Remembering 1989: Berlin Wall Stories

Diplomats reflect on the events that dramatically reshaped the postwar world.

A view of the east side of the wall at the Brandenburg Gate, where West Berliners perched atop the barrier taunt the East German police on Nov. 10, 1989.

Michael Hammer

Berliners at the Berlin Wall as it is being dismantled.

Michael Hammer

FSO Matt Bryza (center, in black jacket) and Margret Bjorgulfsdottir (spouse of Mike Hammer, next to Bryza) join Berliners in front of the Brandenburg Gate on Nov. 10, 1989, to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Michael Hammer

Right Place, Right Time

Michael Hammer

West Berlin, Federal Republic of Germany

Thirty years ago, fresh out of A-100 and on our first tours, my classmate Matt Bryza was serving in Poznan, Poland, and my wife, Margret Bjorgulfsdottir, and I were in Copenhagen. Matt and I had been friends in grad school at Fletcher and were eager to get together. Since Matt was serving in Poland in the bad old Iron Curtain days, he frequently went to decompress in West Berlin, so we decided to meet up there over Veterans Day weekend in 1989.

Little did I know at the time that it would be one of the most momentous experiences in my 30-plus years in the U.S. Foreign Service.

The journey got off to an inauspicious start. On the train from Copenhagen to West Berlin, an East German border guard took my diplomatic passport, barked something unintelligible and disappeared. Having seen too many spy thrillers, I thought this was it, we would be whisked away in darkness. But instead, he simply returned with deutsche marks in hand to reimburse me for a visa fee I should not have paid as a diplomat.

Things got funky when we arrived at Berlin’s train station and there was no sign of Matt, who had made all the arrangements for our visit. With no cell phone or way to reach him, we just waited anxiously until he came running, screaming: “They are tearing down the wall, they are tearing down the wall!” My immediate thought was that Matt must have been drinking. But, lo and behold, as we approached the Brandenburg Gate, you could hear the pounding of hammers against that hideous wall.

Without much thought, two American diplomats joined the young West Berliners on top of the wall. The West Berliners were taunting the East German guards, jumping onto the east side and then climbing back up on the wall as the guards, machine guns in hand, approached them. Thankfully, the East German guards did not fire as they had been prone to do previously when East Berliners daringly tried to flee.

I recall the lengthy lines at automatic cash dispensers as East Berliners collected the 100 DM they were entitled to upon arriving in the West. At border crossing points you could see Trabant car after Trabant car among crowds of people walking into the West, many with joyful tears streaming down their cheeks. As we strolled the streets, we ran into perhaps the only German we knew, another Fletcherite. Overcome with emotion, he uncharacteristically hugged us. That is the kind of day it was.

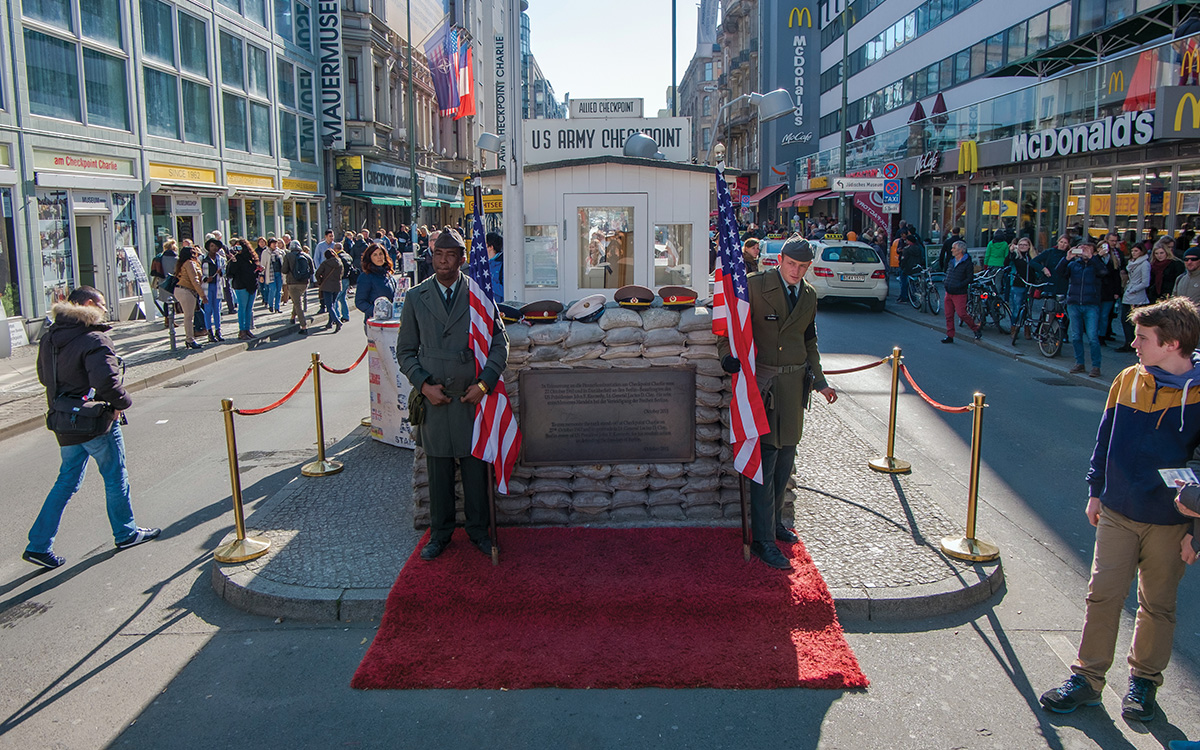

On Nov. 11, we had planned a dinner in East Berlin with our ambassador to East Germany, Dick Barkley, who had been a mentor to our A-100 class—the Fighting 44th! We called him to say we would understand if dinner was off, but he insisted we come over as his wife, Nina, was already preparing dinner. We crossed through Checkpoint Charlie, and as we looked at the endless stream of people crossing to the West, we worried how my wife, then an Icelandic citizen, would get back to the West. After dinner Amb. Barkley had to excuse himself to appear on “Nightline” to discuss the dramatic events. We took that as our cue to leave.

We sensed that the opening to the West would be permanent when we reached Checkpoint Charlie and saw that now the lines were of East Berliners returning to their homes, with virtually no one crossing westward. That night, the stench of cheap champagne flowing through the streets of Berlin was the smell of freedom—and how sweet it was!

I will admit to an uncomfortable moment when I returned to Copenhagen and shared my slides with the embassy community. The deputy chief of mission stopped me at one of the slides—an unobstructed view of the Brandenburg Gate?!—and asked where the photo had been taken. I quickly moved to the next slide, not wanting to dwell on the imprudence of exuberant American diplomats risking an international incident by climbing on top of the wall in celebration.

Michael Hammer was a first-tour Foreign Service officer in Copenhagen, on a vacation in West Berlin when the Berlin Wall fell. He is currently serving as U.S. ambassador to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

During the Cold War, a young West Berlin couple talks to relatives in an East Berlin apartment house (see upper window open). They have climbed to the top of the wall to have their brief conversation.

Getty Images / Bettmann

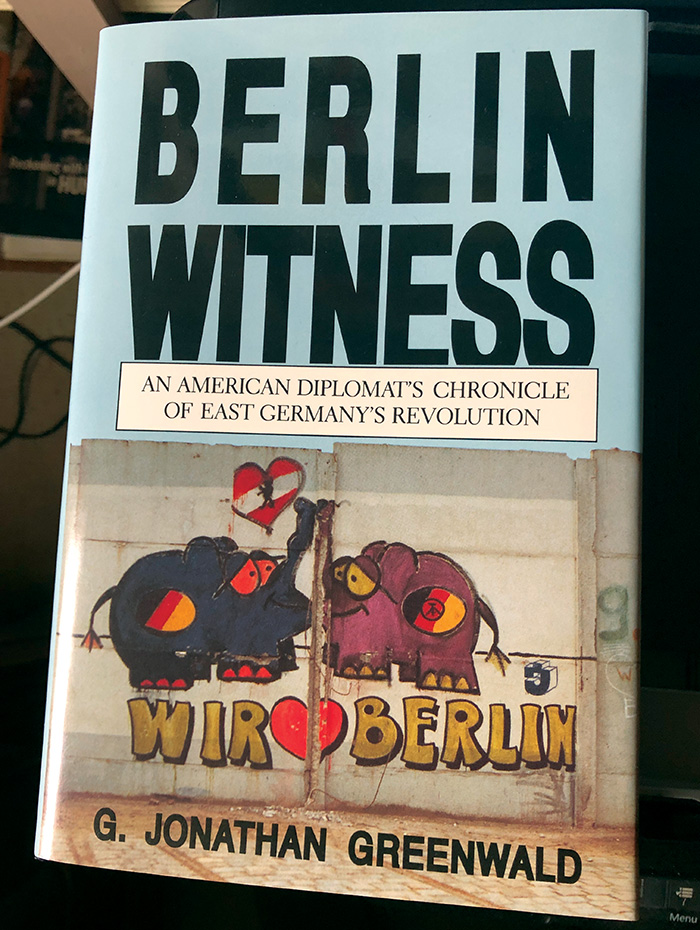

Jon Greenwald’s book, originally published in 1993.

Jon Greenwald

To Celebrate or Sleep?

