns at the Co- Operative Group, told me. “If they feel ownership, then they will want to make it work.”

Second, it affords the greatest leverage and promises the most impact. Since the majority of staff at post reports to a section or agency head, these leaders have an outsized impact on shaping the culture, allocating resources and ensuring that the day-to-day actions of the workforce are aligned with the mission’s objectives. Moreover, it helps develop mid-level staff members who are likely to be the next generation of leadership.

The bottom line: The best way to link strategy with implementation is to ensure that the same people work on both.

It’s important to find ways to reward and protect those who take reasonable risks but achieve less than positive results.

In addition, it’s important to find ways to reward and protect those who take reasonable risks but achieve less than positive results. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo underscored this when he addressed employees at a May 16 town hall: “I’m prepared to accept failure. … I will be with you. If we’re doing things right and we have an effort and it is right, and it doesn’t work, know that’s acceptable—indeed, at some level, encouraged. If there are no failures, I guarantee you we’re not out working hard against these problem sets.” The risk-averse mindset that the department cultivates can undermine the implementation of any given strategy.

Instill a Shared Sense of Purpose

One of the chief of mission’s most powerful levers is to mobilize the mission around shared objectives. Foreign Service officers are mission-driven. The ember burns deep within them; all leaders have to do is fan it. If they can ignite a sense of purpose that ripples across the mission, the results will be transformative. Employees will engage in deep learning, take risks, innovate and make meaningful contributions.

Chiefs of mission and DCMs can build a purpose-driven U.S. mission by following three steps:

1. Articulate a clear vision. Ambassadors should articulate a compelling vision for advancing the mission over the next three to five years. This will provide critical energy and direction for the mission. “Vision isn’t everything, but it’s the beginning of everything,” as David McAllister-Wilson, president of Wesley Theological Seminary, puts it.

2. Stay focused on the mission objectives. This may seem obvious, but it is incredibly difficult for officers to stay focused on the mission objectives because of the daily pressure to react to events and respond to requests from Main State and home agencies.

Ronald E. Neumann, who served as ambassador to Afghanistan, Bahrain and Algeria, tackled this problem by providing ‘top cover’ so that officers could and would say no. He said, “I told my staff: ‘Instructions come only from me or in front channel cables. Anything else is a request. If you think a request is wrong or will get in the way of something I told you to do, come see the DCM or me.’ If we didn’t want to accommodate the request, I would tell the officer to message back, ‘I can’t follow your instruction because the ambassador says no, but he said you can call him to talk about it.’ The phone never rang.”

3. Constantly communicate the vision and objectives. Every mission’s integrated country strategy needs a consistent communications effort if it is to succeed. Once leaders at the top and in the middle have internalized the strategy, they must help frontline employees see how it connects with their day-to-day work.

The key to delivering on any strategy is to understand what prevents effective strategic planning and implementation, and then to attack those challenges head on.

Successful missions do things like the following:

Discuss progress on the strategy at every country team meeting. For example, at every country team meeting at the U.S. mission to India, former five-time Ambassador Nancy Powell asked people to cite an achievement from the previous week or an upcoming challenge linked to a mission objective.

Require action memos to link proposals to the mission strategy. “When a section or agency sends a decision memo asking the chief of mission or DCM to participate in something,” DCM Eric Khant says, “it should demonstrate how the leader’s participation will help advance mission objectives.”

Communicate success stories in a monthly front office newsletter, including how the work of staff members contributed to mission goals or eliminated obstacles to achieving key mission objectives.

Organize a “look back and look ahead” town hall, where the ambassador reviews mission progress over the past six months and the key objectives for the next six months. When the strategy is continually reinforced through such meetings and onboarding “check-ins” for newly arrived employees, training sessions and other forums where people at all levels ask questions and share ideas, it draws their support.

Create ICS communications materials to raise awareness. Here’s one great example: The U.S. missions to Burma, Mauritania and Uruguay each developed and disseminated a collection of integrated country strategy (ICS) communications materials. Mission goals and objectives were prominently displayed on the intranet site and printed—in English and the local language—on wallet-sized cards, desk cards and posters. These materials were displayed in high-traffic areas within the embassy and could also be included in welcome kits.

Establish Teams & Routines to Drive Implementation

Once the mission strategy is developed, chiefs of mission, DCMs and the country team need to know—on a routine basis— how well the mission is implementing the plan and delivering the outcomes it promises. I recommend the following three-part framework for implementation:

1. Establish mission goal or objective teams. Unless it’s someone’s job, it’s no one’s job. At the heart of successful implementation of the country strategy are mission teams focused on helping achieve its objectives. They can help ensure that the mission has clear, measurable and outcome-oriented objectives. They can also ensure that programs to implement the ICS outline how the program will contribute to objectives, how progress and performance will be measured and tracked, and how the program will be evaluated. These teams should include Locally Employed staff and be the people at post the chief of mission and DCM can count on to be largely resistant to the crises of the moment, even when the front office has to respond to them.

2. Collect performance data. Doing an effective job of implementing and adjusting the strategy hinges on having the right data. Among the best tools within the ICS are the performance indicators and milestones, which create a link between the mission’s strategy and the expected outcomes.

3. Use routines to drive and monitor implementation. Having set the mission strategy, it is essential to establish implementation routines. Three simple but powerful routines create deadlines and a sense of urgency for the mission to deliver results. The first is a regular rhythm of strategic dialogues between the chief of mission, the DCM and the country team to review progress on implementation of the strategy, discuss and solve major challenges, and make decisions to drive implementation forward. The second and third are annual strategic reviews and quarterly strategy check-ins (see chart below).

For example, when a U.S. embassy in Asia wanted to paint a mission-wide picture of what was working, what wasn’t, and why, it launched a strategic review designed to test the integrated country strategy assumptions, measure progress and identify challenges. The review showed progress toward ICS goals and led the country team to conclude that remaining results-oriented sometimes means terminating programs that are not working productively toward mission goals.

The U.K. Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit used implementation routines to focus relentlessly on four disarmingly simple questions: What are you trying to do? How are you planning to do it? At any given moment, how will you know if you’re on track to succeed? If you’re not on track, what are you going to do about it?

Effective Leaders Own the Mission Strategy

To marshal action on their priorities, we see successful chiefs of mission and DCMs spend time on their integrated country strategy. They adapt it, communicate it, reinforce it and help people see when they may be drifting from it. Employees recognize their commitment to the strategy, begin to believe in it themselves and reorient. The change starts at the top and spreads across the mission. As former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy told me, “If the leader owns strategy from the start, communicates it clearly, rewards people for executing it and holds them accountable when they don’t, that’s the most powerful way to mobilize an organization.”

Good strategy is not about drafting the perfect plan on paper. It’s about giving employees clear objectives, empowering them to lead and fostering a culture of continuous improvement in order to achieve greater mission impact. As Secretary Pompeo urged at his town hall in May, “People talk about delegating authority. I want you out there demanding it. Say ‘I have this. I can take on this task. I’ll keep you informed, I’ll seek your guidance, and then I’ll go execute the heck out of it!’”

To learn more and access resources and tools for strategic planning and performance management, State Department employees can visit the Managing for Results intranet site at cas.state.gov/managingforresults.

| Establish Routine Reviews | Annual Strategic Review In-depth assessment of progress on all mission objectives |

Quarterly Strategic Check-Ins Snapshot of progress on select mission objectives |

|---|---|---|

| What & Who | State Department guidance requires…

|

In addition, best practice recommends…

|

| The Benefits |

|

|