Women Who Make a Difference: Reflections of a Foreign Service Wife in 1982

A Foreign Service spouse reflects on her experiences during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, when struggles for independence from colonial rule exploded throughout the developing world.

BY PATRICIA B. NORLAND

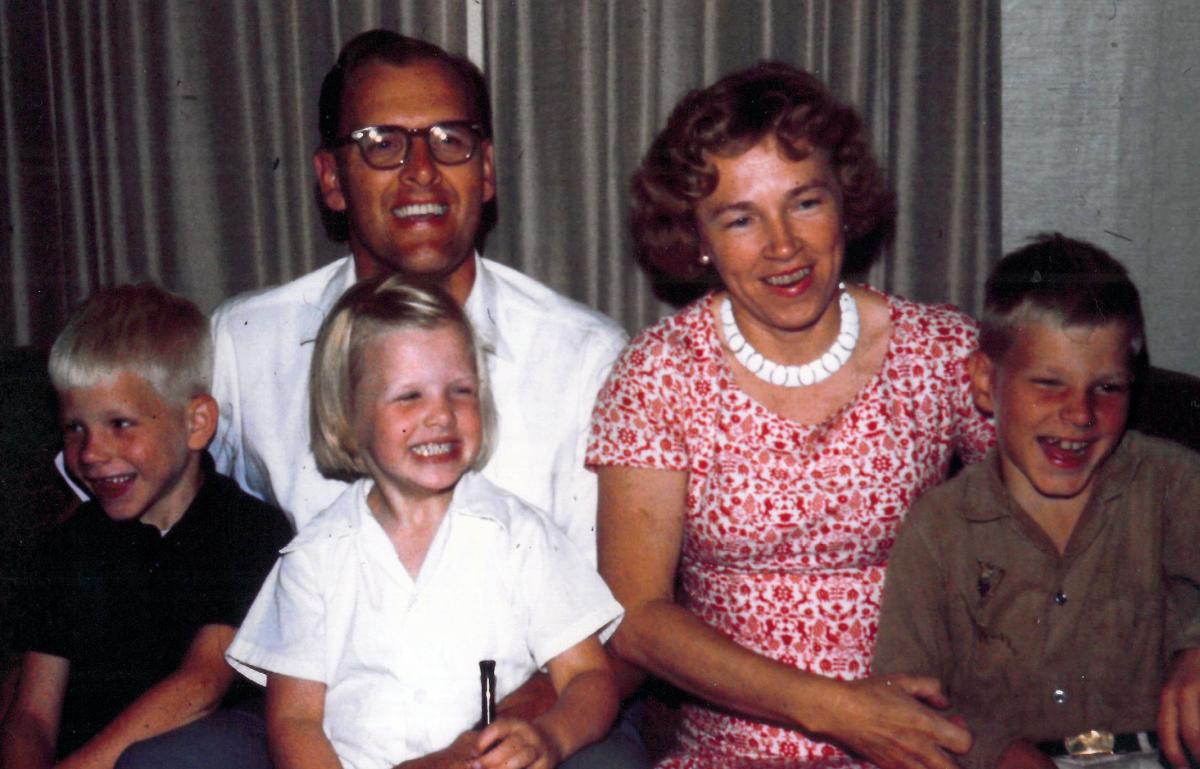

Mrs. Norland, husband Donald, and children (L to R) David, Kit and Richard, soon after arriving in the Netherlands in 1965.

Courtesy of Kit Norland

The life of a Foreign Service spouse offers one of the more interesting and rewarding pursuits—not without moments of sheer horror to be sure, but satisfying and raptly absorbing.

That remains true today, in 1982, as the Foreign Service undergoes a period of strain and change. Salaries, never excessive, have fallen behind in the upper grades; and, as always, many choice diplomatic posts go to non-career appointees. Faced with this prospect, a number of good officers in their middle years are reassessing their onward opportunities and the advisability of remaining indefinitely among the “genteel poor” as school tuition and other expenses mount.