Jon Greenwald

East Berlin, German Democratic Republic

As the embassy’s political counselor in East Berlin, I spent hours that evening telling colleagues in West Berlin and State’s Operations Center not to expect immediate drama. We had been working hard for months as peaceful revolution developed in the German Democratic Republic.

A few days before, a million people had demonstrated in the heart of the city for radical changes. All week we were reporting on the Communist Party plenum that revised the Politburo and introduced a reform prime minister. We were anticipating a law to permit extensive travel for East Germans for the first time since the Berlin Wall was built. As I coordinated reporting, I watched the televised press conference; the party’s spokesman, Guenter Schabowski, ended with a comment on new regulations that would allow applications for immediate travel.

My phone began to ring. Ambassador Dick Barkley had heard Schabowski and wanted us to inform Washington. Then the head of the U.S. mission in West Berlin [known as USBER], Harry Gilmore, called to say that the mayor had told him plans were ready, since Schabowski had advised him a week earlier to expect visitors soon.

“When will it begin?” Harry asked.

Schabowski said documents would be needed, I explained, though police offices would probably be swamped by applicants the next morning.

Imre Lipping, my deputy, arrived to compare notes. We agreed there were unanswered questions. There could be a long wait for passports, if only because millions would have to be issued. But if the authorities processed applications as promised, the question would arise what purpose the wall retained. Unless the GDR acknowledged it was becoming an anachronism, many would conclude liberalization was only a gambit that could be withdrawn as quickly as it was introduced.

When my wife, Gaby, a Berliner, arrived home, she recounted a troubling experience minutes earlier while returning from visiting her mother in West Berlin. As she left the checkpoint, a dozen men blocked the street. She first thought they were drunk but saw no bottles, and more people came out of apartment buildings, apparently to join them. I knew nerves were stretched tight and hoped the restraint that had carried East Germans so far would not fray just as their demands appeared close to realization.

Our embassy was empty except for communication officers Duane Bredeck and Larry Stafford when I handed in my cables and began to drive home to the Pankow district. Downtown was empty, though lights were burning at party headquarters. But at Schoenhauser Allee, in the shadow of the elevated train, thousands were streaming through the Bornholmer Strasse intersection. Police were struggling to keep a lane to Pankow open, but the crowd was intent on reaching the wall.

I was frightened for them and the peaceful process we had witnessed all fall. There were troops just a few hundred yards away. If Berliners did not wait for morning and demanded to be allowed through now, how would the young soldiers in the watchtowers react? Was there one panicky youth with a gun on either side of the barrier? Warnings that a violent incident could bring civil war were on my mind.

I considered joining the push toward the wall, but in that age without cell phones, it might be hours before I could reestablish outside contact. Better to continue home to put out my alert. Unusually, lights were on in many houses on our street. Ours, however, was dark. I woke Gaby, who stood anxiously beside me as I telephoned J.D. Bindenagel, the deputy chief of mission. Thousands are pushing toward the wall, I told him, and there may be trouble.

“It’s all over,” he replied. “They’ve opened the wall. I’ve spoken with Washington. Turn on your television.”

And so we saw the joyful scenes. Gaby, a student when the wall went up, had known it all her adult life. “I don’t believe it. I just don’t believe it,” she said, before asking, “Should I dress? Should we go downtown?” I wanted to, but it had been a long day, with a longer one starting in a few short hours.

So we went to sleep while Berlin celebrated, though we cried a bit first. And then our embassy began to report on the new Germany that was being born.

Jon Greenwald is a 30-year veteran of the U.S. Foreign Service. Since 2017 he has been working on a project to bring young Israeli and Palestinian students to study together for a three-year period at leading prep schools in the United States, Germany and Israel.

Managing from Moscow

Raymond F. Smith

Moscow, USSR

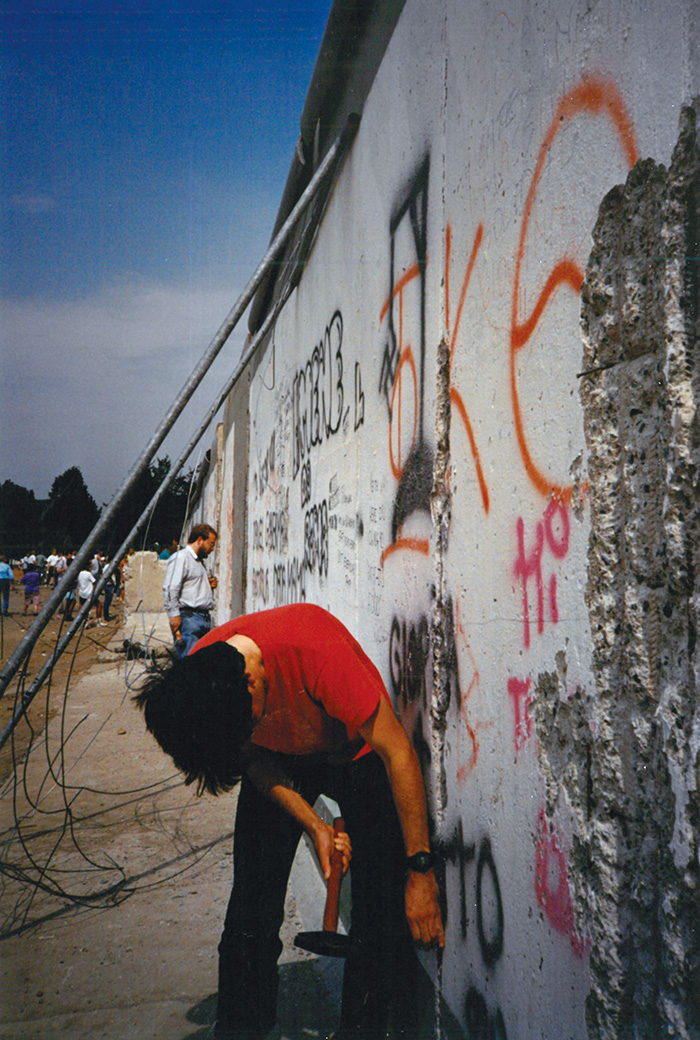

An American visitor chips away at the wall in an open Berlin, spring 1990.

Shawn Dorman

World-shaking events do not always occur on personally convenient timetables. If they had asked me, I’d have told the East Germans to pick a different week to tear down that damned wall.

It greatly inconvenienced me. You see, I was unofficially in charge of the U.S. embassy in Moscow at the time. I say unofficially because the ambassador was in the country, although on a visit to one of the Soviet Union’s far-flung republics. With the deputy chief of mission out of the country, I was filling in for both. But that was not the real inconvenience.

Rather, my wife was out of the country, our nanny was not in Moscow and I was working out of the DCM’s office with my 10-week-old son strapped to my chest in a baby pouch. My plans for the weekend included heating the reserve supply of breast milk to the proper temperature, changing diapers and, probably, getting precious little sleep. Not the best setup for trying to get information from the Foreign Ministry about Soviet views on the rapidly unfolding developments.

Of course, we were not going to get any immediate information out of the Foreign Ministry in any case, because on something like this no one would comment before Communist Party General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev or Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze did. There are times, though, when as a diplomat you know what a country is going to do. You know it because you have been there for a while, and you have what I can only call a “feel” for things—a combination of facts, firsthand observations and intuition that is almost unattainable from a distance. It is a resource that is, unfortunately, often undervalued at the political level.

Many of Gorbachev’s foreign travels during the prior year had been to Eastern Europe, where he told the Communist Party leaderships that they needed to reform, that if their people rose up against them, the Red Army would no longer intervene on their behalf. He meant it. The “new thinking” that he and Shevardnadze had made the cornerstone of Soviet foreign policy had as a principal tenet an end to what he called the enemy image of the West.

This was not just a slogan. It was essential to Gorbachev’s domestic reform effort, the basis for major cuts in Soviet defense spending that would free resources for domestic needs, improve peoples’ lives and solidify support. None of that worked out in the long run, but there remained a lot of optimism for it in 1989. Intervention would have meant the end of the reform effort; he would not allow it as long as he remained in power.

On the Monday after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the vast majority of East Germans who had crossed returned home to work. The Soviet leadership breathed a sigh of relief. Russians fear chaos, but the only explosions they had seen were of joy. The end of the wall was a fait accompli, the disintegration of the East German regime a probability. In the coming months, Gorbachev and Shevardnadze would seek to turn this situation to their advantage by trying to negotiate an end to their no-longer-tenable position in Germany in return for aid and Western acceptance.

The seeds of our current problems with Russia were planted in those negotiations, but that is a matter for a different discussion.

Raymond F. Smith, who was in Moscow when the Berlin Wall fell, was a Foreign Service officer from 1969 to 1993. A longtime international negotiations consultant, he is the author of Negotiating with the Soviets (1989) and The Craft of Political Analysis for Diplomats (2011).

Predicting the Fall

George F. Ward Jr.

Bonn, Federal Republic of Germany

When East Germans began streaming to the West through the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989, I was deputy chief of mission at the embassy in Bonn. The events of that day set in motion a swift process that led to the unification of Germany on Oct. 3, 1990.

The fall of the wall came as no surprise to Ambassador Vernon A. “Dick” Walters. On April 7, 1989, while preparing for his assignment to Germany, Walters had asked me to be his deputy. At the beginning of our conversation, he said, “George, we’re going to Germany at a very interesting time. The Berlin Wall’s going to come down.”

