The Road Back to Tehran: Bugs, Ghosts and Ghostbusters

A veteran FSO and authority on Iran explains what it will take for Washington to “get it right” when U.S. diplomats finally return to Tehran.

BY JOHN W. LIMBERT

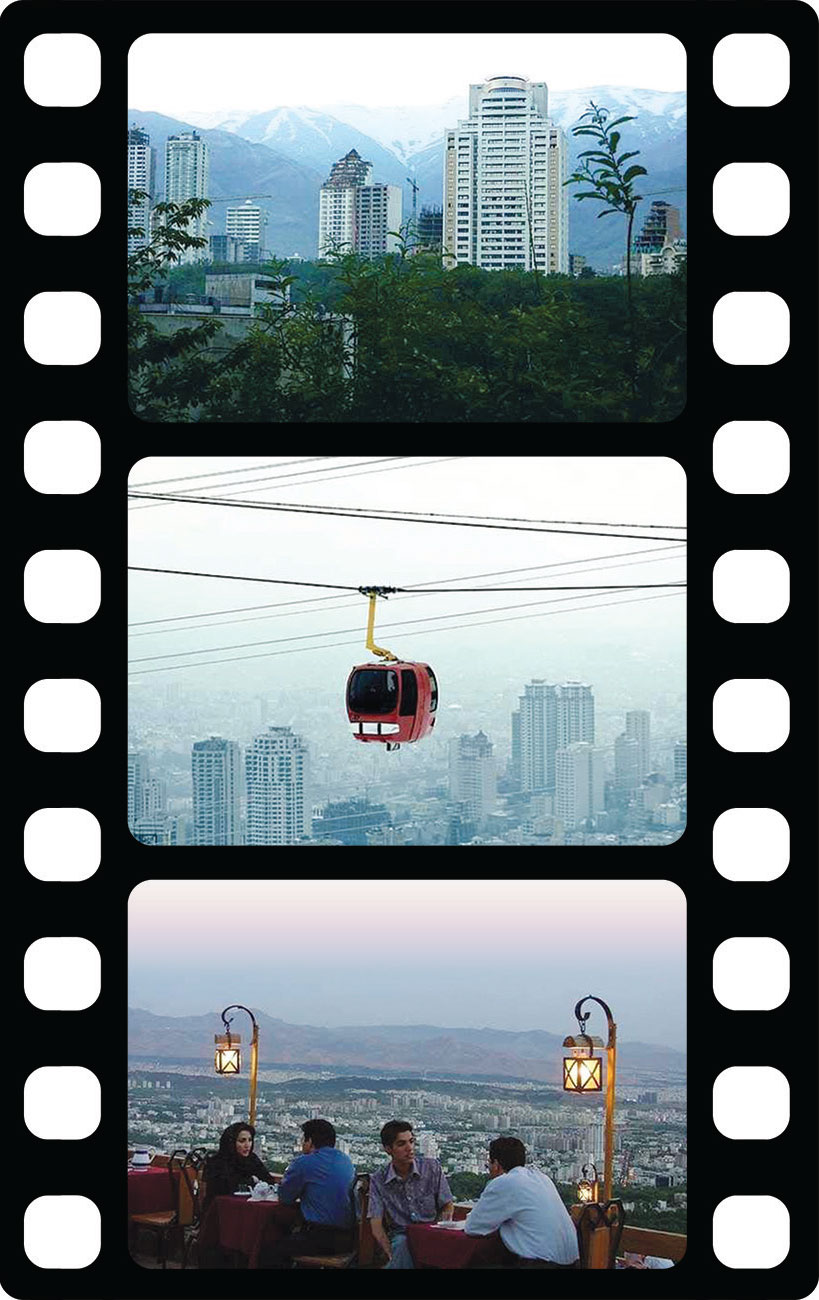

Top: Downtown Tehran. Middle: Tochal telecabin, the world’s longest gondola at Tochal Complex recreation center north of Tehran. Bottom: One of the city’s numerous café restaurants.

