Being There: Camp David, 1978

Reflections

BY FRANK FINVER

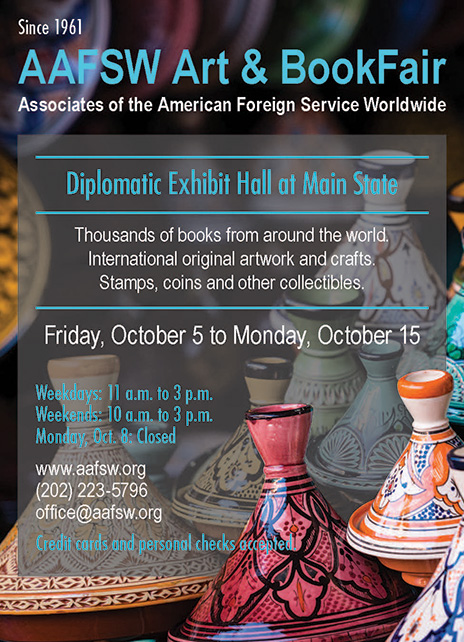

Frank Finver, in 1978, stands in front of the Camp David sign at the entryway to the mountain facility.

Moshe Milner

“Here’s a map. Pack clean underwear, because you might need to stay overnight.” So I was instructed a couple weeks after starting my internship with the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., as a postgraduate student at American University. And so it was that on Sept. 5, 1978, I was driving north toward Thurmont, Maryland, into the Catoctin National Park.

I waited in a small, mountaintop parking lot with a snoozing Israeli general in the passenger seat from noon until dusk, when a white U.S. Navy sedan pulled up and a voice said simply, “Follow me.”

We came to an entrance with the iconic wooden “Camp David” sign illuminated and waited some more. I sensed some movement and faint rustling nearby and then spotted camouflaged Marines combing the woods for intruders. (They would later apprehend a number of infiltrators, who possibly had malign intent.)

For the next 12 days I shuttled bodyguards and principals around and ran assorted errands from 5 a.m. to 2 a.m., when I returned down the mountain to the Hagerstown Holiday Inn for a few hours of sleep.

All was going well until the morning a large and compulsive security agent named Doron insisted on driving, and proceeded to greatly exceed the strict 10-mph limit—just as Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and his party were taking their pre-dawn stroll nearby.

The red-faced camp commander sprang into Doron’s window, forcefully explaining that should he opt to drive again on the premises, he would be on the next flight home.

A white U.S. Navy sedan pulled up and a voice said simply, “Follow me.”

We were setting up our trailer offices (I still have the wooden Israeli delegation sign in my attic) when Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan dropped by to chat and pose for pictures, courtesy of Moshe Milner of Time magazine.

Milner spotted Prime Minister Menachem Begin walking around and coaxed me to approach him, which I did.

Me (in Hebrew): I read your book.

Begin (also in Hebrew): Which book?

Me: The Revolt.

Begin: Did you fall asleep while reading it?

Me: Of course, I mean no!

(He later visited our trailer and borrowed my book, Foreign Policymaking in the Middle East, co-authored by R.D. McLaurin and my professor, Mohammed Mughisudin, which gave me another excuse for delaying my exam.)

