Mozambique: When Diplomacy Paid Off

In the face of numerous challenges, diplomacy played a vital role in post-independence Mozambique and the Southern Africa region.

BY WILLARD DEPREE

Well before I presented my letter of credence as U.S. ambassador to Samora Machel, president of the People’s Republic of Mozambique, on April 16, 1976, it was already clear that my assignment would be a challenging one. Nine months earlier, on July 25, 1975, the State Department had informed Machel’s government that we wished to send an ambassador to Maputo—yet it took more than three months for him to approve the request.

The delay reflected stark divisions within the ruling party, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique. Many officials were unhappy with the U.S. government’s past support of the Portuguese during FRELIMO’s struggle for independence. Others resented Washington’s refusal to take a more active role in pressing for black-majority rule in Rhodesia and South Africa.

Some, including President Machel himself, were also angry about our support of ethnic groups in Angola who had taken up arms to prevent FRELIMO’s close ally, the Marxist Movement for the Liberation of Angola, from coming to power. Others feared the CIA might use the embassy as a springboard from which to create problems for Mozambique.

They were not the only critics of the diplomatic overture, either. Some members of Congress rallied behind the efforts of Senator Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) to block the opening of an embassy in Mozambique. Their argument could be summed up as: “Why should we spend U.S. taxpayer money opening an embassy in an unfriendly, Marxist country? What cooperation can we expect from a government that refers to the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, Vietnam and North Korea as ‘our natural allies’ and is so sharply critical of U.S. Africa policies?”

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s determination to proceed was rooted in his concern that after the U.S. withdrawal of its last troops from Vietnam the previous year, the Soviets might conclude that Washington would be less diligent in resisting the spread of communist influence in Africa, especially in the former Portuguese possessions. He chose Angola as the place to signal this was not the case, by furnishing arms to Bacongo tribal leader Holden Roberto and his followers.

Helms and his allies were unable to block the opening of Embassy Maputo. But they were able to insert language into the State Department and USAID authorization bills proscribing the expenditure of any development aid money in Mozambique. (Ethiopia and Uganda were also singled out.)

For its part, the Mozambique government instructed American personnel at our consulate in Maputo not to fly the American flag before my arrival. It also stipulated that when our embassy opened, there were to be no uniformed U.S. military personnel on the staff, precluding the use of Marine security guards.

Those first 12 to 18 months at post were indeed frustrating. My staff of eight and I seemed to encounter obstacles whatever we tried to do.

The Diplomatic Deep Freeze Gradually Thaws

Fortunately, the Department of State assigned Johnnie Carson, an exceptionally able officer, as my first deputy chief of mission. The political officers who were assigned to Maputo were some of the best with whom I have ever served. All three DCMs during my five years as ambassador in Mozambique went on to serve as ambassadors elsewhere in Africa: Johnnie Carson, who retired as assistant secretary of State for African affairs, in Kenya; Roger McGuire in Guinea-Bissau; and Bill Twadell in Liberia and Nigeria. (Two of my three junior political officers also eventually became chiefs of mission: Jimmy Kolker in Burkina Faso and Uganda, and Howard Jeter in Nigeria).

Those first 12 to 18 months at post were indeed frustrating. My staff of eight and I seemed to encounter obstacles whatever we tried to do. Rarely did ministers or senior government officials accept invitations to embassy functions. To travel almost anywhere outside Maputo required Mozambican government approval, which was not always forthcoming and took time even when it was granted.

Efforts to acquire rental property for our personnel proved difficult, as well. With the departure of the Portuguese, there was a lot of real estate on the market; but when we sought to sign our first lease, the government told us it was holding the property for one of their “natural allies,” who had expressed a “possible” interest in it.

Our repeated requests to see four American missionaries who had been held for months without charges were always turned down. Appointment requests for visiting U.S. officials were usually put on hold until they arrived in Mozambique, and then we were occasionally told that no appointment could be arranged.

A major disappointment was when the government said that a visit from Secretary of State Henry Kissinger would be “inopportune,” even though we offered two dates for such a visit. That turndown made me ask myself if those opposed to opening an embassy in Mozambique may have been right after all.

Meanwhile, the entire embassy staff was being closely watched. This was brought home to me three months or so after I had been at post. I had occasion to call on Pres. Machel to make another pitch for release of the American missionaries, or at least to be told why they were being held. I spoke in Portuguese, of course. After I had finished, Machel complimented me on my progress, which made me feel good—until he added, “But your wife is better.”