At the time, this was an astounding statement, and I was skeptical. The conventional wisdom ascribed to by some of the State Department’s Germany experts and by a number of West German political leaders was that German unification would take place only over an extended period of time, through a convergence of the systems in East and West. Walters had a broader vision and a different view. The Soviet Union had suffered a defeat in Afghanistan and was weakened economically. General Secretary Gorbachev, Walters reasoned, would not use the Red Army to quell the popular unrest that was bubbling just below the surface in East Germany. Therefore, German unity seemed plausible, even predictable.

The geopolitics of German unity were worked out through the Two Plus Four negotiating process, which involved the four World War II Allies—the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union—plus the two German states. The embassy in Bonn supported this process but found its principal role in helping to wind down the special status of the four powers in Germany.

The sovereign status of the four powers was most evident in Berlin, but it also provided the basis for many institutions and activities throughout Germany, including the stationing of NATO forces and even the right of the United States to occupy the embassy complex in Bonn. Along with many other members of the embassy and mission in West Berlin, I was involved in quite a number of formal and informal negotiating processes. All of this unfolded at a dizzying pace, and the outcome was unclear until close to the end.

For me personally, German unification brought the joy of family unification. My grandmother had emigrated from Saxony to New York early in the 20th century.

–George F. Ward Jr.

The most consequential negotiation concerned the future status of the more than 200,000 U.S. military personnel and tens of thousands of other NATO troops in a unified Germany. For a while, some negotiators on the West German team maintained that members of NATO forces would be restricted from entering the territory of the former East Germany, perhaps even on personal travel. Although the Allies had no intention of establishing bases in the former East Germany, the proposed travel restrictions were unacceptable.

In addition, German proposals to subject Allied military personnel and their families to German law in a number of mundane areas would have posed substantial inconvenience. It is a tribute to the excellent German-American relationship that had been built up during the years since World War II that these and other questions were resolved through frank but amicable dialogue in time for German unification.

Embassy Bonn’s role in the German unification saga was best summed up by words included in the group honor award it received: “a classic example of successful American diplomacy, in which intelligence, energy, dedication and a clear understanding of U.S. interests combined to produce results beyond expectations.”

For me personally, German unification brought the joy of family unification. My grandmother had emigrated from Saxony to New York early in the 20th century. When the Berlin Wall came down, I was able to establish contact with relatives in the East. Visiting with them in their workers’ apartment in Halle brought both joy and sadness—joy over discovering family I had never known, but sadness about the grim conditions they had endured since 1945.

Later, I was able to bring my relatives to Bonn for a tearful, cheerful time with my mother, who was visiting us. Our happy walks along the Rhine made me thankful for the work and sacrifices of so many that resulted in a good end to the Cold War.

The deputy chief of mission in Bonn in 1989, Ambassador George F. Ward Jr. was a Foreign Service officer from 1969 to 1999. Since retiring, he has served in leadership roles at the United States Institute of Peace, World Vision and the Institute for Defense Analyses.

How I Became a Mauerspechte

Edwina “Eddie” Sagitto

Heidelberg, Federal Republic of Germany

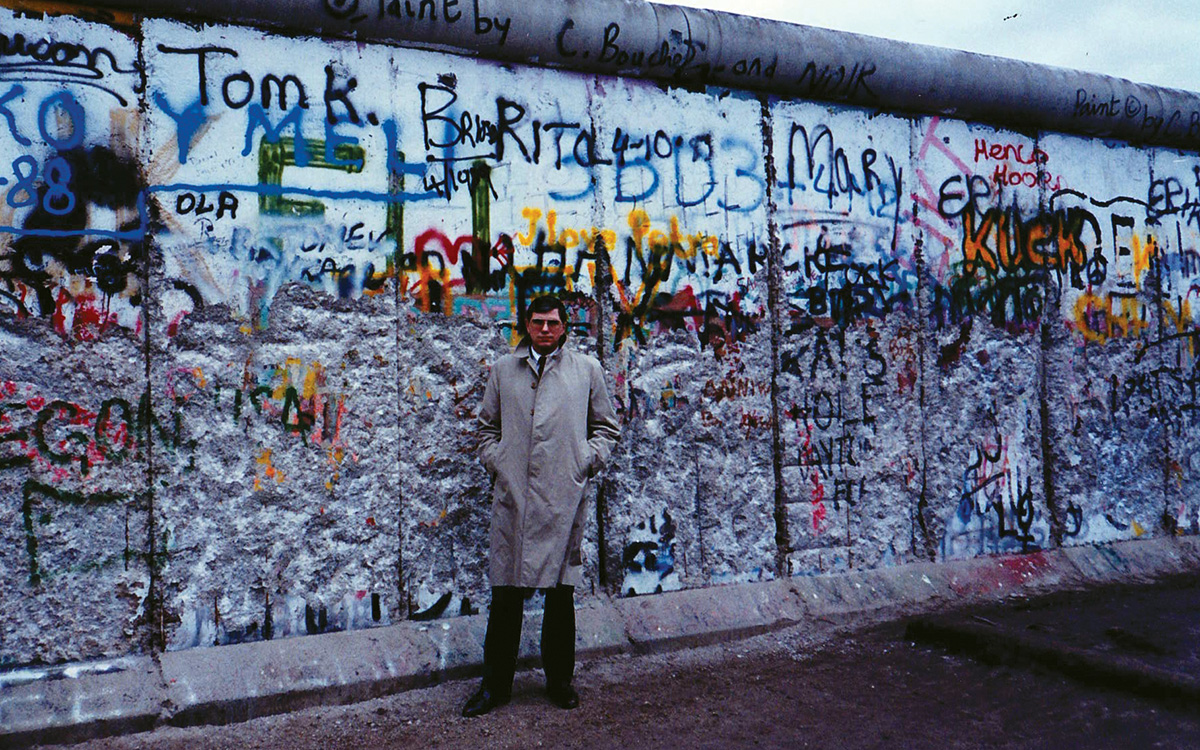

Eddie Sagitto at the Berlin Wall.

Courtesy of Eddie Sagitto

In November 1989 I was living in Heidelberg, working as a management analyst for U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR). On Nov. 9, while visiting the German family of my partner in the Bavarian city of Neu Ulm, we heard the news that the Berlin Wall had fallen. I was ecstatic, but my German hosts didn’t seem impressed.

I wanted to experience the change firsthand, so the following weekend I went to Berlin. The mood was euphoric, but the huge crowds were gone. It was easy to access the Berlin Wall and soak in the atmosphere. There was a lively trade going on in pieces of the wall chipped off by enterprising kids known as mauerspechte, a slang word meaning “wall peckers.” Some were spray-painting parts of the wall before breaking off pieces to make them more saleable. I decided to chop off my own. It was not too difficult because the wall was made of porous concrete, and I amassed a whole bag full of chunks.

Things seemed to change quickly in the weeks and months that followed. Less than a year later, on Oct. 3, 1990, West and East Germany reunited. Some of the early enthusiasm in the west diminished as the costs of reunification became clearer. The U.S. military presence also changed, as the number of U.S. military personnel stationed in Germany (and the German and U.S. civilians working with them) dropped drastically.

For me, the fall of the Berlin Wall also opened up the possibility of travel to Eastern Europe. In 1991, after quite a bit of preparation, I went to Romania in hope of adopting a child. I traveled with a colleague and friend who also wanted to adopt. With the help of a translator and advice from others who had successfully adopted, we were both able to adopt, I a daughter and she a son.

In 1995 I joined the Foreign Service and had assignments in Slovakia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Romania. The events of November 1989 not only had a profound effect on Germany and Europe, but on the direction my own career and life have taken.

Edwina “Eddie” Sagitto joined the Foreign Service in 1995, serving until 2013 as a public diplomacy officer. Since retiring, she has taken WAE assignments in Africa and elsewhere, and divides her time between Munich, Germany, and Phoenix, Arizona.

View from the Velvet Revolution

Thomas N. Hull

Prague, Czechoslovakia

Two young mauerspechte sell pieces of the wall.

Courtesy of Eddie Sagitto

An enterprising individual spray-paints part of the wall for later sale.

Courtesy of Eddie Sagitto

When I left Washington in August 1989 to be a public affairs officer in Prague, conventional wisdom was that communism would collapse in Czechoslovakia before East Germany. Ambassador Shirley Temple Black arrived a week later, fully prepared to maintain our strategy of encouraging dissidents, promoting human rights and opposing communism, as had generations of American diplomats before us.

Within a month, a seismic upheaval began when East German refugees crossed the open border with Czechoslovakia in growing numbers to claim asylum at the West German embassy neighboring our embassy. Disoriented refugees scaled the U.S. embassy’s security wall and were redirected over the adjacent German wall. The West German embassy overflowed, forcing thousands of asylum seekers to live on the cobblestone street in front of our embassy for weeks. The crisis focused world attention on Prague until October, when trains took the refugees to West Germany via East Germany. Berliners then increased pressure to eliminate travel restrictions to the West, which culminated in the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9.

In Prague the Czechs were slower to react. Although the resolution of the refugee crisis showed that Mikhail Gorbachev would not oppose freedom, the Prague populace, remembering how the Soviets violently crushed the 1968 Prague Spring, remained uncertain. A police assault on a Nov. 17 student demonstration finally sparked a mass reaction. Dissidents and intellectuals, most of whom were close embassy contacts, formed the Civic Forum to lead the Velvet Revolution.