For wives, in particular, Foreign Service life presents new problems. Most young wives now are interested in careers of their own, both for their personal satisfaction and, increasingly, to supplement the family income. However, pursuing a career in law or biochemistry in Ouagadougou is not a simple matter.

Moreover, some young wives are not interested in—or do not have time for—the social aspects of diplomatic life: the entertaining or the philanthropic projects which have long been considered valuable contributions to the U.S. image abroad. The question has even been tentatively broached as to whether the diplomatic social round is any longer truly effective.

Perhaps the most dramatic change of all is in the physical danger that now lurks in many a foreign assignment; in the modern world, diplomats and their families are on the firing line. Few will soon forget the national trauma of the seizure of American hostages in Iran. During these years of change and upheaval abroad, hundreds of Americans have been evacuated from besieged embassies, and the list of U.S. diplomats killed in the line of duty is still growing: Ambassador Cleo Noel and his deputy, Curt Moore, in Khartoum; Ambassador Frank Meloy in Lebanon; Ambassador Adolf “Spike” Dubs in Afghanistan; and others in our far-flung missions.

Young Foreign Service officers and their spouses are apparently thinking twice about serving in these areas, as well they might. The very value of the Foreign Service itself is being questioned: Would skeleton staffs and electronic diplomacy suffice?

Congress has offered some relief for the problems of career, safety and family in the Foreign Service Act of 1980.

Now for the Good News

Fortunately, there also seems to exist a rather firm belief that America will have ever greater need for effective diplomacy and a talented Foreign Service. And Congress has offered some relief for the problems of career, safety and family in the Foreign Service Act of 1980. In such projects as the Family Liaison Office, with its many branches in embassies, the State Department continues to seek solutions for the unique problems confronting its diplomats. And on the sidelines but vociferous, the American Foreign Service Association and Diplomatic and Consular Officers, Retired (DACOR), maintain a vigilant and effective stance.

It is also encouraging to note that the numbers of persons taking the Foreign Service entrance exams are in the thousands and increasing every year. And statistics seem to indicate that, for all her independence, the Foreign Service wife, with family, is still accompanying her husband abroad approximately 90 percent of the time. Thus, it seems improbable that the Foreign Service is expiring; more likely, it is, as usual, evolving.

Since our first assignment in Morocco in 1952, changes have occurred more rapidly than ever in the Foreign Service way of life. From the beginning, one of the most appealing moments to me came when all the preparations for departure to a new assignment were complete and the front door closed behind us for the last time—a moment we were to experience some 14 times in all. Then sweet relief replaced fatigue. The difficult part was over; the great adventure lay ahead.

First came the initial stage of the trip, usually to pier side, along which lay the S.S. United States (the swiftest), the Constitution or Independence (the most cruise-like) or the America (the most fun). A Foreign Service friend has long contended that there are only two ways to travel: “First-class and with children.” The S.S. America came closest to combining the two. Unfortunately, these floating hotels have sailed away forever, and Foreign Service families must now fly on U.S. airlines, except in rare circumstances.

The problems in being children abroad seemed far more awesome in the 1950s than now. Ever since our daughter, Kit, was born in a small, reasonably immaculate French clinic in Abidjan, my own conception of health conditions in foreign countries has become more realistic.

It was not the difference in weather between north and south, but the political climate that had the deepest influence on our lives and lent great interest to the years we spent in Africa.

The logistics of raising a family abroad have nevertheless increased in complexity. Where an international or American school or other accredited form of education is not available, the biggest wrench comes when the Foreign Service child must leave the family circle for school, usually in the United States. The British have long since adjusted to this problem as, seemingly without a tremor, they send their young ones off as early as the age of 8. For most Americans, there are sleepless nights and many sinking sensations. The problems of school, travel, friends, vacations, jobs, medications and other considerations for Foreign Service children are all real, and the Family Liaison Office has an important role to play.

