Once Upon a Time: The U.S. Consulate in Martinique

After a storied history of nearly two centuries, the consulate in Fort-de-France closed its doors in 1993.

BY SÉBASTIEN PERROT-MINNOT

The U.S. consulate in Fort-de-France in 1902.

Charles W. Blackburne / International Center of Photography

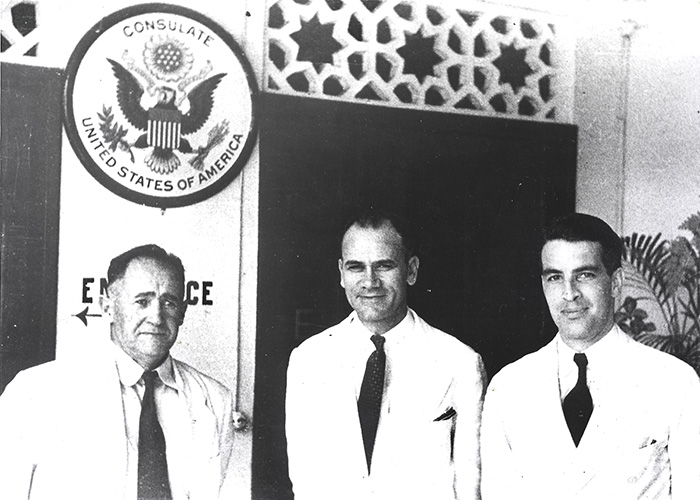

From left: Naval observer Commander Ernest J. Blankenship, outgoing Vice Consul Vinkler Harwood Blocker, and incoming Vice Consul Robert Sheehan, at the U.S. consulate in Fort-de-France, on July 18, 1941.

Acme / FK (Photo Property of the Author)

Thirty years ago, the U.S. consulate general in Fort-de-France was closed by decision of the State Department, evoking some emotion in Martinique and beyond: the United States had developed a special relationship with this territory of the French West Indies, where it had consular representation for more than two centuries.

The U.S. consulate in Fort-de-France was located in the heart of the city. In 1949 the U.S. government acquired a beautiful art deco villa in Didier, in the heights of the city, for the residence of the heads of mission.

The consulate was formally attached to the U.S. embassy in France, and its district evolved over time to finally include Martinique, Guadeloupe (with St. Martin and St. Barthélemy), and French Guiana. After World War II, the consular mission was elevated several times to the rank of consulate general, which it had when it was closed.

The State Department’s April 1984 “Martinique Post Report” noted that the American community in Martinique was “small” and described the official functions of the consular staff as follows: “The principal officer has traditionally played a fairly visible role in local official, business, and cultural circles; ceremonial and representational responsibilities are demanding. In relation to its size, the Consulate General receives a significant number of U.S. Navy ship visits and individual visits of U.S. officials, which usually require official representation. The consul general has certain representational responsibilities; the vice consul has relatively few.”

Positions at the consulate were highly valued, according to testimonies. John J. Maresca, for example, who was appointed consul general in 1977, spoke in his 2016 memoirs of a “dreamlike assignment” and eloquently expressed the disappointment he felt when his assignment was revoked in extremis.

An Origins Story

Walter S. Reineck, U.S. consul in Fort-de-France from 1925 to 1929.

Courtesy of Lili Reineck Ott

Created by President George Washington in 1790, the U.S. consulate in St. Pierre, which was then the economic and cultural capital of the French colony of Martinique, was among the first 10 diplomatic and consular posts opened by the young North American republic. It was initially entrusted to Fulwar Skipwith, who served under difficult conditions in the midst of the French Revolution and left the island in 1794 as it began to be occupied by the British.

Later, the U.S. government appointed agents to represent its interests in the colony, which was returned to France in 1802. Yet it was not until 1815 that a consular presence was reestablished, with the installation of John Mitchell in St. Pierre. From then on, the U.S. consuls in Martinique succeeded one another in the “Little Paris of the Antilles” until 1902.

Disaster Strikes

On May 8 of that fateful year, Mount Pelée erupted, unleashing one of the worst volcanic disasters in modern history. The city of St. Pierre was destroyed, and nearly 30,000 people died, including Mayor Rodolphe Fouché, Governor of Martinique Louis Mouttet, and consular officials serving the interests of the United States, Great Britain, the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, the Netherlands, Italy, and Belgium.

Among the victims were U.S. Consul Thomas T. Prentis and Vice Consul J. Amédée Testart G.; they were later honored by the Department of State, the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA), American engineer and volcanologist Frank Alvord Perret, the U.S. embassy in France, and the Municipality of St. Pierre (see the May 2020 FSJ, “The Unlucky Consul: Thomas Prentis and the 1902 Martinique Disaster” by William Bent, and the November 2022 FSJ, “Memorializing the U.S. Consular Presence in Martinique” by this author).