After demonstrations of up to 500,000 protesters spread, the communist leadership resigned on Nov. 24. By the end of December, dissident dramatist Vaclav Havel was president, and deposed Prague Spring leader Alexander Dubcek was resurrected as president of the National Assembly.

The atmosphere changed immediately. The secret police removed their hidden cameras and listening devices from my apartment. Soon thereafter, I found myself on stage congratulating Czechoslovakia for its revolution in front of President Havel and 20,000 fans at a nationally televised concert.

Our strategy quickly shifted to nurturing democracy and transforming the Czechoslovak economy. Our activities were limited only by sparse budgets and our minimal American staff, who worked 14-hour days, sometimes longer, seven days a week for months on end. Although resources eventually increased in all embassy sections, workloads also grew exponentially.

Czechoslovakia immediately became a magnet for visitors. Ten senators and 56 representatives came in the first two months. Some had real public diplomacy value, such as House Majority Leader Richard Gephardt, who spoke on democracy to Charles University law students. Secretary of State James Baker and Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy also addressed students.

We shamelessly recruited private visitors as well. Most memorably I arranged directly for rival media moguls Katharine Graham and Rupert Murdoch to dine together with Ambassador Black and me for a discussion with prominent Czechoslovak women on their role in the new democracy.

The ultimate visitor was President George H.W. Bush, who announced to 200,000 people in Wenceslas Square that the Lenin Museum would become the American Cultural and Commercial Center. The Czechs understood the significance—this was the building where Lenin established the Bolshevik party in 1912, setting a course that culminated in the Cold War.

Another consequence that commanded our attention was the rise of Slovak nationalism. The American consulate in Bratislava reopened. At the ribbon-cutting we reunited Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Claiborne Pell, who had been our last consul general in Slovakia, with his Foreign Service National assistant, Lubomir Elsner, who had disappeared in 1952 and spent 11 years as a political prisoner.

As our resources grew, we brought legal experts to Bratislava, including California Assistant Attorney General Adam Schiff, now chair of the House Select Committee on Intelligence, to advise Slovak leaders. Despite our best efforts, Slovak nationalism eventually produced a velvet divorce between the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

These recollections merely give the flavor of our diplomatic activities and accomplishments in response to communism’s demise. The Foreign Service performed magnificently with extraordinary dedication throughout the Velvet Revolution. This was recognized by Ambassador Black, who presented us each with a pewter mug engraved to “Team ’89 Veterans” as a memento of her appreciation when she departed post in 1992.

Ambassador Thomas N. Hull was a public affairs officer in Prague in 1989. In retirement he has been Warburg Professor of International Relations at Simmons University in Boston and president of Foreign Affairs Retirees of New England. He lives in Grantham, New Hampshire.

What Would Austria Do?

Robert F. Cekuta

Vienna, Austria

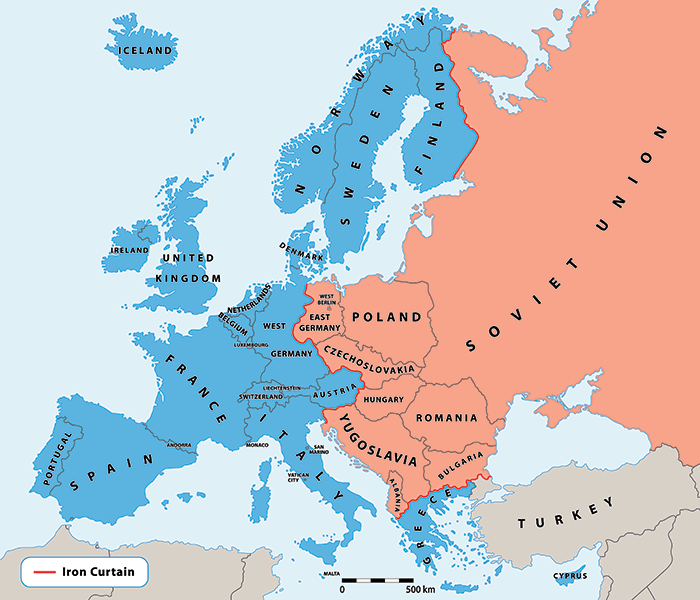

Cold War Europe.

Peteri / Shutterstock.com

The U.S. embassy in Vienna in 1989 was a key post for monitoring the changes that were underway in the Warsaw Pact. In the economic section where I worked, prime concerns included East-West trade—i.e., the levels, the composition and the actors in trade and investment between the West and communist countries—as well as the control of exports of Western dual-use and other sensitive goods and technologies.

We frequently met with Austrian bankers and others doing business in the East for their view of the economic situations in those countries, as well as to get insights into the reform processes and how the West might support an economic and political transformation. Austria’s media, building on traditional ties and the country’s post-1955 neutrality, were useful sources; Austrian journalists in Prague, Budapest, Berlin, Moscow and elsewhere reported daily in detail on the political dynamics and democratic aspirations in each capital. We also monitored the public’s hope and confusion over how events in the East were unfolding.

The relative relaxation of Hungary’s border controls had brought influxes of Hungarians and, later, East Germans into Austria. East Germans tended to drive through to West Germany, while Hungarians and others came for weekend shopping along Vienna’s Mariahilfer Strasse, buying appliances, housewares and other Western goods that were in short supply at home. The Austrians welcomed the Eastern Europeans, seeing their visits as positive signs of a relaxation of communist totalitarian controls and of a possible return to a prewar Central Europe.

It was a shock that Friday night when we found out the Berlin Wall had fallen, and questions about what it all meant followed. My wife and I heard the news from a German friend whose brother lived in West Berlin. Though unclear about what exactly was going on, his excitement matched the mood in Vienna that weekend. Younger Austrians were euphoric. Viennese of all ages lit candles and said prayers of thanksgiving in the city’s numerous churches. The end had come peacefully, bringing hope for the people in the communist East and a sense that this opening in Berlin would assure them all a better future.

The opening of the wall and the sudden ability of East Berliners to travel to the West was a strong sign for the public that Mitteleuropa, the Central Europe that Austrians looked on as a lost cultural and economic entity, could now become a reality again. Certainly many Austrian bankers and business people saw great potential for investment and economic expansion.

However, at the same time, memories of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 led to caution and concern that the Soviets might again clamp down hard. Also, in early November 1989, there was no certainty that Prague, Sofia, Bucharest or Tirana would tolerate democratic reforms. In Vienna, initial jubilation evolved into a cautious optimism tempered by years of dealing with the Soviets and the region’s other communist states.

As the permanence of the opening and changes in the East became apparent, the number of American businesspeople coming through Vienna grew markedly, and Austria’s government and business community sought to remake Vienna as the center for economic activity in the Danube Basin. With the understanding in the East that democracy and prosperity were connected, conferences and delegations focused on what was necessary to establish free-market economies with enterprises that could compete regionally and globally.

Questions about the reunification of Germany and its implications for Austria also arose, including what it might mean for the European community if Austria joined, as it hoped to and indeed soon would. Other European governments even raised what now seems an outlandish concern: that Austria might unify with Germany.

My tour in Vienna ended in 1992. The political, economic and social changes were well underway and becoming institutionalized, notwithstanding the growing trepidation within Austria about refugees and illegal immigrants coming from the East. The overall sense was of gratitude that the wall was gone; now our work had to be realizing the opportunities for the new Europe.

An economic officer in Vienna in 1989, Robert F. Cekuta retired from the U.S. Foreign Service in 2018 after serving as U.S. ambassador to Azerbaijan. He now divides his time between Washington, D.C., and Jefferson, Maine.

A Study in Change

Margaret K. McMillion

Washington, D.C.

In 1989, I was a member of the Class of 1990 at the National War College. We began the year firmly set in the Cold War. Our first reading assignment, John Lewis Gaddis’ Strategies of Containment, set the stage for the next 10 months.

Change, though, was in the air. In the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev was promoting glasnost and perestroika. Vietnam and Laos had initiated market reforms known as New Thinking and the New Economic Mechanism (Doi Moi and Chintanakhan Mai). Yet events at Tiananmen Square that June had shown the limits of reform in China.

Throughout the fall of 1989, our class watched with wonder as the pace of change accelerated in Eastern Europe. A Solidarity-led government took power in Poland in late August. Hungary and Czechoslovakia allowed “holidaying” East Germans to travel on to Austria and take refuge in West Germany. The East German government agreed that citizens seeking asylum in Budapest could go by train to West Germany. Following protests in Leipzig, General Secretary Erich Honecker resigned. On Nov. 9, the East German spokesman announced (inaccurately, we later learned) that citizens could leave by any border crossing. Guards opened the checkpoints between East and West Berlin, and the Berlin Wall was gone.

The challenges are many, but the opportunities have never been greater.

–National War College Class of 1990 Yearbook

More was to come, and the evening news brought new developments every day: in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and, ultimately, Romania, democratic governments assumed power. For me, one of the most memorable events was the invasion of the East German Stasi offices in Erfurt in January 1990. An incredulous CBS correspondent stood amid flying paper and demonstrators who were determined to stop the remaining officials from destroying their files, which today are declassified. Among the military officers in the class, there was a palpable sense of relief that they were unlikely ever to fight a war in Europe.