Courtesy of Mark Lijek

NPR: Is there any scenario under which you can envision, in your final two years, opening a U.S. embassy in Tehran?

I never say never; but I think these things have to go in steps.

— President Barack Obama, in an interview with

National Public Radio, December 2014.

In 2010, I asked the State Department’s Iran watchers, then gathered in Washington, D.C., which of them would volunteer to serve at a reopened diplomatic post in Tehran if the opportunity arose. All said they would.

None of them had ever set foot in Iran; but they had looked into a new world through windows of language, film, policy argument and, most important, Iranians they had met in Dubai, Istanbul, Baku, Berlin and elsewhere. They had obviously caught the antibiotic-resistant “Iran bug,” and a fascination with the intricacies and contradictions of that country and its civilization had taken root in their systems.

Sooner or later, our Foreign Service colleagues will return to Tehran. But while essential for effective service in Iran, their brains and enthusiasm cannot by themselves carry a renewed diplomatic tie. They will need support from the State Department in the form of a serious “Iranist” career track and an ability to deal with the potent ghosts that haunt both sides in the American-Iranian relationship.

The (Incurable) Iran Bug

The Iran watchers have encountered conflicting realities that both puzzle and attract them. Many of the Iranians they have met are highly educated and creative people, who produce brilliant films, paintings and poetry, and who sometimes turn their creativity to concocting the most bizarre conspiracy theories. The result was sometimes shock, but more often fascination. The watchers are like people who create a Jerusalem, Mecca or Karbala in their imaginations long before there is any chance of making a pilgrimage. They have never been to Iran, but the idea of Iran has captured them.

I recognized this virus, because I had caught it 45 years earlier, during Peace Corps training in Iran in the summer of 1964. At first, the beauties, subtleties and mysteries of the Persian language—despite endless drills—were a revelation. I realized that we were in for something unexpected one evening when playing Monopoly with our Iranian language teachers. I had never witnessed monopoly played this way: the rules became matters of mood and nuance. There were discussions about what number came up on the dice. Money and property would change hands mysteriously. A stodgy game became, in Iranians’ creative hands, unpredictable, and I began to suspect we were headed for unfamiliar territory that carried the promise of surprises.

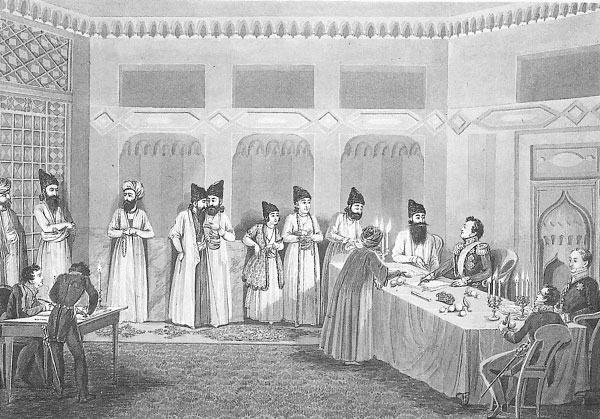

Under the Turkmanchai Treaty, ending the Russo-Persian War of 1826-1828, Russia reasserted its dominance in Persia. In addition to significant territorial concessions, Iran was forced to accept commercial treaties with Russia as Russia specified and lost rights to navigate the Caspian Sea and its coasts.

Wikimedia Commons

Our watchers may not have been aware that they have many predecessors who caught the same incurable infection: the British scholar E.G. Browne and the American scholar Richard Frye; the translator Dick Davis; the American political scientist Richard Cottam; the British writer Christopher de Bellaigue; the French geographer Bernard Hourcade; and the American writer Terrence O’Donnell.

Before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the American Foreign Service had sought to immunize itself from the Iran virus. The Service never produced Iran specialists. By accident or design, young officers such as Arnie Raphel learned Persian, served two or three years in Iran and, driven by their own intelligence and curiosity, picked up basic knowledge of Iranian history, culture and politics. After Iran, however, they were sent elsewhere, never to serve in the country again.