Through these meetings, I was able to establish a close working relationship with Machel.

I had no problem with this, for my wife was indeed better. But then he added, “There are five wives of ambassadors who have taken the trouble to learn and speak our language. The Bulgarian ambassador’s wife is best; your wife is second-best, and the Tanzanian ambassador’s wife is third.”

Wow! If the president of the country knows this much about the wives of ambassadors, you can imagine how closely you are being watched. Of course, it is possible that Pres. Machel may also have wanted to put me and my staff on notice not to be doing something we didn’t want the government to know about.

But after that first difficult year, the chill began to thaw. When our paths crossed at receptions and cocktail parties, Mozambican officials seemed more ready to engage in meaningful discussions. Ministers and senior government officials also began to show up at embassy receptions and accept invitations to lunch at my residence. And while the government never did permit us to see the four American missionaries they held for more than a year, they finally released them.

Getting Our Feet in the Door

Three developments help explain why the Mozambicans began to have second thoughts about their standoffish relationship with the embassy. First, the U.S. government was quick to respond to two humanitarian crises that struck Mozambique during its first two years of independence. A drought ravaged a wide swath of the most agriculturally productive provinces, and then major flooding hit many of those same provinces the next year.

The regime simply did not have enough food to feed its own people, much less the thousands of refugees from Rhodesia who had sought shelter in Mozambique. Since the ban on development aid to Mozambique did not apply to humanitarian aid, the United States was quick to offer assistance. We did not ask for a quid pro quo, but our prompt shipments of food, tents and other supplies were very welcome.