These events had an immediate impact on our academic program as we began to discuss a possible “peace dividend” and “new architecture” in Europe. Faculty member Stephen Szabo told USA Today that students faced a situation comparable to the fast-moving events at the end of World War II. His suddenly popular area studies class on Eastern Europe and the Warsaw Pact, which I took in preparation for a spring field trip to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Austria, focused more on political and economic reform than military doctrine. By the time the course concluded in April, the Warsaw Pact was becoming a relic of the Cold War. It would later be dissolved.

The yearbook staff decided that change was the only possible theme. The winds of change were also blowing elsewhere, especially in South Africa where Nelson Mandela walked free in February and Namibia became independent in March. We wrote in the foreword: “The challenges are many, but the opportunities have never been greater.” Two pages provided a chronology of a memorable 10 months in world affairs.

It was an exciting time, disorienting in many ways, but filled with hope about the possibilities for building a more peaceful and prosperous world.

Margaret K. McMillion was U.S. ambassador to Rwanda from 2001 to 2004. In 1989 she was studying at the National War College in Washington, D.C. Ambassador McMillion currently resides in Bangkok.

Graffiti on the longest-remaining section of the Berlin Wall, featured at the open-air East Side Gallery, Berlin, 2015.

James Talalay

In the Airport with Walesa

John J. Boris

Warsaw, Poland

The Berlin Wall had just fallen, and Lech Walesa was heading to the United States.

Those of us serving in Warsaw, Krakow and Poznan in 1989 had front-row seats as Solidarity, the free trade union, through negotiations, activism and elections, outmaneuvered the Polish United Workers’ Party (i.e., the communists) into the step-by-step surrender of its power. As the deputy to the political counselor at Embassy Warsaw since July 1988, I had lucked into the exceptionally interesting role of maintaining working-level contact with the trade union, a job that brought regular interaction with some of Solidarity’s most eminent figures, such as Adam Michnik, Bogdan Lys and, at times, even Chairman Walesa himself.

When President George H.W. Bush visited Poland in July 1989, I was the site officer for the home-cooked lunch at which Lech and his wife, Danuta, hosted the president and first lady. By the time I escorted the fourth congressional delegation—a total of 21 members over the course of 18 days in August 1989—to Gdansk, the union leader and I were simply nodding at each other in greeting. That presidential visit, and the wave of visiting legislators, led to invitations for Walesa to visit the White House and address a joint session of Congress. Walesa and his party were planning to fly out of Warsaw on Friday, Nov. 10, and several of us from the embassy planned to use that Veterans Day holiday to see them off.

I was washing my breakfast dishes that morning as the BBC World Service reported that, late the previous evening, the East German authorities had lifted border controls. The Berlin Wall had fallen. I teared up. Poland had seen a succession of evermore remarkable “Is this really happening?” developments over the course of the year, but even by those standards, this news was breathtaking.

That is certainly how the Solidarity delegation in Warsaw’s Okecie airport departure lounge viewed things. “Nie do wiary!” (Unbelievable!) averred Krzysztof Pusz, Walesa’s aide-de-camp and one of my closest contacts, as we exultantly greeted each other. Ambassador John Davis and his spouse, Helen Davis—a savvy diplomatic presence in her own right—were engaged in conversation with a beaming Walesa. I could not hear what they were saying, but it was not hard to read the trade union leader’s mood. Indeed, all of us in the departure lounge were quietly or giddily incredulous. Walesa’s upcoming Nov. 15 address to a joint session of Congress had just taken on even greater significance.

In 1989, before Poland’s market reforms had kicked in, it was common for Embassy Warsaw personnel to make several shopping runs a year to U.S. military facilities in West Berlin. By a happy coincidence of timing, my wife and I had scheduled one beginning on Nov. 13. Within days of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Anne and I were outside the KaDeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens, a department store), gaping at the Trabants full of people gaping back at us.

John J. Boris joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1980. He was the deputy political counselor in Warsaw when the Berlin Wall fell. Mr. Boris lives in Annandale, Virginia.

Europe Changed, But Africa Didn’t

Mark G. Wentling

Lomé, Togo

Lomé, on the west coast of Africa, is a long way from Berlin. Yet when the Berlin Wall came down in November 1989, the repercussions were felt in Togo and other countries in Africa, where people were struggling to overthrow dictators and establish multiparty democracy. We all thought the fall of the wall marked the end of the Cold War, and we believed that a huge peace dividend was just around the corner.

I was USAID’s representative for Togo and Benin, based in Lomé, at the time. Violent protests against the dictatorial regime in power for 22 years were frequent. The people had had enough of an authoritarian one-party system and wanted a democracy that reflected their hopes for a better future. The dismantling of the Berlin Wall raised their hopes of achieving lasting democratic change; it strengthened their case and the justness of their cause.

We thought the end of Cold War politics would mean an end to the superpower alliances in Africa, where superpowers would vie for client countries in the region, often propping up bloody and corrupt national regimes. For example, U.S. foreign aid was often lavished on those African countries that were staunch opponents of communism, despite the despicable acts of their autocratic rulers.

We believed that in a post–Cold War era, the United States could determine its level of assistance to African countries without applying international political considerations. It could also decide more clearly what its strategic interests in each country were beyond providing humanitarian assistance.

The fall of the wall thus gave renewed hope to Togo and other African countries. Sadly, in Togo’s case, these hopes were shattered, and the promise never realized. Togo’s dictator, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, who stayed in power for another 16 years until his natural death in 2005, was replaced by his son. The legacy of Gnassingbé Eyadéma proved far more powerful for Togo than the collapse of the wall.

In hindsight, the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years ago has had little, if any, consequence for Africa—or for my lifelong pursuit for the betterment of this vast continent. There are still many critical “walls” of injustice and poverty to break down in Africa.

Retired FSO Mark G. Wentling joined USAID in 1977 and was serving in Togo when the Berlin Wall fell. His work and travels over the past 46 years have taken him to all 54 African countries.

It Couldn’t Possibly Happen Here

Kay Kuhlman and Brian Flora

Bucharest, Romania

In November 1989 we were serving in Bucharest. Brian was head of the political section, and Kay was the commercial officer. The Romanian government suppressed all news of the Berlin Wall’s demise, but we in the embassy were aware of Eastern European developments from cable reporting and Voice of America broadcasts.

And we were envious. The region was opening up, and there we were in a country seemingly stuck tight under the thumb of despot Nicolae Ceausescu and his Securitate goons. Even next-door Bulgaria, in those early days of November, joined the revolutionary movement and ousted Communist Party leader Todor Zhivkov.

Brian believed that street demonstrations would not be enough to overthrow the Ceausescu regime because the dictator would not hesitate to use deadly violence against his own people. Kay remembers telling some U.S. government visitor to Bucharest that, regrettably, it didn’t look like Romania would follow its Eastern European neighbors anytime soon.

Brian had limited contact with political dissidents in the capital (it was technically illegal for them to talk to us without written permission from the Securitate), but most of the mid-December opposition activity in Romania was centered in Timisoara and other locales distant from Bucharest.

We did not anticipate that just six weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Romania would follow suit, going down in the record books as the only country in Eastern Europe whose people freed themselves through a shooting war in the streets. (Our experiences during those scary, but ultimately heady, December days is a story for another time.)

Retired FSOs Kay Kuhlman (Foreign Commercial Service) and Brian Flora (State) live in Oak Park, Illinois.

“That Is the End”

John W. “Jack” Bligh Jr.

Koenigswinter, Federal Republic of Germany

My wife and I were watching West German TV at our home in Koenigswinter, across the Rhine from the embassy, when the images of East Germans coming through the wall were shown. Was I surprised? Most certainly, especially by the spontaneity and lack of bloodshed.

In the following days, my job brought me into contact with a number of West German business leaders, several of whom said that they had never expected to see in their lifetimes any freedom of movement through the barrier. I like to think that I saw a tear or two in the eyes of some.

For a time after the opening, one might see an East German Trabant car abandoned beside the autobahn, probably because the fuel mix it required was not available in the Federal Republic. The magnitude of their owners’ joy at their newfound freedom is even clearer when one considers that they had waited for up to 17 years to buy a car.

The impact on my work was not overnight, but we would soon add constituent-post commercial operations in Berlin and Leipzig, and a lot of our commercial section and country team efforts went into ensuring that American companies would have a fair shot at the privatization of state-owned companies in the East.

Not many saw the days leading up to Nov. 9 as the beginning of the end of the German Democratic Republic, but at least one did. On a Monday in October 1989, before the wall fell, I had accompanied Ambassador Vernon Walters to West Berlin. (Mondays were the days of the Wir sind das Volk—We Are the People—demonstrations in East German cities, especially in Leipzig.) The ambassador, our minister in West Berlin, Harry Gilmore, and I were guests at a dinner hosted by West Berlin Mayor Walter Momper.

During that dinner, an aide came in and whispered something to Mayor Momper, who arose and announced that the East German military, which had been prepared for confrontation, had not fired on or interfered with the demonstration in Leipzig. I was seated next to Momper’s predecessor, Eberhard Diepgen, who said: “That is the end of the GDR.”

John W. “Jack” Bligh Jr. was a Foreign Service officer from 1966 through 1996. He was serving as the Minister Counselor for commercial affairs in Bonn when the Berlin Wall came down. He lives in Manlius, New York.

FSO Greg Suchan (above) and his wife, Susanne (below), at the Berlin Wall in December 1989.