The result, well-documented in studies such as Professor Jim Bill’s The Eagle and the Lion, was that the State Department had trained no cadre of Iran experts to fill senior positions either in Washington or Tehran. Bill has traced how many Tehran embassy officers based their reporting on what they heard from a narrow circle of English-speaking, upper-class Iranians, most of whom were unaware of the realities of their own society. To paraphrase Winston Churchill: “Never have so many known so few who knew so little for so long.”

Getting It Right (and Wrong)

An Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. oil well in Iran, 1909. Exploitation of Iranian oil began in earnest in 1901 with the D’Arcy oil concession, backed by Great Britain as a way to push back against Czarist Russia’s influence in Persia.

Hulton Archive / Stringer / Getty Images

When our colleagues finally go back to serve in Iran, will we get it better? We will, if we can combine the enthusiasm and brains of the Iran watchers with a support system that supports. Such a system will need a cultural shift in the department in which our “Iranists,” wherever they are serving, can look forward to a rewarding career track. Getting it right will require still another cultural shift, in which people with insight into Iran and into Washington policy issues read their colleagues’ reporting and respond to it.

Two personal anecdotes illustrate the problem of support. In the early 2000s, while serving in Mauritania, I could read in my email unclassified reports on Iran from the consulate general in Dubai thanks to our embassy’s being on some collective address list. (Nouakchott had no classified email in those days.) The reports were full of exceptional insights, and I would send notes to the author praising his work and suggesting further questions to pursue. I later learned that my notes, from the remote West African coast, were almost the only response he received to his excellent messages.

A decade later, when serving as deputy assistant secretary for Iran in the State Department’s Near Eastern Affairs Bureau, I was reprimanded for sharing notes from National Security Council meetings on Iran with the watchers. I was told: “We must keep them [our colleagues] in the dark, lest we ourselves be excluded from the meetings.”

For now, the question “What happens when we send American diplomatic personnel to Tehran?” remains hypothetical. But at some point, our people will go back to an interests section or a reopened embassy in Tehran, and diplomats from the Islamic Republic will return to Washington. As we are now seeing with Cuba, no estrangement lasts forever. And when former enemies do begin to talk, they will soon ask themselves: “What were those decades of enmity about? Why did we waste so much energy annoying each other?”

Before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the State Department had trained no cadre of Iran experts to fill senior positions either in Washington or Tehran.

Ghosts in the Way

Our colleagues’ return, however, still faces an enormous obstacle: the presence of potent ghosts that haunt both sides in the American-Iranian relationship. See them or not, acknowledge them or not, the ghosts are there and will make their presence known. If we ignore them, they will still haunt us and work their spells.

Perhaps Secretary of State Cyrus Vance did not see the ghosts in October 1979 when, despite the explicit advice of his chief of mission in Tehran, he urged President Jimmy Carter to admit the ailing, deposed Mohammad Reza Shah to the United States. Asked by Carter why he was ignoring the views of the embassy, Vance said that we would tell the Iranians that the shah was in the United States “only for medical treatment”—there was “no political purpose” behind the decision.