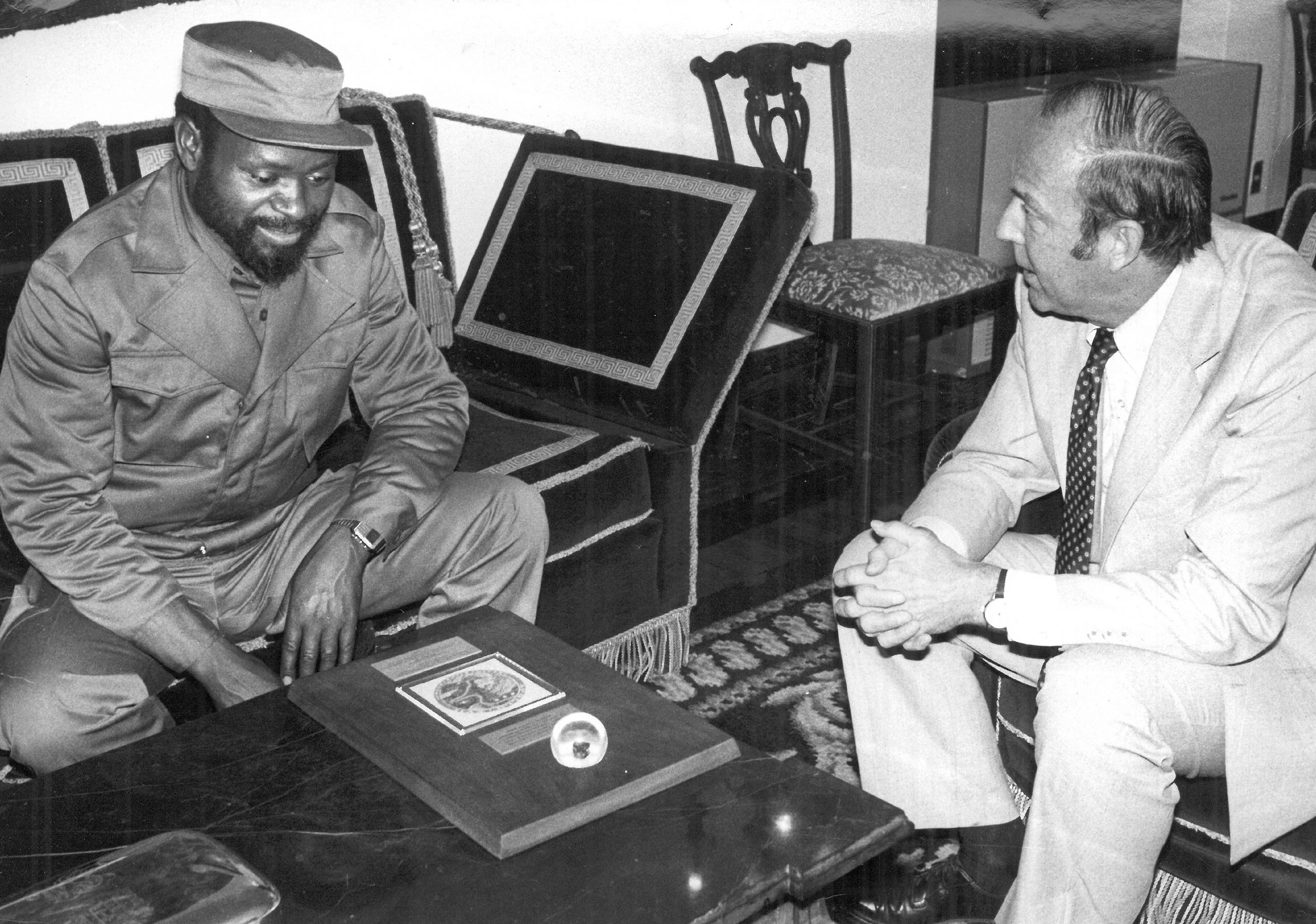

People’s Republic of Mozambique President Samora Machel meeting with U.S. Ambassador Willard DePree in July 1980.

Courtesy of Willard DePree

Second, the Mozambique government was becoming disillusioned with its “natural allies.” I came to understand this late in my second year as ambassador, when I received a call from Pres. Machel asking me to come in and discuss development aid. When political officer Jimmy Kolker and I arrived, we were welcomed not only by Pres. Machel, but by the minister of agriculture and other senior government officials, as well.

“You Americans know how to produce food,” Machel stressed. “Nobody is as good at this as you are. The Bulgarians are trying to help us grow food, but they have little to show for their work. In fact, we’re losing money supporting their efforts. Why don’t you come here and help us?”

He then asked his agriculture minister: “How many hectares of land in the Incomati River Valley can we let the Americans have?” The minister mentioned some astonishingly high figure, to which Machel interjected, “If that isn’t enough, we’ll double it. Prove that you can do it better than the Bulgarians.”

This was an enticing challenge, but one Machel obviously knew we couldn’t accept, given the ban on development assistance. Accordingly, I suspect he arranged the meeting to signal that his government was not so committed to Marxism as earlier rhetoric might have led us to believe. Whatever he may have had in mind, the meeting did highlight that disillusionment with their allies was beginning to set in.

We had already been hearing from other officials, for example, how disappointed the Mozambicans were with Soviet shrimp fishing off the coast. The Soviets did not appear to be sharing their take with the Mozambicans as they had promised, and their trawling methods were destroying some of the best shrimp-growing areas in the country. All this suggested that the Mozambicans might be more receptive to redressing the imbalance in their foreign policy posture. The embassy was eager to test this possibility.

With no prospect of military victory in sight, Pres. Machel began to explore other ways to bring about a change of government in Rhodesia.

The Rhodesian Opening

But the development that probably did more than anything else to spur FRELIMO to look for ways to improve its relations with the U.S. was the fact that the war in Rhodesia, which shares an 800-mile border with Mozambique, was not going the way the Machel government had hoped. They had thought that once they became independent and could offer sanctuary and military support to the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army forces engaged in the fighting inside Rhodesia, the war would soon be over. Instead, the white Rhodesian government of Ian Smith began carrying out retaliatory bombings. It also stirred unrest inside Mozambique by supporting dissidents from the former Portuguese forces, a small number of whom had already organized and taken up arms in opposition to the government in Maputo.

With no prospect of military victory in sight, Pres. Machel began to explore other ways to bring about a change of government in Rhodesia. He knew the British, with the encouragement of the Carter administration, were seeking to persuade the government of Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith to agree to a ceasefire and free and fair supervised elections, with the British agreeing to turn over power to whoever won the election. Pres. Machel decided to explore this option; but to do so, he needed to elicit U.S. cooperation.

Fortuitously, on June 7, 1977, President Jimmy Carter announced that the United States would not lift its sanctions against the Rhodesian government. Soon thereafter, Pres. Machel let me know that his government was prepared to work closely with us and the British to bring about a ceasefire and free and fair elections in Rhodesia. He said he hoped we would agree to keep what we were doing out of the public eye. Toward that end, the foreign ministry would not be involved; instead, he designated two of his aides, Sergio Viera and Fernando Honwana, to work with us on any actions we might jointly decide to undertake.