Courtesy of Greg Suchan

Courtesy of Greg Suchan

My Piece of the Wall

Greg Suchan

The Berlin Wall

In the autumn of 1989, I had just finished two years as the pol-mil officer in Islamabad and was scheduled to begin Danish language training before setting off to Copenhagen as political counselor.

As a bridge assignment, I was sent to the NATO Defense College in Rome for six months. The course included a trip to Europe, including a stop in Berlin that happened to coincide with the fall of the wall. Swept up in the drama, my wife and I went directly to the scene of the action. We watched a German man whack away at the despised wall with a hammer and chisel.

When we identified ourselves as American diplomats, he handed over two pieces. I offered to pay him, but he wouldn’t take a pfennig. Those pieces of the Berlin Wall, mementos of a world-changing event, formed a bridge between two chapters of our diplomatic life characterized by equally historic developments.

In Pakistan, we had been witnesses to the Red Army’s final collapse and withdrawal from Afghanistan. In Copenhagen, we participated in the first outreach to the new Baltic republics that had opened interest offices in the Danish capital, playing a small role in the construction of the post–Cold War political and security architecture in Europe.

Greg Suchan was a Foreign Service officer from 1973 to 2007. He currently runs International Consulting LLC. He and his family live in Flat Rock, North Carolina.

After the Fall: Labor Unions in Europe

Dan E. Turnquist

Brussels, Belgium

A Berliner attacking the wall with a hammer and chisel.

Courtesy of Greg Suchan

I was in Brussels serving as the labor counselor in what is now the European Union. I covered the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, which included most of the major unions in the non-communist world. Polish Solidarnosc also had its overseas office in Brussels. And I followed the World Federation of Trade Unions, controlled by the Soviets and headquartered in Prague, which also included communist-controlled unions in the West.

Sitting at home watching the television news Nov. 9, I saw the daughter of a close friend dancing on top of the Berlin Wall as it came tumbling down. My friend had been very active in the fight against communism and had warned his daughter to be very careful in Berlin.

We were all flabbergasted. None of us had anticipated that this would happen so quickly and completely. We had all sensed that the Eastern bloc was in trouble, but we were still surprised when it happened.

The Cold War was a very hot war among the trade unions, with the Soviets pouring money into communist unions while the Social Democratic and Christian Democratic unions, including the AFL-CIO and its affiliates, fought back. This situation—which had existed for 40 years since the communists walked out of a Socialist Congress in Amsterdam, leaving it to the Social Democrats—suddenly collapsed after the fall of the wall.

My job changed radically after that. People who wouldn’t give me the time of day before were now lined up at the mission, wondering if we Americans could help them now that their KGB paychecks were in jeopardy. The head of the Solidarnosc office, who was belittled because he was not one of the well-known principal leaders of Solidarnosc in Poland and whose offices were regularly ransacked by the KGB and Polish intelligence, suddenly became the head of Poland’s National Security Council. The world was being reordered.

With the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, we had to help Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States set up employment offices, unemployment insurance systems and all the other trappings of capitalist, market economies. We had a whole series of meetings in Brussels as the Western countries tried to determine how to proceed in a coordinated fashion to cope with this new world.

Playing a role in all of this was the most interesting and meaningful assignment in my 35 years in the U.S. Foreign Service. I worked long hours but had the satisfaction of knowing I was involved in earthshaking events.

Dan E. Turnquist served in the Foreign Service from 1966 to 2001. He retired as a Minister Counselor and currently splits the year between Centennial, Wyoming, and Guadalajara, Mexico.

The view into East Berlin from Checkpoint Charlie in January 1990.

Courtesy of Susan Stevenson

Susan Stevenson near a section of the Berlin Wall in January 1990.

Courtesy of Susan Stevenson

A Good Time for a Visit

Susan N. Stevenson

East Berlin, German Democratic Republic

In November 1989, I was in my second year of work in the private sector and busy planning an international trip. American, French and Scottish friends would join my sister and me on a road trip through what was then Czechoslovakia and East Germany in January 1990.

I remember quite well when the Berlin Wall fell on Nov. 9. We saw the images of hundreds of people crossing from the East into West Berlin, as well as the crowds along the wall. We also heard reports of the Velvet Revolution in Prague and the toppling of leaders there and in Romania. For a few days, we wondered about the wisdom of making our trip.

Luckily, we realized the timing was actually fortuitous, as it would give us firsthand experience of a historic moment. We proceeded as planned, driving from Frankfurt to Prague and then to East Berlin. When we arrived at the Brandenburg Gate in January 1990, we were amazed to find young people sitting on top of the wall, busily hammering away at it. The soundtrack of that trip was the metallic “tap tap tap” of hammers against the concrete to bring down a hated symbol of division and suppression. What mere months before could have gotten them shot—climbing the wall, crossing into the West—was now a joyous moment of community.

I remember sharing a bottle of Russian champagne with two young East Germans on their first-ever trip to West Berlin. They were delighted to meet our international group. They were particularly happy to meet my sister Barbara, who at the time worked for Disney World in Florida, seemingly embodying the American dream. My Foreign Service career was still a few years away, but my interest in international connections was already strong.

We managed to bring back a souvenir: a piece of the wall, which my sister framed.

Susan N. Stevenson was working in the private sector in 1989. She joined the Foreign Service in 1992, and is now serving as ambassador to the Republic of Equatorial Guinea.

The USA Pavilion Goes Forward

Gert Lindenau

Frankfurt, Federal Republic of Germany

In 1989 I was attached to the American consulate general in Frankfurt as director of the U.S. Travel and Tourism Administration for the U.S. Department of Commerce. I was setting up the USA Pavilion at Berlin’s International Tourism Exposition where more than 280 exhibitors from across the United States were expected in March 1990 to meet tour operators and travel agents from all over the world, expanding tourism to their individual destinations and increasing awareness of their services.

When the wall fell in November 1989, it sent shock waves throughout the tourism industry. My office was inundated with questions from potential exhibitors as to what would happen in March. Will all East Germany come? Will I need 100 times the brochures and information to pass out? Will it be safe from terrorists? Will there be enough hotels in Berlin?

Everyone was pleased to see the communist regime implode, and many rightfully expected an increasing number of visitors to the United States in the coming years. For the last day of the exposition, I planned a tour, with the help of buses provided by the U.S. embassy, so U.S. exhibitors could view the remnants of the wall. Participants met the uniformed GDR police officers, who now were very friendly. We saw Checkpoint Charlie and crossed over to East Germany to buy souvenirs (medals, uniform shirts, hats and pieces of the actual wall).

The USA Pavilion was a success even though not many visitors from East Germany were able to attend—they simply didn’t have the Western currency required to participate.

The following years were different for the ITB Berlin, the world’s largest tourism-related fair, and today the United States remains the number one long-haul destination out of German-speaking markets.

Gert Lindenau retired from the Foreign Service in 1993, having served with the U.S. Commerce Department and the U.S. Travel and Tourism Administration. He worked for the Department of Defense in Europe until 2016 and lives with his wife near Kaiserslautern, Germany.

The Berlin Wall as My “Bookend”

John Nix

Nicosia, Cyprus

When the Berlin Wall fell, my wife and I were in the embassy of the Soviet Union in Nicosia, celebrating the USSR’s National Day. At the time, I was chargé d’affaires, and had been for two of the past three years. The Soviet ambassador, with whom I had established quite a close relationship, delivered the news to me.

In fact, the Berlin Wall defined my career. After I graduated from West Point in 1960, my first assignment had been to Berlin as a lieutenant. Not long after my arrival, the wall went up on Aug. 13, 1961. The continuous alerts, the wall patrols, the October 1961 confrontation at Checkpoint Charlie, the many attempts at border crossings by desperate Germans from East Germany—all became iconic pictures I will never forget. Also in the picture: my then-fiancée, now wife of 57 years, who had been born in East Germany and had many relatives there.

After I graduated from West Point in 1960, my first assignment had been to Berlin as a lieutenant. Not long after my arrival, the wall went up.

–John Nix

I had one further assignment to Berlin as an Army officer, from 1969 to 1971, during a somewhat quieter period, when border crossings were more peaceful. After joining the Foreign Service in 1971, we were posted in Moscow and were able to take the Moscow-Berlin train roundtrip twice, after Washington’s diplomatic recognition of East Germany.

At the time the wall fell, I had just learned that my next assignment would be as political adviser (POLAD) to the U.S. mission in Berlin, effectively the deputy chief of mission. We participated in the Two Plus Four negotiations that ensured the withdrawal of Soviet military forces from Eastern Europe, and then the German unification process, followed by many more events that most of us thought we would never see in our lifetimes.

I traveled and reported extensively on the former East Germany, and our efforts were recognized by the State Department’s 1991 Post Reporting Award. In the East we met with, and boosted, future German leaders such as Angela Merkel and Joachim Gauck. Exciting times, indeed.

John Nix served in the U.S. Foreign Service for 25 years, after a career in the U.S. Army. He retired as a Senior Foreign Service officer and lives in Ashburn, Virginia.

Watching from Behind the Iron Curtain

Timothy C. Lawson

Moscow, USSR

An old Soviet TV tower still stands beside a church in what used to be East Berlin. Berlin, 2015.

James Talalay

Late one afternoon I received a call from Ambassador Jack Matlock, who said he needed to see me urgently. As information resources management chief in Moscow, I was frequently called to the executive office.