But distinct advantages for children in Foreign Service life remain: new languages, friends of all nationalities and visits to such far-off places as the lagoons of the Seychelles, the high Atlas, the canals of Friesland and the incomparable Okavango. And there is also the opportunity to live in different cultures, not as a tourist but as a privileged resident. The latter is not something to dwell upon. One can only hope the family, both parents and children, will live up to and enhance the image of the nation that has sent them abroad.

As for the Foreign Service wife herself, the diplomatic life can offer infinite rewards: good friends (both foreign and from the embassy “family” itself), theater, shops, travel and, of course, a variety of excellent cuisines. While a recent symposium has concluded that “the role of the husband depends in no small part upon the wife,” much also depends on her husband’s position on the career ladder and where they reside.

From Africa to Europe, and Back

Our itinerary has taken us all over Africa and Europe, two continents offering distinctly different lifestyles. While in the northern European sphere, the procession of social events continued apace; the great surprise to me was to fall, as Americans seem to do, under the spell of history. In Paris we occupied part of an 18th-century country house, three blocks from Marie Antoinette’s “Hameau de la Reine” in the park of Versailles. Later, during our five years in the Netherlands, we wandered along the cobblestone streets where the Pilgrims lived before setting sail; it was unexpectedly moving to hear the American ambassador speak on each Thanksgiving Day in the church where the Pilgrims worshipped. The days were filled with much activity, but living in Europe made it possible to observe up close its weathered bones and to look into the shadows of its history.

By contrast, in Africa, history was being made in the full glare of a hot sun. It was not the difference in weather between north and south, but the political climate that had the deepest influence on our lives and lent great interest to the years we spent there. This was the era of the African struggle for independence; between 1952 and my husband’s retirement in 1981, the Third World literally exploded. During this period, 50 new nations were delineated on the map of Africa.

Patricia Norland, seated at center, joins daughter Kit, second from right, and Vietnamese-language teachers for the Tet festivities at the Foreign Service Institute in February 2007.

Courtesy of Kit Norland

Our introduction to this powerful force came in Morocco, our first post and among the first African countries to gain independence. When we arrived, the French masters of the country were in the process of exiling the popular Sultan Mohammed V to Madagascar. Three years later, before leaving, the most violent uprisings and massacres by the local populace took place outside the capital, Rabat. But it was possible one sunny day to wheel our first baby to the cliff overlooking the Bou-Regreg River and witness the triumphant return of Mohammed V to independent Morocco where his son, King Hassan, now reigns.

In the Ivory Coast (now Cote d'Ivoire), the political climate was quite different. Here, President Felix Houphouet-Boigny had chosen the path of conciliation with France and development of his country. Our first Fourth of July reception was a milestone. The usual heavy pall of heat had descended on the afternoon, and it was necessary to prepare the hors d’oeuvres for 200 guests with only one small refrigerator to keep things cool. But it was well worth the effort when the president himself came to the reception—a rare honor and a signal that he wished to undertake friendly relations with the United States.

Our first close brush with violence came later, in Guinea, where President Sekou Toure, a supposed Marxist who has nevertheless proved to be his own man, had chosen independence from the French community. Here, during a surprise attack on Nov. 22, 1970, by a small invading flotilla, apparently from Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau), we found ourselves, throughout an entire night, stretched flat on the floor in the company of some equally prone members of the staff and Peace Corps, as bullets flashed past the windows and across the garden into the palm trees. The months of terror that followed were worse than the invasion. Except for diplomats, who were presumably immune to arrest, the residents of Guinea could not be certain who would end up in the sinister Camp Boiro Prison. It is to be hoped that Pres. Toure’s current efforts to develop this potentially rich country with Western aid will yet bring benefits to a patient and gifted population.

In March 1980, five months after our arrival in N’Djamena, civil war again broke out in the dead of night, with great ferocity.