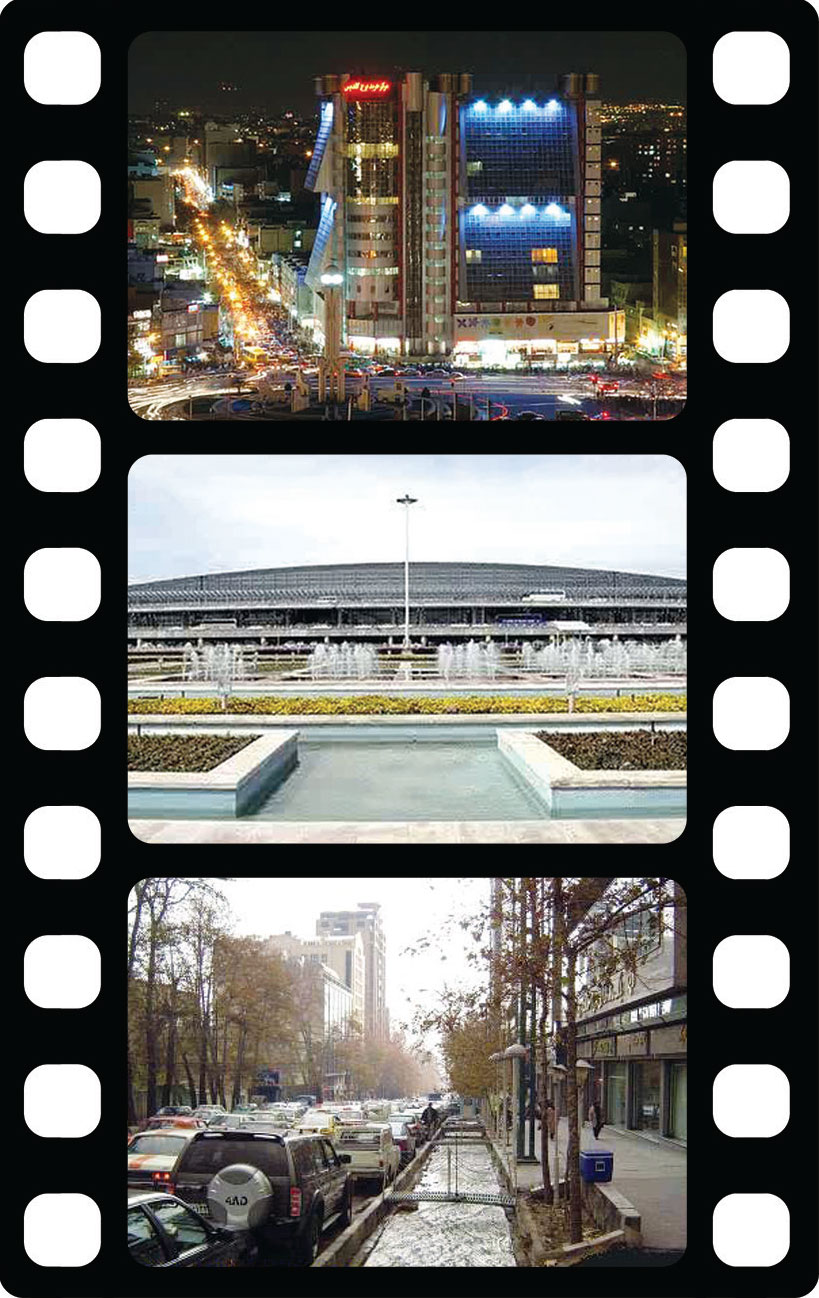

Top: Downtown Tehran at night. Middle: Tehran Imam Khomeini International Airport. Bottom: Valiasr Street, a main shopping area that separates Tehran’s eastern and western sectors.

Courtesy of Mark Lijek

Did Cyrus Vance and his colleagues think that anyone in Iran would accept this explanation? Did they believe that the ghosts of August 1953, when the CIA helped stage a coup that removed the nationalist prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, had been exorcised and had lost their power to work mischief? Were they even aware of those events and their place in the Iranian political canon?

Combined with these simmering resentments of history was an explosive present. The revolutionary movement that triumphed in February 1979 had not brought Iranians the promised paradise. It had not even brought them peace. There was ongoing strife in universities, on the streets and in those provinces dominated by ethnic minorities.

Nationalists and liberal intellectuals were complaining about the new authoritarianism; leftists were beating the anti-American drum and clamoring for more confiscations and executions; with backing from powerful clerics, right-wing thugs called hezbollahi (God’s partisans) were beating up journalists, women and anyone who questioned their slogan: “Rahbar, faqat Rouhollah; Hezb, faqat Hezbollah” (The only leader is Rouhollah [Khomeini]; the only party is the Hezbollah).