The U.S. consulate in St. Pierre was among the first 10 diplomatic and consular posts opened by the young North American republic.

With no news from his colleagues in Martinique, the U.S. consul in Guadeloupe, Louis H. Aymé, went to St. Pierre on May 10, 1902. He saw the general disaster and noted the disappearance of the American consular officers. A few days later, the American naval ships USS Potomac and USS Cincinnati reached the martyred city. Their crews explored the ruins of the consulate with the authorization of the colonial government of Martinique but did not manage to identify the bodies of Prentis and Testart. Under these circumstances, Aymé assumed the duties of acting consul in Martinique, setting up his office in Fort-de-France, the colony’s capital.

The May 8 disaster was big news in the United States, where it generated a broad movement of solidarity. The U.S. government provided prompt and substantial aid to Martinique, with the invaluable on-site assistance of Aymé.

In June 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed a new consul to Martinique: John F. Jewell, who took his post in Fort-de-France. Jewell’s first successors were Chester W. Martin (1906-1908), George B. Anderson (1908-1910, who died of disease while on assignment, during a stay in the United States), and Thomas Ross Wallace, who remained in office for a record 14 years (1910-1924).

Presidents François Mitterrand and George H.W. Bush at Habitation Clément, Martinique, on March 14, 1991.

Fernand Bibas / Collectivité Territoriale de Martinique

The Two World Wars and in Between

The consulate was on alert during World War I, but the State Department did not identify any real threat in Martinique. During the 1920s, however, the American envoys faced hostility from the Martinican population because of persistent rumors announcing the sale of the island to the United States.

Despite this, they tried to promote trade in a context of global economic growth. The consul in Martinique from 1925 to 1929, Walter S. Reineck, noted the tourist potential of the Lesser Antilles. “In all probability, the West Indies will become more and more a winter playground for Americans and Canadians,” he declared in a speech delivered in 1928 or 1929, according to the Reineck family archives. In the following decade, with the active support of the consulate, Pan American Airways seaplanes began to fly to Martinique and Guadeloupe.

Martinique’s strategic interest for the United States increased dramatically in June 1940, following France’s unexpected defeat by Nazi Germany. France’s new political regime, the Vichy regime—which was officially recognized by the United States—embarked on a path of collaboration with the Third Reich. The government of Franklin D. Roosevelt feared that Germany would take advantage of the French territories in the Americas to carry out hostile actions against the United States and seize the gold of the Bank of France that had been sent to Martinique in June 1940.

A military occupation of Martinique, where most of the French armed forces in the Americas were concentrated, was considered by the Roosevelt administration. The plan was finally discarded, thanks to the “gentlemen’s agreements” concluded between Admiral Georges Robert, high commissioner for the French territories in the Western Atlantic (based in Martinique), and Rear Admiral John W. Greenslade, senior member of the General Board of the U.S. Navy, in August and November 1940. The “Greenslade-Robert Agreements” guaranteed the neutralization of French forces in America, the securing of the gold stored in Martinique, and limited U.S. surveillance of the island, with the U.S. agreeing, in return, to supply the French colony with food, fuel, and raw materials. These provisions considerably strengthened the role of the American consulate in Fort-de-France, to which a naval observer was now attached.

Martinique’s strategic interest for the United States increased dramatically in June 1940.

On Dec. 8, 1940, while conducting an inspection cruise in the West Indies aboard the USS Tuscaloosa, President Roosevelt approached within about three miles of the coast of Martinique. He summoned the U.S. consular representative, Vice Consul Vinkler Harwood Blocker, and the naval observer, Commander Ernest J. Blankenship, to inquire about the situation in Martinique and Guadeloupe, and to relay specific requests to Admiral Robert. Roosevelt insisted, on this occasion, on the need to prevent any Nazi control and influence in these French territories.

The Greenslade-Robert Agreements, confirmed after Germany’s declaration of war on the United States on Dec. 11, 1941, were fairly faithfully executed by both parties. They were implemented with the essential assistance of the U.S. consulate, whose diplomatic activity was combined with intense intelligence and analytical work. The consular mission was also very busy with the European refugees who arrived in Martinique and wished to immigrate to North America. Appointed consul in Fort-de-France in 1941, and then consul general the following year, Marcel Etienne Malige (a fluent French speaker who was born of French parents who immigrated to the United States) played a crucial role in American policy toward Martinique and Guadeloupe at this time.