Fond Memories

A happier meeting came in 1976 when my husband became ambassador to three very beautiful countries in southern Africa: Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. We found three independent countries, nurtured in the English parliamentary tradition and devoting their energies to the modernization process. In this they were abetted by a large and dedicated expatriate staff of experts from Europe, the United States (with extensive U.S. Agency for International Development programs), China and elsewhere, and by surprisingly generous grants of aid from Scandinavian countries. Everyone, it seemed, wished to help, and the resulting spirit of cooperation and energetic drive reminded one of the frontier days of America.

From these relatively peaceful lands, the wartorn country of Chad—our next and last assignment—brought us again into the vortex of evolving Africa. After the struggle for independence and a long civil war, the country was now poverty-stricken and unstable. Hundreds of uniformed African soldiers on the streets, all bearing Kalishnikov rifles, underscored a deep sense of foreboding felt throughout the country.

In March 1980, five months after our arrival in N’Djamena, civil war again broke out in the dead of night, with great ferocity. Members of the embassy staff, unable to leave their homes, hastily erected barriers of furniture and mattresses, while machine guns were fired from positions in their gardens and mortar rounds fell indiscriminately. Fortunately, foreigners and diplomats were not a target. Three days after the fighting began, a lull made possible an escape by car to the French air base on the edge of the city, with white flags on broomsticks signaling neutral status. All our possessions, with the exception of one handbag each, were left behind.

Those who were evacuated felt inordinately grateful to be alive, but the continuing plight of the Chadians, a kind and gracious people, haunts the memory of all who were there. It was typical of this era that our view as we flew out of the capital was of explosions and mounting plumes of smoke.

The period in which Africa has achieved independence is drawing to a close. On lonely mountain slopes of the countries we came to know and in the dusty villages of the African bush, small health clinics and rural schools are beginning to blossom—albeit, tentatively. Now the battle to survive in the modern world, and to progress, is being waged.

Throughout our time abroad, it was our privilege to know many women who, in one way or another, were in the forefront of the hardships and drama of this period.

Getting Involved in Local Communities

As many a Foreign Service wife has found, the almost unlimited needs of developing countries offer abundant opportunities to participate in the life of the local community. In Botswana, a small, enthusiastic American Women’s Club and the sturdy support of the embassy wives enabled the American community to join effectively in various health, educational and cultural projects, and to undertake some of their own.

Several American wives had full-time positions in the field of health and education that required them to balance domestic life with travels, near and far. One successful project, introduced under American auspices during the ‘Year of the Child,’ was a program whereby pre-school Botswanan children were given a kind of “Sesame Street” glimpse of school life by their first- and second-grade brothers and sisters. The approach has since been incorporated into the Botswanan school system.

Throughout our time abroad, it was our privilege to know many women who, in one way or another, were in the forefront of the hardships and drama of this period. When I think of the overburdened ministers in these emerging countries, the faces of their wives come also to mind: Gladys Masire, wife of Botswana’s vice president; and Lena Mogwe, wife of its peripatetic foreign minister; as well as Mamie Kotsokwane and others in Lesotho and Swaziland.

The memorable times we shared were only a part of the duties they had long been performing: attending graduations and award ceremonies, and participating in activities of the Red Cross, YWCA, Professional Women’s Association and other charitable organizations. There were also the fairs, benefits and bazaars, the military parades of the small defense forces, the official trips and receptions, the celebrations and funerals.

Then, as now, in recalling the remarkable individuals we have known in these young countries, there glimmered through my mind a familiar phrase from the past: Non ministrari sed ministrare (Not to be ministered unto but to minister), Wellesley College’s motto.

Over the years, the women we met and worked with have been fully engaged in encouraging their countrymen to join in moving, for better or worse, into the modern world. Beneath their modesty lie strength and a great willingness to serve. The same, I dare say, is true of Foreign Service spouses, as well.

Read More...

- In Memory: Patricia B. Norland (The Foreign Service Journal, Sept. 2014)

- A “Trailing” Spouse? (The Foreign Service Journal, March 2014)

- Family Liaison Office (state.gov)

- Memoirs of a Foreign Service Officer’s Wife 1938-1958 (The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training)