The ambassador explained that he had just returned from a lunch with the British ambassador, who had casually asked Amb. Matlock if he was impressed with CNN’s reporting. The query left Matlock fumbling for a response. He never watched CNN reporting since it was not available in our embassy—so what was the Brit’s secret? It was my job to find out.

Our embassy had been asking for almost a decade for cable television access like the “Moscow Channel 1” access we had provided to the Soviet embassy complex in Washington via cable. The answer was always a confused nyet.

There was a good reason for the confusion from the Soviets: as it turned out, the Soviet Union did not have a cable TV system like the U.S. did. CNN was actually freely broadcast through Soviet airwaves across the capital. All you needed was a 10-ruble VHF antenna, readily available at the official GUM department store adjacent to Red Square.

Well, we purchased a bunch of those antennas, and our resident telephone/radio technician installed a broadband UHF antenna on the embassy rooftop.

And just in time! As the first chunks of concrete began to crack and crumble from that all-meaningful Berlin Wall—with Gorbachev’s acquiescence—the CNN signal was distributed via our own cable system, allowing all mission employees to watch it on live television.

Timothy C. Lawson is a retired Senior Foreign Service officer who was serving in Moscow in 1989. He lives in Hua Hin, Thailand.

The Wall, Delivered

Judy Chidester

Kigali, Rwanda

When the Berlin Wall came down, I was working as the information management officer in Kigali. It was a quiet town, and except for the announcement of its fall, little was said of the wall. I did have a wonderful experience related to it, though, that is pure Foreign Service.

When our diplomatic couriers came to town, they normally spent their time at my home. A few months after the fall of the wall, one of the couriers brought me a broken piece of it. It still is one of my most treasured mementos, not only because of what it is but because it reminds me of what wonderful friends the couriers were.

Judy Chidester joined the Foreign Service in 1960 as a cryptographer and retired in 1996 as an information management officer. She lives in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

The View from Rostock

Matt Weiller

Rostock, German Democratic Republic

“Honecker has resigned!” These were the first words I heard on arrival at U.S. Embassy East Berlin in mid- October 1989. East Germany’s longtime leader stepping down was a big deal. But even more momentous events were around the corner.

As a German speaker and a Presidential Management Fellow at the U.S. Information Agency, I was chosen to run “American University Bookstore,” the U.S. government’s first (and last) book exhibit in the German Democratic Republic. The exhibit, consisting of more than 500 textbooks and other materials typical of American university bookstores, was held for two-plus weeks each at Humboldt University in East Berlin, Rostock University in the Baltic Sea port of Rostock, and at the University in Magdeburg in Saxony-Anhalt. The postwar order had been teetering since the summer. But the biggest change was just ahead—and I’d have a front-row seat.

The exhibit kicked off at Humboldt with a mix of cautious optimism and state-sponsored surveillance. Our exhibit was assigned a government minder, a certain Frau Beckmann, a fluent speaker of English, Spanish and Amharic (she learned the latter two languages in Sandinista Nicaragua and Mengistu’s Ethiopia). A steady stream of enthusiastic students visited the exhibit, as did no small number of humorless, bulky gentlemen in bad suits—East German State Security (“Stasi”) agents.

One evening, after the exhibit closed for the day, I accompanied an embassy colleague to a demonstration. Police and security personnel outnumbered the protesters by at least two-to-one. A tentative step toward democracy but not one threatening the regime, I wrongly concluded.

The last weekend in October, I walked to the square in front of the Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall) to observe another demonstration. This one was attended by well over 20,000 people, venting about issues large and small. Security forces were present but subdued and greatly outnumbered. It reminded me of an oversized school board meeting—fledgling small “d” democracy in action in a peaceful and slightly messy way. Change was definitely afoot, but to what degree?

While I rued having just missed the opportunity to be in Berlin on Nov. 9, I came to realize that very few Americans could attest to having been “in the field” in East Germany on that day.

–Matt Weiller

The following weekend more than a half million people turned out on both sides of the Berlin Wall to protest the regime. The situation had changed exponentially within two weeks. But I still couldn’t imagine what was about to happen.

On Nov. 7, the book exhibit moved on to Rostock. On the evening of Nov. 9, I was strolling through Central Rostock observing what had become regular weekly protests against the regime. I chuckled as I listened to the protesters chanting “Stasi in die Produktion” (very loosely translated as “Stasi get a real job”). As they passed my hotel, I went back to my room. During that time, I received a call from the embassy cultural affairs officer, Peter Clausson, informing me that the Berlin Wall was now open.

Needless to say, the “American University Bookstore” was overshadowed by these events. As the local populace crowded trains and roadways to West Berlin and Hamburg, the dozen or so students assigned to assist (monitor?) me and my staff of two Americans were our primary contacts. Over endless rounds of coffee and cake, the students and other visitors to the exhibit spoke of their initial impressions of West Germany. Despite having spent their lives watching West German TV, they were uniformly struck by West German modernity and effective public services (particularly the street lighting).

While I rued having just missed the opportunity to be in Berlin on Nov. 9, I came to realize that very few Americans could attest to having been “in the field” in East Germany on that day. After Rostock, the exhibit moved on to Magdeburg. Attendance picked up, while surveillance trailed off. Exhibit visitors opened up to us in a way they hadn’t when we started in East Berlin.

We watched similar rapid change unfold in Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria. While the East German leadership debated how to embrace historic change, there already was a palpable sense that change would overwhelm them in favor of German unification.

Working with the U.S. Information Agency as a Presidential Management Fellow, Matt Weiller was in Rostock, East Germany, when the Berlin Wall fell. He joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1991 and is now deputy executive director for the Bureaus of Near Eastern and South and Central Asian Affairs.

The View from Shirley Temple Black’s Residence

Michael Hornblow

Prague, Czechoslovakia

Ambassador Shirley Temple Black in 1990.

Wikimedia Commons

In November 1989 I was deputy director of the Eastern Europe/Yugoslavia office at State, responsible for Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

My wife, Caroline, and I were visiting the region, which was undergoing rapid change. We had been to Warsaw and Budapest, and it was quiet in the two capitals. Both Poland and Hungary had new democratic governments. The process had been undramatic—nobody had been killed, and there had been no large demonstrations. Czechoslovakia, still under communist control, was a different story. But how long would that continue given developments in neighboring Poland and Hungary? And Prague was filled with thousands of East German refugees seeking a route to West Germany.

Shortly after arriving in Prague either on Nov. 8 or 9, we drove by the West German embassy. That week about 62,000 East German citizens had already left Czechoslovakia for West Germany, and thousands more were coming into Prague every day. When we drove by, the embassy garden was empty and the hundreds of refugees who had slept there in makeshift tents were gone, leaving behind a field of mud.

But everything was peaceful at the extraordinary Petschek Villa, home of the American ambassador, Shirley Temple Black, and her husband, Charlie. Ambassador Black had been in Prague for four months and had become close to Vaclav Havel and his circle. She was constantly urging him to move faster toward freedom and democracy. The license plate on her official car read “STB”—her initials, but also an acronym for the Czech secret police.

On Thursday, Nov. 9, we slept soundly in our room in the residence, the ambassador and Charlie at the other end of a long hallway. As we slept, the events in Berlin were unfolding.

On Friday morning, we turned on BBC radio at our end of the hall. The announcer reported that the Berlin Wall had been breached. We thought nothing of it, believing that yet another truck had barreled through one of the checkpoints. But it soon became clear that it was something quite different. Then our phone rang.

“Michael, this is Shirley. Come quickly. We have the TV on, and the Berlin Wall is falling.”

We walked down that long hallway into the ambassador’s suite. The ambassador was lying on the floor in some sort of a sleeping bag, and Charlie was sitting in a chair, watching CNN. We stayed with them for several hours, eating breakfast in front of the TV while the ambassador shared her memories of the Prague Spring of 1968, when she was stranded in Prague after the Red Army invaded.

We all knew we were witnessing a historic event but did not know what effect it would have on Czechoslovakia. The embassy had arranged for me to have lunch with four or five of Havel’s closest advisers, and we met in a local restaurant, all of us in a celebratory mood. The pilsner was flowing. Of course, the major question was what impact the fall of the wall would have in Prague. Surprisingly, each of the advisers insisted it would not have any impact, saying they were “years away” from anything like that happening. Their views were duly reported back to Washington.

Less than a week later, the Velvet Revolution began. By the end of the year Vaclav Havel was president. The fall of the Berlin Wall did not affect Poland and Hungary directly, but sped up developments in Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania and Yugoslavia. By the end of the year, all of Eastern Europe was free. The wall’s collapse served as a historic exclamation point: there would be no turning back.

After three years in U.S. Army intelligence, Michael Hornblow joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1966. He was the deputy director of the Eastern Europe/Yugoslavia office at State in 1989, and now lives in Fearrington Village near Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Marta at the Book Fair

Don Hausrath

Leipzig, German Democratic Republic

My visits to Leipzig came about before the German Democratic Republic melted away.

I loved visiting the book fair there, for any number of reasons. First, it was fun to visit a country that seemed to have been designed for a noir John le Carré thriller. Buildings still showed scars of World War II street fighting. We would drive through Checkpoint Charlie (“Sie Verlassen den Amerikanischen Sektor”) in our U.S. Information Service station wagon, its diplomatic plates bringing scowls to the faces of the GDR border guards.