With the revolution in such trouble, the hunt was on for scapegoats. Since the new rulers were not about to admit their own failings, the difficulties had to be the work of foreigners and their agents. Americans became the most obvious target, and assassinations, explosions and disturbances were described as the work of “American mercenaries.”

Yet, in a case study of obliviousness, the administration ignored these realities of both past and present and decided in October 1979 that it would be a good idea to pour gasoline on the glowing embers of Iranian politics by admitting the shah to the United States.

And just as U.S. Chief of Mission Bruce Laingen had predicted three months earlier, the results were: (1) collapse of the relatively moderate provisional government of Iran; (2) end of any contact between the U.S. government and the new rulers of Iran; and, (3) end of the American diplomatic mission in Tehran.

An Iranian soldier guarding against chemical weapons during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988).

Wikimedia Commons

The Curse of Obliviousness

Americans have no monopoly on ignoring ghosts in the room. In early 2014, despite quiet warnings from Washington, the Islamic Republic, under its new president, Hassan Rouhani, nominated Hamid Abutalebi to be its ambassador to the United Nations. It turned out that Abutalebi had been one of the “Moslem Student Followers of the Imam’s Line” who had seized the U.S. embassy in November 1979 and, with the support of the Iranian authorities, held its staff members hostage for more than 14 months.

The appointment reopened a wound that had been festering for 35 years, provoking a firestorm of reaction in the United States that seemed to catch the Iranian side unaware. One can only ask: Were those who nominated Abutalebi aware of his past? If they were, why did they ignore the ghosts of that time and misread the damaging effects of their choice, even on those Americans who were willing to give Rouhani and his new team the benefit of the doubt? What were they thinking when they made such a nomination? Were they thinking at all?

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s comments more than a year earlier provide some insight into how some Iranians deal—or do not deal—with the ghosts. At a private discussion with American academics in September 2012, during his visit to the United Nations General Assembly, Ahmadinejad spoke about the need to end the “negative mentality” infecting the U.S.-Iranian relationship that frustrated all efforts at change.