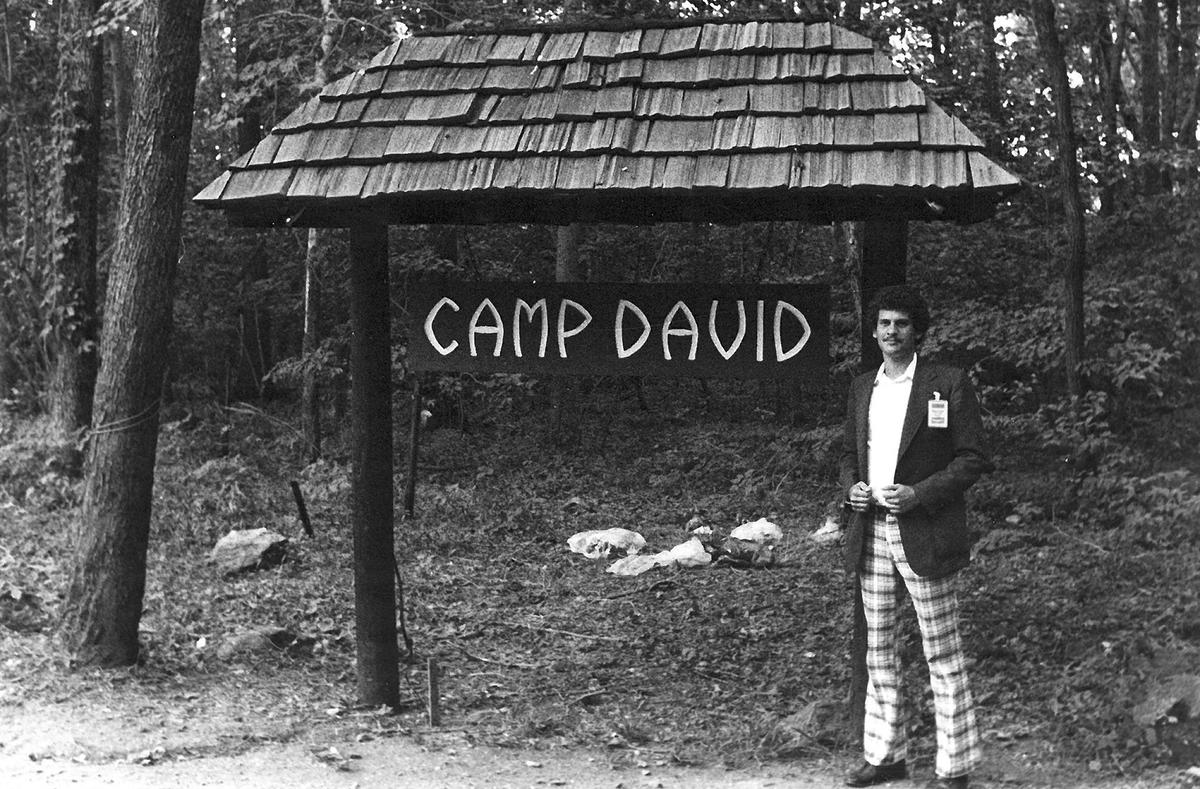

A relaxed moment at Camp David: Moshe Dayan (center) with Susie Maltzmann, secretary to Israeli Ambassador to the United States Simcha Dinitz, and an Israeli security guard outside the Israeli delegation’s office/communications trailer.

Frank Finver

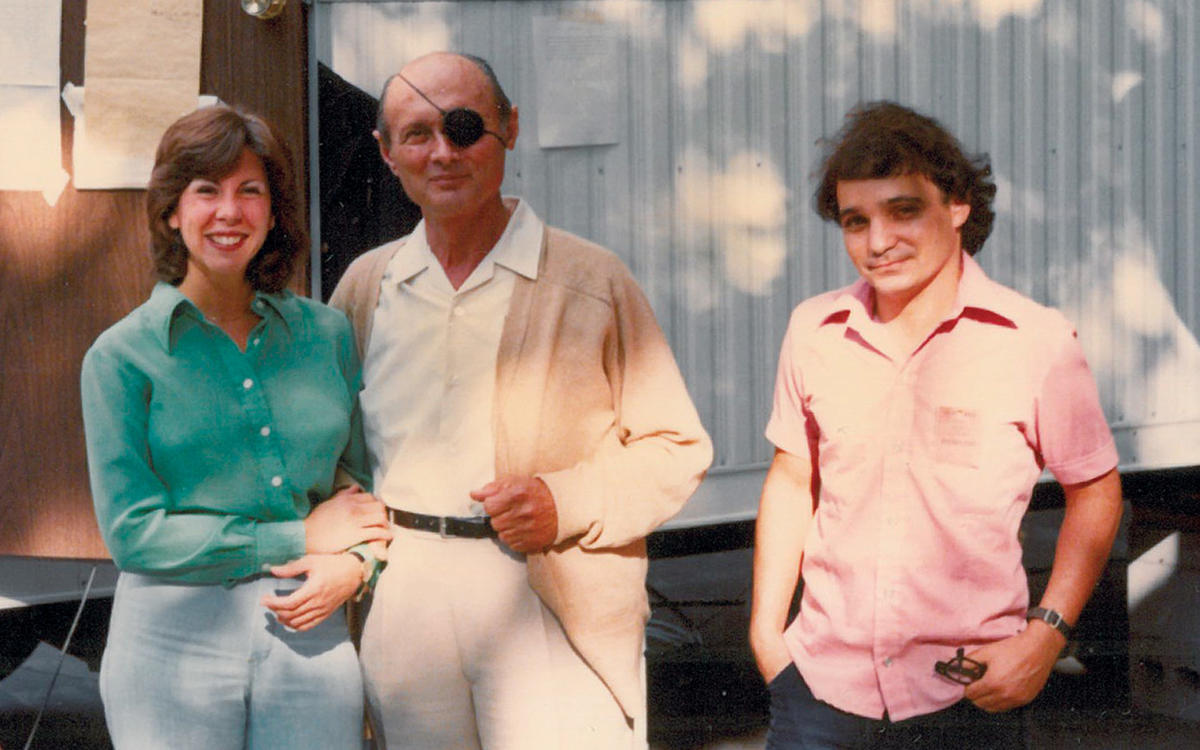

On the evening of the second day, everyone turned out at the parade grounds between the field house and the helo pad, where the U.S. Marine Drum and Bugle Corps played a medley of “New York, New York,” “I Believe” and the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Then—with President Jimmy Carter, President Sadat and Prime Minister Begin standing stiffly at attention on a reviewing stand—the Marine Silent Drill Team put on a remarkable show of dexterity and precision by twirling, tossing and catching their weapons (with fixed bayonets) in rapid succession. Impressive as it was, the martial display was a tad incongruous for a peace conference; but I guess Peter, Paul and Mary were not available.