The panorama changed with the severance of diplomatic relations between the United States and the Vichy regime in November 1942. Five months later, in April 1943, Washington denounced the agreements made with Admiral Robert, recalled Malige, and put an end to American assistance to the French West Indies, leading to a worsening of shortages in these territories. The consulate in Fort-de-France nevertheless remained open and was entrusted to a consular officer whose activities were to be strictly limited to “the protection of American interests” and exclude “any negotiations of a political character,” according to a State Department note dated May 1, 1943.

This situation was short-lived, however. In July, after Henri Hoppenot, a representative of the French Committee of National Liberation, arrived and took power in Martinique, Malige was sent back to Martinique, and the United States restored its aid to the French West Indies.

The U.S. Consulate Office Building in Fort-de-France in 1983. This building, which still exists today, is located in front of the Saint-Louis Cathedral.

U.S. Department of State / National Archives

The Long Cold War

This villa is where the head of the U.S. consular post resided, in the Didier suburb of Fort-de-France, 1993.

Courtesy of Henry Ritchie

World War II was followed by the Cold War, which led the American consuls in Martinique—a French department since 1946—to pay special attention to the island’s social and “racial” problems, and their exploitation by the communists.

In 1946 Consul William H. Christensen wrote in a note to the State Department: “Hitherto the French had established a reputation as humanists where color was concerned. However, there is color prejudice in Martinique. Césaire, communist deputy [Aimé Césaire was also a famous writer and intellectual.—Au.], has made several appeals to electors by raising the color question. This appeal is based on the fact that the wealth of the island is concentrated in hands of whites whereas political power is entirely in hands of Negroes—in the case of Martinique, in the hands of negro communists.”

The consulate regretted at the time that the racial issue was being used by Martinican communists in their hostile propaganda against the United States, where segregation was still in effect. Washington could easily be seen as an ally of the economic oligarchy of the “békés,” the descendants of European colonizers who were worried about their future in the face of African Caribbean demands. In fact, in a 1946 report, Consul Christensen indicated that he had already been approached several times by white Martinicans who were asking for a U.S. military intervention in case of major unrest, and sometimes even for U.S. citizenship.

The Cold War crises in the Caribbean and Latin America had an impact on the U.S. consulate. In the tense atmosphere following the invasion of Grenada by a U.S.-Caribbean coalition in October 1983, the consulate was given police protection. On Nov. 1, a bomb exploded nearby, slightly damaging the building that housed the U.S. mission and a Chase Manhattan Bank branch, but not injuring anyone. The Caribbean Revolutionary Alliance (“Alliance Révolutionnaire Caraïbe” in French), an armed pro-independence group, claimed responsibility for the attack. At the same time, however, the consulate also gained sympathy through its economic, educational, cultural, and sports diplomacy. In the 1950s and ’60s, for example, it organized a very popular basketball cup with teams from Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Puerto Rico.

It should be added that the consulate participated in the organization of three summit meetings, which brought together French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and U.S. President Gerald Ford in Martinique in 1974 (to discuss mutual concerns in the international economic, financial, and monetary fields); President Giscard d’Estaing, U.S. President Jimmy Carter, British Prime Minister James Callaghan, and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in Guadeloupe in 1979 (to discuss various international issues, in particular the Iranian crisis); and French President François Mitterrand and U.S. President George H.W. Bush in Martinique in 1991 (for post–Gulf War exchanges).

The consulate also gained sympathy through its economic, educational, cultural, and sports diplomacy.

In the early 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, the French West Indies lost strategic importance. Besides, their American expatriate communities and trade with the United States remained relatively modest. It was in this context that the State Department put the consulate general in Fort-de-France on a list of diplomatic and consular posts to be closed in 1993-1994 for budgetary reasons.

The consulate, then headed by Consul General Raymond G. Robinson, closed its doors on Aug. 1, 1993, despite the mobilization of Martinican elected officials and the French government to try to avoid such an outcome. Martinican Deputy André Lesueur deplored the closing in the French National Assembly on Oct. 18, 1993: “This decision, in addition to the fact that it obscures the historical dimension of relations with the United States, is highly prejudicial to the French West Indies.”

The United States did, however, wish to maintain a consular presence in Martinique, and in 1993 the State Department opened a consular agency attached to the consular section of the U.S. embassy in Bridgetown, Barbados. This agency is still in operation.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- “The Unlucky Consul: Thomas Prentis and the 1902 Martinique Disaster” by William Bent, The Foreign Service Journal, May 2020

- “1902 Martinique volcanic disaster” by Sébastien Perrot-Minnot, Barbados Today, May 2022

- “Memorializing the U.S. Consular Presence in Martinique” by Sébastien Perrot-Minnot, The Foreign Service Journal, November 2022