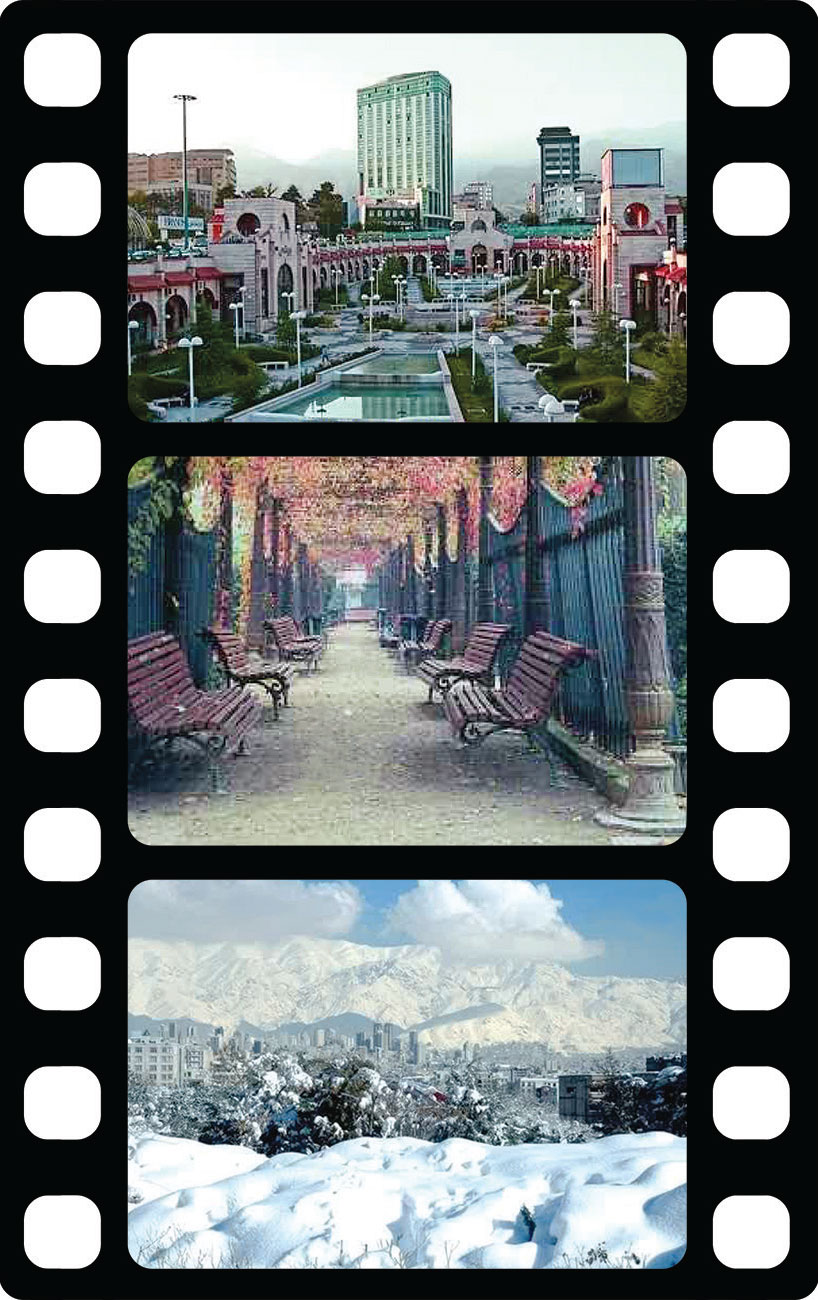

Top: A luxury shopping center at Sheikh Bahaei Square in the Vanak area of Tehran. Middle: One of the city’s many parks. Bottom: A panoramic view of Tehran in winter.

Courtesy of Mark Lijek

At the meeting I asked him: “Why not do as your predecessor (President Mohammad Khatami) did, and address the running sore of the 1979 embassy seizure and hostage holding? For example, you could end or limit the annual demonstrations on Nov. 4, which pretend that ugly action was a positive thing. Such an act would be a powerful first step toward eliminating that negative mentality you have deplored.”

Ahmadinejad appeared puzzled by the question. He seemed to be thinking: “Where did all that come from? What do those events of 33 years ago have to do with anything today?” His response, which completely missed the point, was: “Well, you were treated all right, weren’t you?”

The problem is obliviousness. In this way of thinking, whatever happened then has nothing to do with today. The events of 1979 happened “a long time ago in a galaxy far away.” The far savvier Rouhani, Ahmadinejad’s successor, could be just as unaware of realities past and present and could nominate Abutalebi, a step which turned into a fiasco for the Iranians.

Of course the Iranians are not the only oblivious ones. In 1973, President Richard Nixon also set a standard for thoughtlessness when he nominated the former CIA chief, Richard Helms, to be ambassador to Tehran. Did Nixon understand (or even care about) the symbolism of his action and the fact that this appointment would be seen in Iran as a gratuitous humiliation? The message was: “You Iranians may think you’re a sovereign country. But I am sending you a reminder that you are not. Now I will show you who is really the boss.”

The (Right) Road Back: Bring the Ghostbusters

No enmity is forever. It took decades, but the U.S. established diplomatic relations with the USSR and China after their revolutions when it was in both sides’ interest to do so. Cuba is the latest case, although in Havana there has long been a large U.S. diplomatic presence in the form of an interests section. In the case of Iran, the reasons for the 35-year estrangement are sometimes difficult to understand when balanced against the need to engage—not as friends, but as countries with matters to discuss—on subjects such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Sunni extremism.

When we do send our people back, and when Iranian diplomatic personnel appear in Washington, teams of “ghostbusters” who know how to deal with the phantoms of the past should be present. On our side, here are some guidelines that will help us get it right this time.

The problem is obliviousness. In this way of thinking, whatever happened then has nothing to do with today.