The next evening, Sept. 8, the Israeli delegation, joined by the Carters and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, gathered for Shabbat dinner at Hickory Lodge. Spirits were high—lots of singing, eating and joking.

One morning I went to see Israeli Defense Minister Ezer Weizmann, who was not feeling well and resting in his cabin.

“Who’s there?” Weizmann called out in Hebrew as I tried to quietly enter.

“They asked me to check on you,” I answered.

“You’re a bloody Yank, huh?” he said. “Hand me that goddamned bottle of cognac. Only thing that helps with this cold!”

Later in the week, I heard that Weizmann made quite a scene while leaving a screening of the graphic World War II film “Patton.” He had dramatically launched his crutches (he had been in a car accident in Israel) into the bushes, exclaiming: “That [carnage of war] is what we can expect if we don’t reach an agreement!”

After a few days of running errands, reading, playing basketball with the Marines, I drove a site advance team 45 minutes down the hill to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. We reviewed the battlefield site for a VIP visit the following day, which President Carter conducted with minimal assistance from a Park Ranger.

Even on the weekend, it was business as usual for the delegations; but tension was palpable as rumors circulated on Saturday, Sept. 16, that Sadat was packing his bags. Late that evening, I strolled up to our parking area, where some colleagues sat grim-faced in a semicircle around a TV placed under the stars on this warm night.

To my delight, “Saturday Night Live” was on, and Garrett Morris, Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi were masterfully portraying Sadat, Carter and Begin.

Suddenly Carter’s top aides, Hamilton Jordan and Jody Powell, approached, and I briskly fetched more chairs and a couple of Budweisers. Soon they, too, were guffawing with delight.

Sunday was eerily quiet, with failure and despair in the air. Time had flown by, but now seemed stopped; and Camp David seemed confining. That, however, changed instantly late Sunday with a burst of activity.

The three leaders stand at attention during the U.S. Marine Drum and Bugle Corps concert and drill team performance at the Camp David parade grounds on Sept. 7, 1978.

The White House

President Anwar Sadat, President Jimmy Carter and Prime Minister Menachem Begin clasp hands happily at the White House ceremony where the Framework for Peace in the Middle East and the Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty Between Egypt and Israel were signed on Sept. 17, 1978.

The White House

“Frank, we’re leaving. Go check Birch in case Begin forgot something.”

I saw that Prime Minister Begin had left his hat, coat and some notes (but not my book). I gathered his stuff and began to run toward a large Marine helicopter preparing to lift off.

Klieg lights burst on as I neared the spot, blinding me and casting Begin and company in silhouettes, from which the PM spoke: “Thank you. Will you be joining us in the helicopter [ride to the White House]?”

“No, he’ll meet us there,” someone answered for me.

I was soon flying down the mountain and toward D.C. in my embassy sedan, the Israeli security chief snoring next to me. The signing ceremony was broadcast on the radio.

“The first document that we will sign is titled ‘A Framework for Peace in the Middle East,’” President Carter intoned. “[It] is quite comprehensive in nature, encompassing a framework by which Israel can later negotiate peace treaties between herself and Lebanon, Syria, Jordan ... (and) provides for the realization of the hopes and dreams of the people who live in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and will assure Israel peace in the generations ahead.”

President Sadat spoke of the “spirit of Camp David,” and Prime Minister Begin called it unprecedented, “a unique conference, perhaps one of the most important since the Vienna Conference in the 19th century.

Six months later, on March 26, 1979, I put my raincoat down (á la Sir Walter Raleigh) on the damp White House lawn and sat with some staffers from the Egyptian embassy. We were there to witness the signing of the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty after long talks between the parties at Blair House, the Madison Hotel, back at Camp David and in Egypt.

This was the high-water mark of Middle East peacemaking—and my diplomatic career—to that point. Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin (and later Jimmy Carter) were awarded Nobel Peace prizes. Sadat was killed three years later; and Begin fell into the Lebanon trap, lost his beloved Aliza and died in 1992.

That same year I would stand in the backyard of the residence of our ambassador to Israel for the Fourth of July event, winding up my second tour as a U.S. Foreign Service officer.

The Persian Gulf War had been won the year before, and the Labor Party had just beaten Likud. I found myself standing between the victors, Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Shimon Peres and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, to whom I offered congratulations and best of luck for the future. They and President Bill Clinton would give it their best.

A quarter century later, the Middle East is still in turmoil, and the Palestinians are still waiting for their freedom. But at least major warfare between Israel and Egypt has been rendered obsolete, and waging peace was shown to be possible for a bright, shining moment on a mountaintop in Maryland 40 years ago.