Machel took these negotiations seriously. He met with the two individuals chosen by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Pres. Carter to brief the interested parties on the progress of the negotiations (Ambassador Stephen Low for the State Department). Pres. Machel suggested people they might wish to see in support of their negotiations. He also met frequently with my British counterpart in Mozambique, Ambassador John Lewen, and me to offer further suggestions and be brought up-to-date on the state of play.

Through these meetings I was able to establish a close working relationship with Machel. At one point, the president called me in, closed the door and asked if I knew of any American who was a friend of Abel Muzorewa, a highly regarded bishop of the United Methodist Church who was serving as president of the African National Council, an organization of Rhodesians seeking a political settlement to the fighting in Rhodesia. Machel wanted to send a personal message to the bishop, but did not want to put what he was requesting in writing. He also made clear that if his overture became public, he would deny it.

Pres. Machel said he hoped he could dissuade the bishop from joining forces with Joshua Nkomo and other tribal leaders who, Machel thought, would work against what he and we were seeking to accomplish. I knew a few American academics who had become friends of the bishop when he had studied in the United States. One of them came to Maputo and, after hearing what Machel was seeking from Bishop Muzorewa, agreed to deliver the message and to report back to Machel. Though he was disappointed in Muzorewa’s response, Machel’s readiness to turn to us for help on such a sensitive issue is a good indication of how dramatically Mozambican reservations about having anything to do with the United States had changed.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was so appreciative that she invited Mozambique to become a member of the Commonwealth.

Bringing the Parties to the Table

In the summer of 1979, the British government concluded that it was time to concentrate on getting all the interested parties—Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith; the insurgents, led by Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo; the South African government; the United Nations and all the states neighboring on Rhodesia—to commit to a ceasefire. The parties to the agreement would then be responsible for maintaining law and order during a six-month transition to elections, including the demobilization and disarming of the Rhodesian forces and the insurgents.

Prime Minister Thatcher invited all the interested parties to a meeting at Lancaster House in London in September. Pres. Machel sent Fernando Honwana as his personal representative. After several days of negotiations, the British called for a vote. All those attending were prepared to sign on. But there was one delegate who refused to sign—Robert Mugabe, leader of the Mozambique-based ZANLA. Mugabe’s concurrence was crucial, for it was his forces that were doing most of the fighting inside Rhodesia. It appeared that the conference would break up without agreement; some delegations were already booking tickets to return home.

It was at this point that I received a night action cable from the State Department, with instructions from Pres. Carter to ask Pres. Machel if he would intervene and pressure Mugabe to sign onto the negotiated Lancaster House accord. Time was of the essence, since once the delegations departed, it would be difficult to ever reach agreement on a ceasefire and elections.

I called Machel’s office at once to request a sit-down, but was told the president was in a Cabinet meeting and a face-to-face would be arranged as soon as he was free. Rather than wait for a return call, I asked if I could go to where he was meeting so I could catch him when he came out. This was granted and, as soon as he spotted me, Machel came over to ask what I was doing there.

Once he realized the urgency of my instructions, he didn’t hesitate, but got in touch with Mugabe at once. Pres. Machel wanted a settlement as much as we or the British did. He couldn’t understand why Mugabe was refusing to sign. “He’s won!” exclaimed Machel. “He is Shona, the major tribal grouping in Rhodesia. ZANLA will win the election.” I immediately returned to the embassy, reporting that Pres. Machel had agreed to do what Pres. Carter had asked him to do.

Shortly thereafter, I received a message from Assistant Secretary for African Affairs Dick Moose notifying me that agreement had been reached at Lancaster House, and that the British were crediting Machel with having made the difference. I learned later that the British had listened in on Machel’s call to Mugabe, hearing the Mozambican president stress even more forcefully the arguments that he used with me that same day for why Mugabe should sign.

Prime Minister Thatcher was so appreciative that she invited Mozambique to become a member of the Commonwealth, the first time membership had been offered to a country that was not a former British colony or possession. And, much to the surprise of many, Mozambique agreed to become a member and has been one ever since. Sometimes diplomacy pays big dividends!

Read More...

- Ambassador Willard De Pree Oral History Interview with ADST (The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training website)

- U.S. Relations with Mozambique (U.S. Department of State Fact Sheet)

- Hard Times for the Africa Bureau, 1974-1976: A Diplomatic Adventure Story (American Diplomacy Publishers website)

- Cold War in Southern Africa: White Power, Black Liberation (Routledge, 2009)