● Move carefully. We should not be in any hurry. As much as possible, we need the assurance that the events of 1979 will not be repeated, and that the Iranian authorities will fulfill their responsibilities under international law and practice. The Iranian domestic political scene remains an arena of competing groups, which are looking for opportunities to embarrass their rivals. We need to be sure that at the first setback (and there will be setbacks) one group or another will not be able to act out “Hostages II,” as some groups did when they seized the British embassy in Tehran in November 2011.

● Listen to those who know. In Washington there are many competing voices on Iran, and the views run from “It’s all our fault” to “They are evil people.” Our diplomats in Iran will not know everything, but at least they can provide a measure of first-hand reality useful in evaluating the ideas peddled in op-eds and think-tanks inside the Washington Beltway.

● Be serious about supporting our people. Create what the department has never had: a cadre of Iranists. Six or nine months of Persian study at FSI and a two-year posting does not an Iran expert make. That is a useful beginning, but if there is no coherent follow-through, the time and money spent will be wasted. Officers need serious language and area studies training, both inside and outside the government. Beyond a posting in Iran, they should have related postings in the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, Central Asia, the Caucasus and elsewhere. Their Washington assignments should also be relevant. There should be cross-training in other Middle Eastern cultures and in Arabic and the Turkic languages. Such a program is not for everyone. We are going to need serious and committed people, not just anyone who shows up or seeks to rescue a career.

Former Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh (front right). The democratically elected prime minister was removed from power on Aug. 19, 1953, in a coup d’etat supported and funded by the British and U.S. governments. He was imprisoned for three years and then put under house arrest until his death in 1957.

AFP / Getty Images

● Don’t do or say stupid stuff. We must be aware of the effects of our words and actions in an Iranian political culture that sees itself as the humiliated victim of powerful outsiders—British, Russian and American. We should avoid talking about “Iranian paranoia” or “Iranian DNA.” We will need lots of empathy to understand Iranian views of events and understand what lies behind sometimes extreme rhetoric. We should acknowledge the symbolic power of the ghosts of the Iran-Iraq War, the 1964 status of forces agreement controversy, the coup of 1953, the D’Arcy oil concession of 1901 and even the Turkmanchai Treaty of 1828, in which the Qajar rulers of Persia gave up their sovereignty to Czarist Russia.

● Listen and be very patient. Since 1979, Iranian political discourse has too often consisted of reciting lists of complaints against the United States. Such recitation is both frustrating and unproductive. Yet a patient American listener needs to acknowledge, “Yes, I understand that you have grievances.” For a time, repeating these sterile lists can make dialogue very difficult. As long as we stay in the room and listen, however, sooner or later it will be possible to move into something more productive.

That move happened with the nuclear negotiations in 2013. We waited out the rhetoric, remained professional and eventually found ourselves in “productive” discussions with Iranian officials for the first time in 34 years. The change has not led to a quick resolution of problems, but on the symbolic level it has been an enormous shift from more than three decades of trading insults, threats and slogans.

Sooner or later, our Foreign Service colleagues will return to Tehran. They may even reoccupy the “[Loy] Henderson High” complex on Taleghani (formerly Takht-e-Jamshid) Avenue, although exorcising the ghosts that haunt those buildings may take even more time.

When they do return, both sides should have learned their lessons: that a host government, even if it calls itself “revolutionary,” is responsible for the safety and security of foreign diplomats; and that behind Iran’s positions and policies lies a real and imagined history of defeat, exploitation and humiliation.

All candidates for an embassy post in Tehran should be asked: “What is the importance of Turkmanchai?” If they don’t know, they don’t go.

Read More...

- Full Transcript & Video: NPR News Interview With President Obama (NPR website)

- The U.S. and Iran: Mything the Point (The Foreign Service Journal, June 2007)

- Review - The Eagle and The Lion: The Tragedy of American-Iranian Relations by James A. Bill (Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1988)

- Iran and the United States: Getting to Yes (The Foreign Service Journal, June 2013)