East Germany heated their buildings with soft, sulfurous coal; and, thus, even with your eyes closed, you knew you were either in East Berlin or your high school chemistry lab. Dance halls in the GDR appeared to be staged by a 1930s movie director. Men and women sat at small square tables drinking beer. Men wore dark suits and danced with their hats on, a landscape of bouncing fedoras much like a snapshot of the interior of Union Square Station taken in the 1930s. Couples studiously followed Arthur Murray’s Magic Steps as they danced to “Begin the Beguine” and “All of Me.”

Our booth at the Leipzig Fair was always surrounded by fairgoers interested in the new books we displayed, which were of course banned from GDR bookstores. We piled as many titles as possible on a couple of tables and handed out glossy posters of the American Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution. These giveaways were prized in a country that did not then have access to such founding documents.

We were forbidden by the authorities to sell or give away our books but turned a blind eye to people who wanted to “steal” a book on display. In any case, security was tight; it was difficult once you had snitched a book to get it out of the building. Besides the casual browsers, there were serious readers sitting about the floor near our display, copying out sections of a book as fast as they could write. So it was that a woman of about 60, whom I will call Marta—I have forgotten her name—sat at our display each year, copying sections of books on American literature. She became a semiofficial fixture, and once I got her to stop long enough to share a coffee.

Marta turned out to be one of those sparkly ESL teachers one finds everywhere around the world. During the conversation, she explained that, like her fellow East Germans, she could not get access to the modern critical works she was salivating over in our display. She wanted her students to update their dated English vocabulary. English versus American literature came up, and she said her dream was to visit London—a common desire of the world’s English teachers. “But I can’t ever get to London,” she said. “My father was allowed out of the country to go to a trade show in Germany, and never returned. I can’t leave because of him. That’s how it works.” And she went back to her copying.

I later received a letter from Marta, thanking me for a book, The Word Finder, that I had mailed to her from my office in Vienna. After that, I never heard from Marta again. My wife and I left Vienna for Virginia three months before the wall came down, and two years later, when we visited Berlin, even the rubble of the wall was gone.

I stood staring at the vacant strip and found myself thinking of Marta. I suppose she went on teaching, but I hope she finally got to London. I think of that gift of The Word Finder, and that sentence about “words that are evocative, that stimulate and unfurl the wings of the imagination,” and pause at “unfurl,” a word that has special meaning for those who have lived in the walled city of East Berlin.

Don Hausrath was a Foreign Service officer with the United States Information Agency from 1971 to 1995. He was posted in Vienna in 1989 and now lives in Tucson, Arizona.

No News, Just Visas

Annie Pforzheimer

Bogotá, Colombia

When the Berlin Wall fell, I was one month into my first tour, as a vice consul in Colombia. There were visas and more visas, using counterfoils and a hand-stamped metal plate, frequent guerrilla-inflicted power outages and phones that didn’t give a dial tone for more than a minute after you picked them up. In Barranquilla in November 1989, the newspapers were full of the drug war and the fact that a girl from a poor part of the city was crowned Miss Colombia. No internet.

I’d like to say I was a witness to this world-shaking event, but it took weeks for it to reach our media and to really sink in. And after it did ... more visas.

Annie Pforzheimer, a recently retired career diplomat with the personal rank of Minister Counselor, was the acting deputy assistant secretary for Afghanistan until March 2019. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Going with the Flow

Robert Hunter

Washington, D.C.

One morning in November 1989, as I recall, there was a major conference of the “great and the good” at one of the Washington think-tanks. Just about every American who was anyone in the field of European security was there, a couple dozen or so. We deliberated all morning about what was happening in what was then called “Eastern” Europe. Discussion was broad and deep, and we even got some things right about the future. But no one among us, no matter how learned and experienced, suggested that the Berlin Wall would open.

And we were right—for about four whole hours! I know of no one in the business—and I knew most of them at the time—who predicted this event, though I later met some people who didn’t know much of anything about Europe who claimed they had predicted it.

The lesson, of course, is that there is a natural inclination—if not compulsion—toward conformity (and attachment to stasis) in foreign policy. The Cold War had generated so much structure—physical (military and economic), political, analytical and psychological—and so many people (on both sides) had become “invested” in the Cold War, that its continuation for the indefinite future was the common assumption. The end of the war was virtually unthinkable, and people who did argue against the broad consensus on the Cold War were mostly marginalized.

Ironically, I had essentially predicted the process whereby the Cold War would eventually end in a book I wrote in 1969, Security in Europe (second edition, 1972). But I fell away from my own insights when I went into government and began to “go with the flow.” Another lesson there!

In November 1989 Robert Hunter was a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. He was a National Security Council staffer from 1977 to 1981 and served as U.S. ambassador to NATO from 1993 to 1998. He lives in Washington, D.C.

The Beginning of the End

Pierre Shostal

Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin

In the fall of 1989 I was director of the Office of Central European Affairs (EUR/CE), which covered the German-speaking countries and both West and East Germany, in Washington, D.C. I had planned a visit to several of our posts in November but had not at first intended to visit Berlin. As demonstrations in favor of freedom in East Germany gathered strength, however, I changed my plans.

While visiting U.S. Mission Berlin in West Berlin on Nov. 3, Harry Gilmore, our minister in that city, hosted a dinner attended by the mayor and other city officials. As the evening progressed, the mayor kept receiving reports of a demonstration planned for the next day in East Berlin organized by the union of artists and writers. Crowd size estimates grew with each passing hour until the mayor announced that half a million were expected to attend (as it turned out, perhaps a million came). I decided that I had to be there.

Crossing into East Berlin the next morning through Checkpoint Charlie, I saw large numbers of people streaming toward the site of the rally, the Alexanderplatz. All was quiet and orderly, and many people had brought their children, some even pushing baby carriages with babies inside. Along the streets leading to the Alexanderplatz, young people wearing armbands chanted “Keine Gewalt!” (No Violence!) It was an orderly crowd that stopped in their tracks when a traffic signal turned red. German discipline reigned and people did not seem worried.

Crossing into East Berlin the next morning through Checkpoint Charlie, I saw large numbers of people streaming toward the site of the rally, the Alexanderplatz. All was quiet and orderly.

–Pierre Shostal

At Alexanderplatz, a very large space, there was a huge crowd. There I met up with colleagues from our East Berlin embassy, Jon Greenwald and another officer. Musicians serenaded the gathering, and speaker after speaker proclaimed the people’s desire for more choice, the right to travel abroad and freedom from spying on them. One singer belted out a satirical song with the refrain, “Er ist immer dabei!” (He is always there!)—a reference to the secret police who monitored every aspect of their lives. Despite the seriousness of the issues, the crowd was good-humored and seemed optimistic.

East German police stood well away from the crowd, and no Soviet troops were visible, either. A month earlier, when Mikhail Gorbachev had visited East Berlin to help celebrate the 40th anniversary of the East German regime, he had made it clear that the regime needed to adopt a reform program like his own perestroika in the USSR. The East German leadership had strongly resisted such reform for years, but Gorbachev’s warning was that without reform, East Germany was on its own. The regime remained obdurate, but the public understood Gorbachev’s message and realized that Moscow was not going to crack down on them, as the Soviets had done in 1953 following a workers’ revolt.

That evening Jon Greenwald and I traveled to Dresden, where we attended a performance of Gluck’s opera “Orpheus and Eurydice” at the fabled Semper Opera House. Following the performance, the curtain parted, and all the musical and technical personnel appeared on stage. The lead male singer stepped forward and proclaimed that the country’s artists and musicians were with the entire population in demonstrating for freedom. The house exploded with cheers and applause.

Reflecting on what we had experienced that day, I realized that we had seen the beginning of the end of the East German regime. The people had lost their fear, and the regime had lost its nerve. Five days later the Berlin Wall was opened (it did not fall) by East German border guards, and Europe entered a new chapter of its history. The United States stood by our German friends to help make this happen.

Pierre Shostal served in the Foreign Service from 1959 to 1995. In 1989 he was director of the Office of Central European Affairs in Washington, D.C. Mr. Shostal lives in Alexandria, Virginia.

Checkpoint Charlie, one of the best-known border crossings during the Cold War, became a symbol of territorial and political division—between East and West, communism and capitalism, confinement and freedom. Berlin, 2015.

James Talalay

A Family Story

Christiane Armstrong

Budapest, Hungary

On the evening of Nov. 9, 1989, the phone rang in our living room in Budapest. My father was on the line from Germany: “You won’t believe this, the wall just came down.” He was right—I was completely surprised and astounded. In Budapest, our first Foreign Service posting, we didn’t have Western television, and I had not been able to follow the rapidly unfolding events in East Germany over the previous few days.

Of course, we knew what had happened that summer in Hungary. We knew that the West German embassy had been flooded by hundreds of East Germans hoping that if they made it onto embassy grounds, they would somehow be able to get to West Germany. And then on Sept. 11, driving east through Austria on our way back to Budapest from a vacation, we were stunned by the sight of hundreds of Trabis, East Germany’s “people’s car,” going in the opposite direction.

Hungary had, indeed, opened its borders that day. I clearly remember being overjoyed for the East Germans who were suddenly able to leave the Eastern bloc—and envious because we were on our way back to that drab world. As much as I enjoyed our posting in Budapest, with marvelous colleagues and a fantastic ambassador, I could never share our American embassy friends’ enthusiasm for, as they saw it, the “quirkiness” of a communist country.